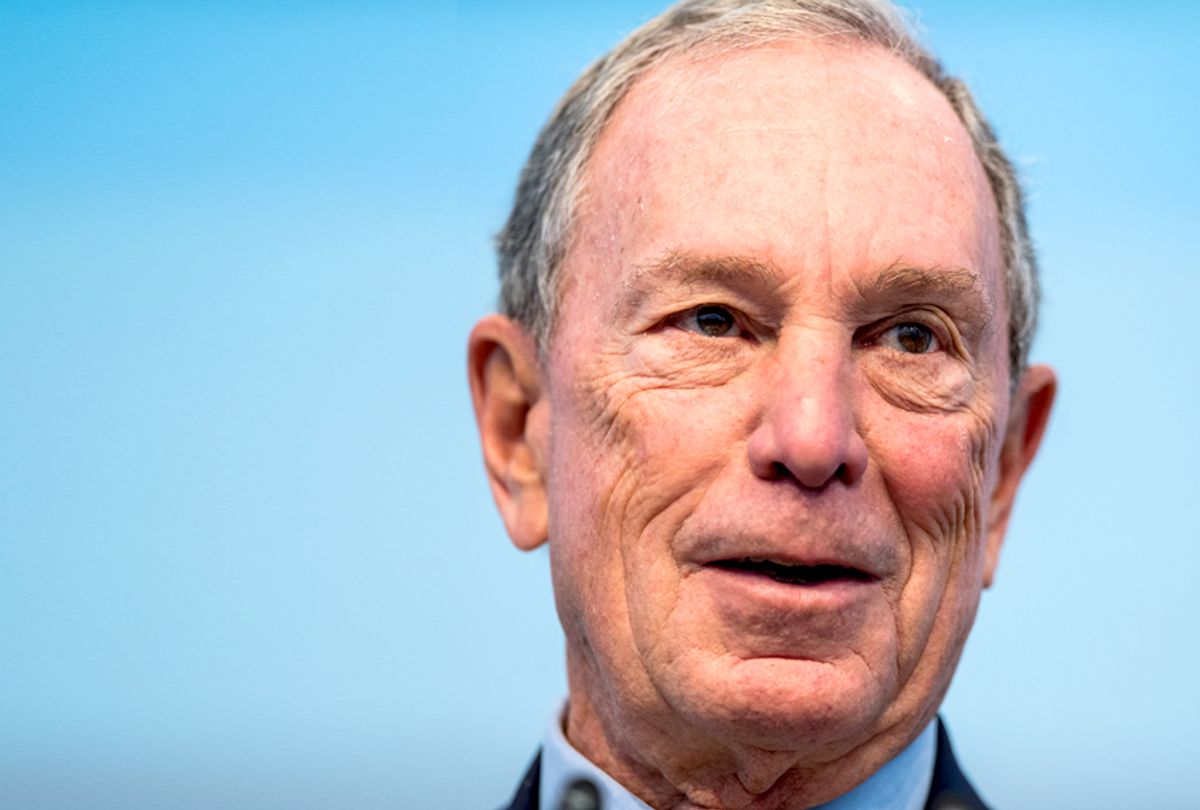

Former New York City Mayor Mike Bloomberg falsely claimed that he had only apologized for the city’s racist stop-and-frisk policy after he announced his presidential bid, because “nobody asked” him about it previously.

Bloomberg apologized for the racist Trump-backed policy he previously championed as soon as he kicked off his Democratic primary bid, even though he publicly defended the policy just earlier this year.

“I was wrong,” he said in a speech to a predominantly black church. “And I am sorry.”

During Bloomberg’s 12-year tenure as mayor, millions of people were stopped and searched by police, because they were determined to be suspicious. In 2011, shortly before a federal judge ruled that the program was unconstitutional, 88 percent of all stops involved people who were black or Latino. Young black and Latino men accounted for more than 41 percent of stops, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, even though they made up less than 5 percent of the city’s population.

“Over time, I’ve come to understand something that I long struggled to admit to myself: I got something important wrong,” Bloomberg told the church. “I got something important really wrong. I didn’t understand back then the full impact that stops were having on the black and Latino communities. I was totally focused on saving lives, but as we know, good intentions aren’t good enough.”

Bloomberg, who has already spent nearly $60 million in less than two weeks to blanket television screens across the country with ads for his campaign, sat down with CBS News’ Gayle King during a campaign trip to Colorado on Friday.

“Some people are suspicious of the timing of your apology,” King told Bloomberg.

“The mark of [an] intelligent, competent person is when they make a mistake, they have the guts to stand up and say, ‘I made a mistake. I’m sorry,’” Bloomberg replied.

“We don’t question your belief that you made a mistake,” King said. "I think the question is the timing that you realized you made the mistake."

“Well, nobody asked me about it until I started running for president, so, c’mon,” Bloomberg falsely claimed to the host.

“Are you saying that you realized that you made a mistake before, but you just didn’t mention it until now?” King pressed.

“I think we were overzealous at the time to do it,” Bloomberg replied, dodging the question. “What was surprising is when we stopped doing it a little bit, we thought crime would go up. It didn’t — it went down.”

“You know — should’ve, would’ve and could’ve — I can’t help that,” he added. “But, in looking back, made a mistake. I’m sorry. I apologize. Let's go fight the NRA and find other ways to stop the murders and incarceration. Those are things that I'm committed to do."

Bloomberg’s false claim is baffling given the years he spent defending the controversial policy even after it became clear that nearly 90 percent of stops targeted people of color. Bloomberg defended the policy in 2012 after thousands of demonstrators marched in opposition to the program, saying it should be “mended, not ended.”

He appeared in a predominantly black church that year to declare that "we are not going to walk away from a strategy that we know saves lives,” even though other major cities saw similar declines in murder rates without utilizing unconstitutional policies.

Bloomberg even defended the policy after it was struck down as unconstitutional in 2013, arguing that it was a “a dangerous decision made by a judge that I think just does not understand how policing works.”

He went on to write an op-ed in The Washington Post titled “Stop and Frisk Keeps New York Safe.”

“The proportion of stops generally reflects our crime numbers does not mean, as the judge wrongly concluded, that the police are engaged in racial profiling,” he wrote. "It means they are stopping people in those communities who fit descriptions of suspects or are engaged in suspicious activity."

Bloomberg even countered criticism that the policy was racist by arguing that, in fact, too many white people had been stopped.

“They just keep saying, 'Oh, it's a disproportionate percentage of a particular ethnic group.' That may be, but it's not a disproportionate percentage of those who witnesses and victims describe as committing the [crime],” he said in a 2013 radio interview. “In that case, incidentally, I think we disproportionately stop whites too much and minorities too little."

Bloomberg even defended the policy earlier this year — just months before his apology.

"We focused on keeping kids from going through the correctional system,” he said in January. “Kids who walked around looking like they might have a gun, remove the gun from their pockets and stop it. The result of that was — over the years, the murder rate in New York City went from 650 a year to 300 a year.”

But as Bloomberg mentioned in his CBS interview, gun crimes continued to decline after the policy was ended. During this same time frame, cities like Dallas, Los Angeles and New Orleans also cut their violent crime rates in half — without using policies like stop-and-frisk.

After Bloomberg’s apology, his successor, Democratic Mayor Bill de Blasio, excoriated the now presidential candidate's sudden turn after his decision to run for president.

“People aren’t stupid,” he told CNN. “They can figure out whether someone is honestly addressing an issue or whether they’re acting out of convenience . . . This is a death bed conversion. We all appealed to him for years to reconsider, and I think it is a statement on him that he was very dismissive.”

Shares