There’s a line in the new Apple TV+ series “Truth Be Told” that I haven’t stopped thinking about since it was spoken by lead character Poppy Parnell (Octavia Spencer): “I’m not a prosecutor, I’m a podcaster.” It’s not meant to be humorous, but it is delivered with such ferocity that you can’t help but cringe and chuckle.

In the series, which is loosely based on the 2017 novel “Are You Sleeping,” Poppy is a retired New York Times reporter who wrote a series of articles about a young teen (played by Aaron Paul) who killed his neighbor. In those articles, she portrayed him as a monster — a sort of snake in the well-manicured, suburban grass — and he was ultimately put away for life. Now, nearly 20 years later, new evidence emerges that makes her rethink her original articles.

Conveniently, she is a true-crime podcaster with a ready-built audience, so she begins recording herself attempting to make sense of the case again. Each week, with the help of a dutiful assistant and an ex-boyfriend who also happens to be an ex-policeman, she releases a new episode detailing what she has found — seemingly without regard for journalistic ethics or proven facts. It’s infuriating and mildly entertaining, and, if it had been a little pointed, could be a nice commentary on the true crime bubble in which we find ourselves.

People have always been interested in true crime, starting with 16th century pamphlets — both sensational and moralistic — about local murders, and rocketing through the 20th century with novels like Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood” and the “serial killer panic” of the ’80s and ’90s. But throughout this decade, we saw a real uptick in people’s hunger for more stories within the genre.

Some of these are formulaic and exploitative — I think of the Oxygen series “Snapped” — while others are a little too hot for the serial killers of yesteryear, like Netflix’s two Ted Bundy projects: “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile” and “Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes.”

But throughout the 2010s, we also saw some true crime projects that broke form in a way that moves beyond grim for grimness’ sake and causes viewers to think about humanity, justice, and power in new, insightful ways.

“Serial” and “The Jinx”

Hosted by investigative journalist and public radio producer Sarah Koenig, “Serial” promised listeners a true crime story given the now-familiar “This American Life” treatment. Every episode began with the show’s understated theme music and a prison phone call greeting. Over the course of the first season, which debuted in 2014, Koening attempted to unravel the case of Hae Min Lee, who was allegedly killed by classmate Adnan Syed.

When the show first started broadcasting, Koening and her team had collected about a year of interviews and material — but they still didn’t know how the season would end. There was still investigation to be done. Through 12 episodes, the “Serial” team brought to light a lot of evidence that was relevant, but inconclusive. Adnan was likable; it was possible he didn’t kill Hae Min. The entire show was like a game of three-way tug-of-war between truth, evidence, and feelings.

What materialized from the first season wasn’t a single groundbreaking revelation that reversed his conviction (he was later denied a Supreme Court appeal for a new trial), but a better understanding of the legal system, investigations and the inherent shortcomings of both.

It also primed viewers and listeners for true crime series that have real-world impacts and consequences — and that straddled, sometimes uncomfortably, the lines between journalism and storytelling — like the 2015 HBO docuseries, “The Jinx,” which was about real estate heir and accused murderer Robert Durst.

That series gained widespread exposure when Durst was arrested on first-degree murder charges for the death of his friend Susan Berman, the day before its finale, which included audio of him on a hot mic rambling to himeself, “What did I do? Killed them all, of course.”

“Making a Murderer”

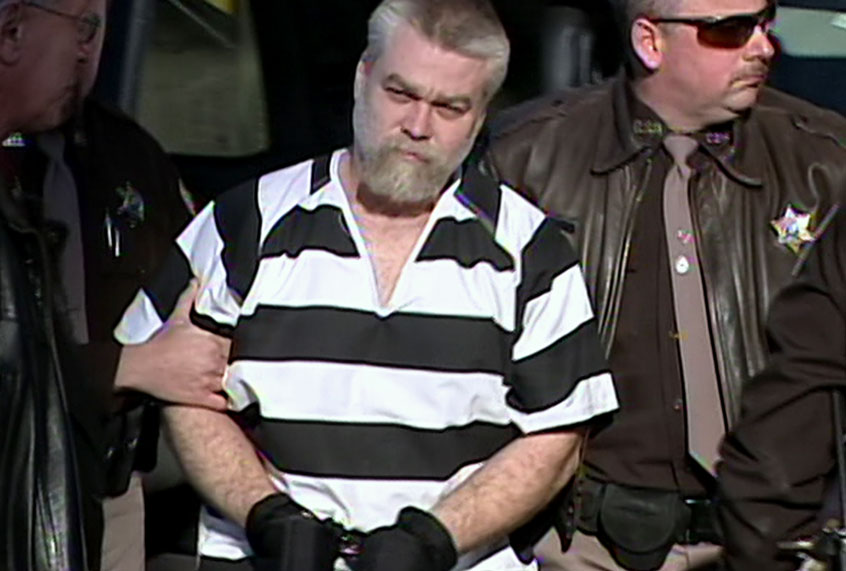

In that same vein, Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” left many of its viewers with questions about the validity of the judgment made in the case of Steven Avery and Brendan Dassey, who are both serving life sentences for the murder of Teresa Halbach.

The series opens by telling the story of how Avery was once already wrongfully convicted; he served 18 years in prison for a sexual assault he didn’t commit, but he was exonerated by DNA evidence in 2003. Two years later — as Avery was in the midst of civil lawsuit against Manitowoc County to recover $36 million dollars in damages for his wrongful conviction — he and Dassey were arrested in connection to Halbach’s murder.

While the Netflix series is not particularly unbiased, it — and Avery’s attorney, Kathleen Zelner — makes a very compelling argument that Avery was framed for the murder, and that Dassey, who was 16 at the time of the arrest, had been coerced into confessing to the crime; compelling enough that thousands of people began advocating in real life for justice to be restored.

Following the release of the show’s first season, 129,841 people signed a petition asking President Barack Obama to pardon Avery and Dassey. While the White House petition went unfulfilled — the president can’t pardon state criminal offenses — a new confession was offered up in September by an unnamed Wisconsin inmate as part of the filming of “Making a Conviction,” an upcoming docuseries by director Shawn Rech.

“The Keepers”

Another groundbreaking docuseries that saw real-world ramifications after its release was “The Keepers,” a seven-part series about the 1969 disappearance and murder of Sister Cathy Cesnik, a young nun in Baltimore.

As described by Salon’s Erin Keane, her “story remains entwined with that of explosive allegations of sexual abuse at the Baltimore Catholic high school where she taught. The murder case was never solved, but the narrative of the show returns again and again to Father A. Joseph Maskell, a priest accused of raping and sexually abusing dozens of girls during his brief time as chaplain and counselor at Archbishop Keough High School.”

After filming of “The Keepers” had concluded in 2017, police exhumed the body of Father Maskell; the DNA from the body did not match the crime scene evidence, meaning the investigation had hit another dead-end.

“Mommy Dead and Dearest”

Erin Lee Carr was one of my favorite true crime documentary filmmakers to emerge this decade. She is a master of dissecting stories primed for sensationalism, pulling at the dominant narratives — which are often those easiest to tell and consume, built as they are on familiar tropes and formulas — and also, our collective hunger for them.

Carr’s 2015 documentary, “Thought Crimes: The Case Of The Cannibal Cop,” dug into the case of Gilberto Valle, an ex-NYPD cop who was convicted of conspiracy to kidnap after his wife found that Valle had spent time detailing plans to kidnap, rape, and cannibalize several women on a number of fetish websites. Her 2019 documentary “I Love You, Now Die” delved into the death of Conrad Roy, who was prompted via text by his girlfriend, Michelle Carter, to kill himself.

But one of her most compelling documentaries of the 2010s was “Mommy Dead and Dearest.” Released in 2017 on HBO (and following Michelle Dean’s Buzzfeed article on the subject), the film uses home videos, text messages, medical records, and interviews to piece together the death of Dee Dee Blanchard at the hands of her daughter Gypsy Rose Blanchard and Gypsy’s boyfriend Nicholas Godejohn.

While many media outlets focused on the fact that Gypsy had lied about her ability to walk and demonized her, Carr really dug into the abuse Gypsy had suffered at the hands of her mother, including years of being lied to about the state of her health and being fitted with unnecessary feeding tubes; as Carr reveals, Gypsy was a victim of a victim of Munchausen syndrome by proxy. The result is a study in how true crime filmmakers should look beyond the headlines.

“Don’t F**k With Cats”

This new Netflix documentary, released on Dec. 18, has all the makings of a good true crime series: intrigue, plot twists, a compelling villain and a story that is considerably deeper than the initial premise. It begins with an internet truth universally known: you don’t f**k with cats.

When videos are uploaded of a young man torturing and killing kittens, a group of online cat lovers-turned-vigilante investigators make it their mission to hunt him down. What they reveal, and the international manhunt that ensues, is more shocking than they ever could have anticipated.

As I wrote in my review of the series, “Don’t F**k with Cats,” which is comprised of three hourlong episodes, is expertly paced. Unlike many true crime series which are told in past tense, a narrative structure that sometimes lends itself to a sense premature resolve, this series is told in future tense. It buzzes with this anticipatory energy; every discovery the internet sleuths make, you feel you’ve uncovered with them. Every new horror that is revealed, you feel in your gut.”

While it has one narrative snag, the craft showcased in the editing of “Don’t F**K with Cats” makes it a series worth ending the decade on.