It will not come via owl post or carry any special engraving, but sooner or later, your son will get his invitation to Dick School. Maybe you remember the day your own arrived. It is, for the American male, that moment when you learn that there is only one limited ideal of what it means to be a real man. It's the moment you are educated that boys don't cry or that feelings are for girls or the way you dance is weird.

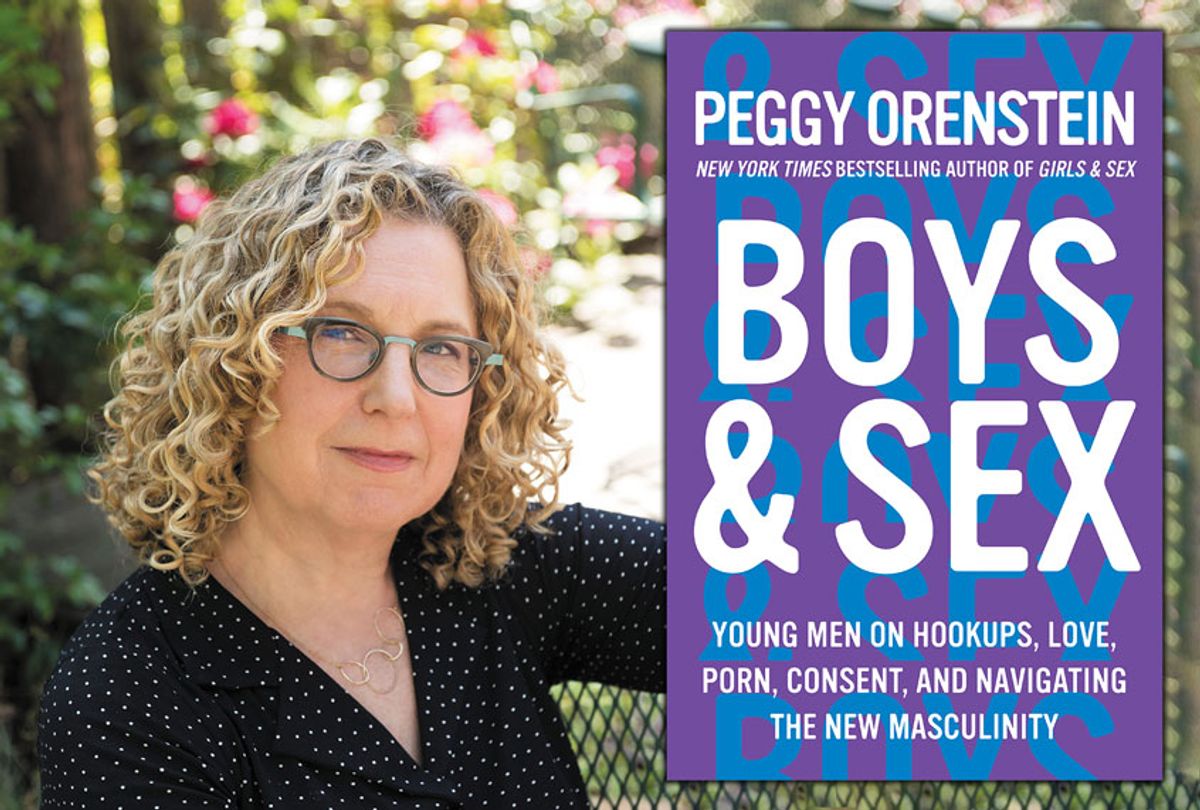

Peggy Orenstein's invitation to Dick School was a very long time in coming. For over 25 years, she's been chronicling the lives of girls, through her bestselling books like "Schoolgirls," "Cinderella Ate My Daughter" and "Girls & Sex." But in her latest work, she trains her expert eye on the world of adolescent boys, and the unique set of challenges that young men are facing today. "Boys & Sex: Young Men on Hookups, Love, Porn, Consent, and Navigating the New Masculinity" is not just a candid and often devastating view into the lives of real high school and college boys right now; it's an affirmation of hope, and an exercise in the power of listening. Our boys have a lot to say, and they need as much help as possible in finding alternatives to Dick School.

Salon spoke recently to Orenstein via phone about her new book, and the secrets boys told her that "pierced my heart."

I'm so glad that you decided to do this pivot to talking about boys, because they're integral to the conversation and they really are so not a part of it.

What I realized very early on was that we have been talking to girls for . . . 25 years. It's really time to bring boys into the conversation, because nobody is talking to them. Nobody is listening to them, to hear how they're thinking about all these issues that are so crucial, not only at this historical moment, but in our lives for our wellbeing around sex and relationships and gender dynamics. What could be more important to our lifelong happiness than our relationships and our ability to navigate them and understand them?

What was it that persuaded you that this was the book that you were going to write next? You are an expert on girls.

Didn't want it to. Totally didn't want to. I really never thought I would write about boys. That was not on my to-do list. But after the girl book, pretty much everywhere I went, people said, "When are you going to write about boys? My initial response was, that was somebody else's terrain. It wasn't mine. I had been in the trenches of adolescent sexuality for about five years at that point. I did know the landscape. I did know the basic dynamics of it. I had that. I started thinking about it, and then #MeToo came along and suddenly, the sheer breadth of misconduct across every sector of society became glaringly apparent.

It became clear that we had an imperative to reduce sexual violence. It also felt to me, on the upside, like an opportunity to engage boys in these crucial conversations about sex and emotional intimacy and gender in a way that we never have. It actually created this little crack in the edifice that allowed me to squeeze in and say, "You know what? Actually, people are interested. Parents want to think about how to raise boys differently. Boys want to think about how they can have a more expanded view of masculinity and not do harm and be the mutually gratifying partner that they want to be."

And if it's only women engaging in the conversation and doing the emotional labor of defining how we're going to move forward as a culture in terms sex, intimacy and relationships, that's a problem.

It's definitely true that as I've been starting to speak, the audience is a lot of women. But there are men there, and I have been trying hard to talk about fathers and male role models as a really important aspect of raising better guys. I think that a lot of times men think that if they aren't perfect, if they aren't perfect in their relationships, if they don't know exactly what to say or how to say it, that they just don't do it. That they just default to silence.

The boys [I interviewed] were so clear that they wanted to hear from the men in their lives, not only about sex, but about the emotional side of sex. They wanted to hear about their fathers' regrets and talk that through in terms of what was going on with them. I feel adult men need to know, you don't have to have all the answers and you don't have to have the perfect relationship yourself. Maybe you're not that great at talking to your own partner. Certainly your own dad didn't talk to you. That's probably for sure. But if we can take that leap — I was hoping that the book would help with that — it would be a tool for parents, a tool that dads would read too. Then boys could read it and maybe think about how to open up a more meaningful dialogue with their peers, or even just in their own heads.

One of the saddest things in the book to me was the boy whose dad finds his porn. The boy says, "Well, I know what's in your bookmarks." And that's the end of the conversation.

He had snooped on his dad's computer. [The dad] just said, "You shouldn't be looking at that," and sat down and started watching TV. The boy said to me, "I felt really let down by that." Even if [the dad] had said, "Yeah, but watching this is not going to do you any favors in terms of your own sex life." Or if he just said a few more things to him, it would have been so helpful. That was really poignant.

Again and again, what comes up in the book is what you call the invitation to Dick School, and how pervasive that is and how hard it is. Girls are sharing information. They're not necessarily gaining any fantastic insights, but boys are not checking themselves against each other in a very deep, emotional way. They're not calling each other out, because there is a price that you pay. If you do speak up, you can lose your social credibility.

That's something that we really have to work on and talk about with boys, because a lot of them want to say something when they were in those locker room situations. [One interviewee,] Cole, said there was a guy who was saying something just despicable about girls. He and a friend tried to speak up, and they got mocked. Cole shut down, but his friend kept trying every time, and he lost all his social capital. Cole said, "I watched people stop liking him as much. They they didn't pay any attention to him." He said, "I was just sitting there with buckets of social capital, but I wasn't spending it." He was this guy who was very jock in his presentation. He was last guy you would have thought would be really wrestling with these issues.

He said, "I don't want to have to choose between my dignity and my camaraderie with other guys," basically being part of the team. He was going into military service. "But how do I make it so I don't have to choose?" When he said that, he looked at me and he banged himself on the chest. "How do I make it so I don't have to choose?" He looked at me with such agony in his eyes and I thought, "That is really deep." That is really what boys who are standing in that situation are facing. They're teenagers, they don't want to be marginalized. They don't want to be mocked. They don't want to be excluded, and they know what's happening is wrong. It's in that silence, that cutting off of heart and head, that boys learn what it means to be a man.

Let's also say to quadruple all of that if you are a member of the LGBTQ community, if you are a person of color. Your social standing is so precarious in this world anyway, that your social capital is much more vulnerable.

It was always interesting to talk to gay and trans boys about masculinity because gay boys were spies in the house of masculinity. If they were younger and not out and trying to not be targeted, they were conscious of how they walked. They were conscious of how they stood. They were conscious of their voice. One boy said to me, "I practice my 'I'm the shit' face in the mirror, my bro face." Then he said, "I slipped up once at the first middle school dance. I was dancing and some other boy came up and said, 'You move your hips too much, like a girl.'" He said it was so devastating, because it was something he was inclined to do naturally, and it was a tell. Then he would just watch other boys dance and just dance like they did. And he lived in the Bay area. This was not a guy who lived in some enclave that you think of this as being threatening to gay kids.

My daughter goes to a progressive high school downtown that could not be more full of kids of all different orientations and gender expressions, and yet there is still that "no homo."

Today the world has changed, obviously, and straight guys have gay male friends and they may even have trans friends or non binary friends. When they talked about the use of "fag" or "no homo," they would say, "Oh my God, I would never say that to an actual gay person." Like somehow that made it okay. I thought, okay, that's a contradiction, let's explore. It was more about policing masculinity and reinforcing emotional suppression in particular.

Especially "no homo." C.J. Pascoe, whom I adore, is a sociologist in Oregon. She did a survey of how the hashtag #nohomo was used on Twitter. She found that it was used as not just a homophobic slur, but as a shield that allowed guys to express really normal human emotions like affection or joy. So they could say, "I miss you. We should hang out soon, no homo." Because they're not allowed to do that. There was so much about talking to the boys that pierced my heart. I know what it's like to be allowed the full range of emotion, and I know what they're not able to do and I know that they're not able to express.

When we would talk about crying or about sadness or what happens when you break up with a partner and the inability to talk to anybody about it, they say, "I trained myself not to feel." Or, "I built a wall." Or, "We confide in nobody." It's really all about vulnerability, right? It was this constant wrestling with vulnerability and avoiding it and denying it or making a decision to capitulate to it. We know that vulnerability is crucial to human relationships. So it on one hand it undermines their ability to have mutually gratifying relationships, and on the other end, it can harden them and make them lose compassion and empathy and pave the way for misconduct.

You're reminding me of that anecdote from your book about the boy whose girlfriend had been cheating on him. He broke up with her, but she was the one person he would have been able to talk to about all of the pain and the suffering that he was going through.

His girlfriend was his emotional support. Then she cheated on him. What do you do? He snapped his fingers and said, "She cheated on me, so I just forgot about her." In fact, he spiraled into depression and he couldn't do his schoolwork. Everything that had been a source of happiness for him was no longer a source of happiness. His grades dropped. He was trying to white-knuckle it because he felt as a guy he shouldn't be, as he put it, "a little bitch." Finally he had sort of a breakdown in front of his mom.

I think it feels very good to mothers of boys when their son confides in them, when their son shows that emotional vulnerability with them. Obviously it's very sweet and makes you feel connected, but if we process boys' emotions for them rather than helping them learn to process them themselves, we're teaching them over and over that women are the the source of their emotional labor. That is really not going to serve them when they get into relationships, as we as adult women are very well aware.

This is actually one of the most important points in this book in terms of female readers. [We] want to take care of our boys — understandably, they are our children — but the way that the gender dynamics play out and the way that we end up subtly or tacitly encouraging them to be dependent on us for that emotional processing sets them up to become in relationships exactly what frustrates us in our own relationships. Then the cycle continues.

You spend a lot of time and care talking about the fact that consent is an issue for boys as well. That boys have a right to pleasure, that boys have a right to consent, that boys can feel rejected.

And that they can say no. They can say no. That's the thing, boys feel like they're not supposed to say no. That it makes them less of a man. Girls think that boys would never say no.

There is a difference in that in terms of high school, college-age peers, girls in those situations talk about a feeling of physical powerlessness. Fear is not there for boys. But the experience of unwanted sex for boys could be really painful.

I had a couple boys who talked to me, usually about the first time with intercourse. They had wanted their first time to be with somebody that they cared about and certainly somebody where they were aware it was happening and weren't drunk beyond being able to move. They were really upset, and they reacted very much the way we know that girls do and understand that girls do. They would spiral out of control, do badly on their school work, get depressed, become afraid of further interaction with a partner, not have anybody to talk to. Sexual agency for boys means that they have the right to be able to say no. That they have the right to engage in a conversation about consent, Just full stop. But also, if you are not allowed to say no, I don't know that you can hear it.

If you are raised that you can't say no, how can you understand what the boundaries are? Again and again in this book, you find these boys who are deeply confused.

There's a lot of confusion. That's why I just wanted to make it really clear, hoping that the book would be for parents and boys, but also just among themselves. I feel in a lot of ways that we are with boys where we were with girls when I first started writing about them 25 years ago, when we first started saying, "Hey, something is not right in Girlville."

We have all these new expectations and we think that everything's fine, fine, fine. But in fact, the old [expectations] are just dragging along with them, and it's causing all this conflict and contradiction and some real damage and harm. We have, as parents and activists and advocates of girls, built a whole edifice to help support girls — to help them with media literacy, to help them with body image, to help them be able to resist messages, to help them stand up, to help them have the opportunities they deserve in every realm of life and the opportunities to express themselves. While in a way guys have had that upper hand since time immemorial, there is also a way that we want something better and different for them. It is time to bring them into that conversation and to help that happen.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Shares