It’s no stretch to say that David Talbot has been a towering presence in media for the past 25 years, though regular Salon readers may be biased given that he started the online magazine. Besides his hand in Salon’s history, Talbot has written New York Times bestsellers like “Brothers,” “The Devil’s Chessboard,” and “Season of the Witch,” all books that challenged the mainstream media’s narrative on historical events like the counterculture history of San Francisco and the early history of the CIA.

Like any good investigative journalist, Talbot made his mark on American history by extracting what other historians might have missed, rereading primary sources and recasting what was hidden in shadows. While that passion appears through his writing, Talbot has rarely turned the pen back on himself — until now.

In November 2017, Talbot suffered a stroke. The experience was formative, both existentially and politically, as Talbot witnessed firsthand the bureaucratic mess that defines America’s healthcare system.

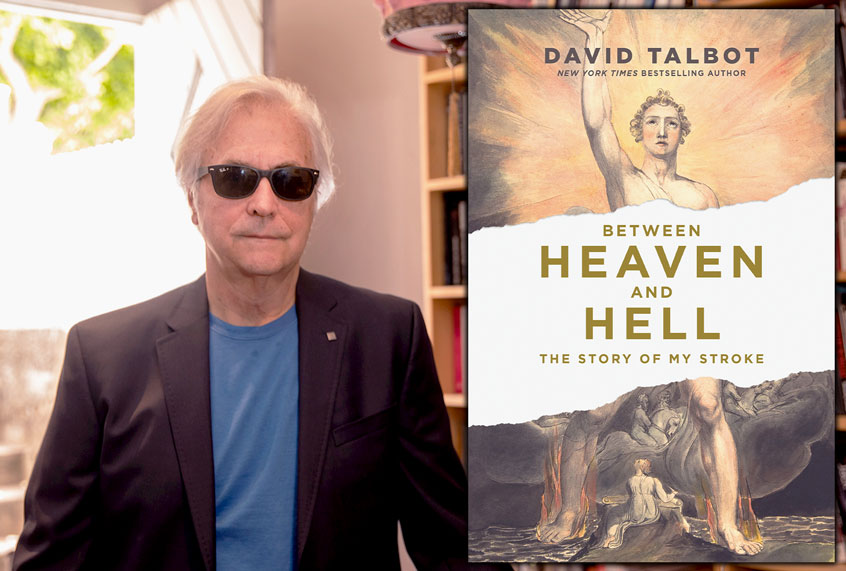

During his recovery, Talbot published short missives about his experience on Facebook. Those eventually (inevitably?) morphed into his newest book, titled “Between Heaven and Hell: The Story of My Stroke.”

Those familiar with Talbot’s writing will notice a shift in his tone. His humor, while still laugh-out loud funny, is a bit toned-down. Talbot tells me that his priorities on life, and what fulfills him, changed after his stroke, too.

We sat down with Talbot to talk more about his book, which hit bookstore shelves this week. As always, this interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

First, I wanted to just ask about how has it been different writing about your life in such a personal way.

It was a big departure for me to write so self-reflectively and not be writing about big historical subjects, or political subjects. And I only could have done it because I had this medical trauma. It became a kind of therapy for me. I’d originally started on Facebook where I’m pretty active, although I’m trying to leave. Hell, we can talk about that later.

But I felt I had to actually [go to] physical therapy . . . because I couldn’t write. Every other word I typed had to be corrected. My hand was like, as I say, a claw. I was paralyzed. I’m semi-paralyzed on my right side. I couldn’t touch type anymore. I still can’t touch type. I just kind of hunt and peck now. And I started consciously writing it as a book at that point. And I’d say most of the book, then, is written for [the] book — not just [for] therapy on Facebook. But I needed to be completely shaken from my old life before I could even think about writing personally in this way.

It was partly to see if I could still type again. But more importantly, if I could still think and communicate. And so it was the first great hurdle for me to know that I could have a life still, other than as an invalid.

And a lot of the book is about how you died and you came back to life. The stroke ushered in a “new you.”

Yes.

I thought it was really interesting how the new you became more curious about quotidian life things. Like — as you mentioned in the book — grocery shopping. Whereas your old mind was more occupied with historical events. I’m wondering how this new curiosity influenced your writing process?

I was much more driven by deadlines. By journalistic cycles. Fundraising cycles. When I was running Salon, my life was all about obligation and compulsion and being an alpha male and trying to control my universe more and more. And I felt that what we were doing with Salon was really, I think, trying to take back journalism from the media and from the corporate establishment. And so it was a huge undertaking. And I felt not just driven by business needs to keep Salon alive, but also to make a point. That journalism could stand for the truth and defy convention.

And I loved it that we started here in San Francisco for that reason. New York was very shocked by Salon in the early years. And after I left Salon, it became just as important to me to rewrite American history. I was writing revisionist history. And writing about the Kennedy presidency and the CIA and so forth. And about the history of San Francisco going through all its turbulent history from the 60s and 70s. I felt these stories weren’t being told right. The narrative was being deformed by people who had a stake in the status quo.

So I felt under a lot of pressure too to start making an argument and to convince people that my version of American history was correct. Now I was liberated after my stroke. I thought, I had nothing to really prove anymore. I felt at that point, I could have died because I had done everything I needed to do in my life professionally. I started Salon and ran it for 10 years. I had written three or four books that I felt really did challenge the orthodoxy about America.

And at that point, I’d say I was in a midlife doldrums when the stroke hit. My one last challenge was trying to convert my writing into screenplays and into either films or TV shows. I was broken by Hollywood. I had my stroke in the middle of it, and I don’t want to blame it all on Hollywood. I kind of facetiously say, “Hollywood gave me a stroke” in the book . . . . but it kinda did.

And after that, I was reduced to being in my home with my dog and not being able to really drive anymore, or go out in the world. I felt very isolated. And yet, I had this need. It was more or less a political need at that point, or even financial need [more] than a personal, psychological need to try to make sense of my life and to make sense of this weird, brief existence that we all have.

I had thought a lot of life and death in the past because I had an older father and I was always afraid he was going to die. I was anorexic as a kid. I had these weird experiences that made me think about mortality. But never in the obviously sustained and deeper way that I did after my stroke. So that opened up a whole new realm for me to write about. I didn’t want to write just about myself though and my own suffering. I wanted to connect it to some other issues about medical care in America and the mixed medical care I received.

And to just explore existential questions about life and death that I knew all people, particularly people my age, in my age group and my generation are facing now. And Ram Dass actually is someone I looked to as quite for some inspiration, some guidance. He was kind of a guru of my generation. He had had a stroke at the same age. So I devoured his book. And then he just died recently.

Yes, that was recent.

I also write about my dog, Brando. I’m not an animal nut or anything, he’s the only dog I’ve had since I was a kid. But he played a huge role as I’m writing the book in welcoming me back home — making me feel at home — and then never leaving my side. Always being this partner.

I felt really lonely a lot after the book. I had been a very busy guy and had people around me all the time. And suddenly, I was very much alone. Which is also a writerly thing. I was forced to become more writerly by being alone, and Brando [was] my only companion.

He just died. He died the day after Christmas.

Oh, I’m so sorry.

It was really actually more traumatic for me, in some ways, than my own stroke. I thought he was going to be my life partner until my last days, but he went before me. And it was quick and sudden. It was strange. So anyway. I’ve had other friends who’ve died, some of serious illness, since I had my stroke. So it seems suddenly it’s the environment that I’m operating within. And it’s more and more important because we all have this Sword of Damocles hang over us from the moment we’re born.

Yeah.

People as young as you — people even younger — you never know when your time is up. And the stroke taught me how tenuous our existence is. Whatever times remain to me, I do want to leave something behind. And the last thing I really have to leave behind is not my version of America or any of that. It’s my version of what life should mean, or can mean, if you live with more awareness.

Can you speak more about where you find meaning and purpose, and how that has shifted for you now since your stroke?

I actually get more joy from those around me. As I said, I don’t feel I have to prove anything anymore, professionally or politically. I feel I’ve made my contribution. We used to have this thing, Living Obits, in Salon that I started. It was a way to actually evaluate a person’s life before they died, after they lived a full life. And I know that I’ve lived as full a life as I probably could have hoped for. What joy I have now is from watching those around me achieve.

I feel my family is of great interest to me. And I also continue to take a strong interest in politics in San Francisco. I’m going to Chesa Boudin’s inauguration. I worked with him and helped raise money for him. I feel like I can’t change America anymore. I just was playing David Bowie’s song, “I’m Afraid of Americans,” which is the way I feel about the country right now.

But I feel that I have some control still over this city, despite the fact the way San Francisco has been overwhelmed by tech capital in the last five to 10 years. I still feel we have a fighting chance here. And we’re electing some really good people like [new District Attorney] Chesa [Boudin]. So I’d say what occupies me nowadays is my love and interest in other people’s work, particularly my family and my city. And my life stops at really those boundaries, I guess.

Reading the book, it seemed so incongruous that you had the stroke when you were out with friends, enjoying yourself, drinking wine. But starting the book with that moment (and the stroke) really laid the foundation for us to get to know the old you. And then later you see the “new” David. So much of the book is about this “before” and “after” of the self, and the difference. Can you speak about that literacy choice?

I thought that was important, because I’m aware of the literature about suffering and cancer and death and stroke and heart attacks. And I read some of it after my own. But I was never particularly interested in human suffering before that. Because it seemed to be fairly formulaic, those stories.

Right.

You’re not interested in a person’s suffering unless you’re interested in their accomplishments. I did think it was important to include a chapter on Salon. And to also write about how I think my version of the Kennedy assassination will ultimately become the correct one. That was a major challenge for me, to deeply investigation that assassination because — probably for you, like, 9/11 was the trauma that shaped your generation’s lives. The Kennedy assassination, which happened when I was 12 years old, really shaped mine. I wanted to give people backstories on me so they could appreciate the forward story, I guess.

While rebuilding your life after the stroke, it sounds like meditation and activism have both been parts of the healing process. And I’m wondering if after the stroke have you found more motivated to be more active in your community and in politics than you were before?

It was starting to grow before my stroke. But I felt it more intimately afterwards because I felt my boundaries, I would so say, had become, had shrunk. And now my boundaries were my home. The trails I would walk on with my dog up the hill. Because, for one thing, I couldn’t just hop in my car and drive to Point Reyes or which I used to love to do on a whim. I felt more immobile because I can’t drive anymore because my vision’s fucked up. And the city’s kind of scary to me. Because I still feel like I’m in a bit of a shadow land. I don’t feel completely alive is the truth.

I feel like I’m in a weird bell jar, like I say in the book. I’m not alert enough to get behind the wheel of a car. And the city streets are much more jammed now with Uber and Lyft. The city’s a little more overwhelming. So I’m glad I don’t drive, but that does limit me. I am more introspective than ever before. And more involved with the life of my city because I feel, for self-preservation, [that] I have to keep some semblance of San Francisco values so it doesn’t become a totally alien and corporate universe.

It sounds like you have hold on a sense of optimism that San Francisco can still have the spirit that you love so much, that captivated you. Is that true?

I do. And it’s, for me, a lot of it’s electoral politics. Unlike the left, in the old days, at least, I do believe in electoral politics. I believe it’s a great test of your connection to the public. Public opinion, public will. And so, I was very heartened by the last elections in San Francisco. Particularly not just Chesa, but the election of Dean Preston to the Board of Supervisors. Progressives now have a solid majority on the board. That’s a big deal. So London Breed, who I think is part of the problem, is a corporate Democrat. She now has to deal with a very strong, progressive majority on the board. That’s become a bulwark against some of the worst tendencies we have in the city now.

I’m hopeful about the future. I still think it’s a dog fight. You have to fight every election. In between elections. I think the police union and other reactionary forces are coming after Chesa to begin on day one. As I told Chesa, “It’s not enough to get elected anymore. You have to have a movement behind you protecting you every step of the way after you.” And Chesa gets that because he comes out of a family of obviously radical activism. It’s exhausting though. That’s the one thing as someone who’s had a stroke. My chapter about Thomas Merton, I think, is important because there I try to deal with this question of “how do you lead a life of balance?” And without introspection, your activism is often unguided, not deep enough, egotistical. All the things he warned against. America is too much a country of action and not enough thought.

Totally.

I do think I have to find a balance. And there’s some days I have to say no when I am invited to speak somewhere. Or say no when I’m tired. Or I have to go read. I’d rather read now. . . And that’s big for me to say no. I used to always say yes. But if I just sat at home on the other hand, and worked, and typed on Facebook my thoughts about the world, that would be a very uninformed life too. I want to be engaged enough to know what’s happening without being overwhelmed by it.

What makes you feel alive today?

Everyone has this feeling. You wake up in the morning, you’re not quite all there until you have your cup of coffee. You’ve been up for an hour or so. Some people take even longer. I have a friend who doesn’t feel fully awake till noon. And she’s a healthy person. So everyone’s metabolism is different. But I definitely felt until I had my shower, actually. It wasn’t just a cup of coffee. I needed a shower to fully wake up. I never wanted to have meetings at Salon, editorial meetings till 10 a.m. — which is one o’clock, unfortunately, back in New York. Not convenient time for New York. But because I felt I wasn’t totally on then. I felt most people dragging until around 10. I didn’t get into work till 10. I needed that time to gather myself. Now my life is permanently like the early hours.

I always feel dazed and dizzy. I am dizzy. That’s part of having a stroke. I have to work with a cane. Not inside, but when I go outside. I can fall easily because I’m not quite steady. I feel my head is encased in some kind of — like I said, I write about the bell jar. But I definitely feel like halfway here, I would say. Not fully alive. Not like I used to be. Certainly not as combative as I used to be. I can’t go to meetings and hold the floor and give speeches. Although I have to do a lot of public events for my book. So anyway, what makes me feel alive.

Having to be forced into public spaces again. Giving interviews. I’m more public than I have been for a while. I have to say the biggest thrill for me this last year was from Sundance on, seeing the premiere of my son’s film [“The Last Black Man in San Francisco”] at Sundance, where it got a standing ovation in the biggest theater in Park City. Like, I never thought I could even show up at Sundance. It was too icy. I wasn’t strong enough at that point and on a cane just walking around town.

But sitting there and saying, I lived to see my son make this movie. Living to see that. I would have been really pissed if I had died and not enjoyed that. My life has not just been about being a writer or an entrepreneur, it’s been being a father.

# # #

David Talbot’s newest book, titled “Between Heaven and Hell: The Story of My Stroke,” is on sale now from Chronicle Prism books.