The dust still hasn't settled on the major literary controversy surrounding the publishing of Jeanine Cummins' novel "American Dirt," but a new month enters new books into the discussion, and February's bounties are plentiful. To start with, Valeria Luiselli's acclaimed novel about a family road trip unfolding alongside the stories of undocumented and unaccompanied migrant minors, "Lost Children Archive," (Knopf Doubleday) which was named one of the 10 best books of 2019 by the New York Times, would make a splendid recommendation for those looking for a well-researched and heartrending depiction of the one aspect of the border crisis, and is out in paperback this week.

Two prominent witty culture critics have new essay collections out this month. Elle senior writer and "Eric Reads the News" columnist R. Eric Thomas offers up "Here For It: Or, How to Save Your Soul in America" (Feb. 18, Ballantine) a memoir in essays about Ivy League code-switching, going viral, covering the 2016 election, and more. And Daniel Mallory Ortberg, Slate's Dear Prudence advice columnist and co-founder of the dearly departed culture site The Toast, is back with "Something That May Shock and Discredit You" (Feb. 11, Atria Books), a hybrid of incisive cultural criticism and heartfelt rumination on transitioning and queer identity. (Perhaps all we need to say here is there is a chapter titled, "Captain James T. Kirk Is a Beautiful Lesbian and I'm Not Sure Exactly How to Explain That," followed by one titled, "Duckie from Pretty In Pink Is Also a Beautiful Lesbian and I Can Prove It with the Intensity of My Feelings." It kind of sells itself?)

Fans of short stories might find their way to Lidia Yuknavitch's "Verge," (Feb. 4, Riverhead) each of her 20 entries bite-sized and perfect, or to Amber Sparks' "And I Do Not Forgive You," (Feb. 11, Liverlight) for its tart blend of the mythic and contemporary and sharp portrayals of strange girls, twisted fairy tales and new stories for old skeletons. And then there's the striking debut of Peter Kispert with "I Know You Know Who I Am" (Feb. 11, Penguin Books), a fascinating short story collection all about liars and the lying lies they tell. Less about malicious deception and more about the how one slips into dishonesty in relationships and in coming to terms with oneself, the stories reveal through these lies, the truth about us all.

And in a timely confluence, three journalists explore the often hidden sides of addiction in high-achievers in these new memoirs: "Smacked: A Story of White-Collar Ambition, Addiction, and Tragedy" by Eilene Zimmerman (Feb. 4, Random House), blindsided by her husband's secret addiction and sudden drug-related death; "As Needed for Pain," by Dan Peres, formerly of W and Details (February 11, Harper), a portrait of the editor as an addict and of a bygone New York media era; and Erin Khar's "Strung Out: One Last Hit and Other Lies that Nearly Killed Me" (Feb. 25, Park Row Books), whose 15 years of drug abuse began during what looked like a "picture-perfect" childhood.

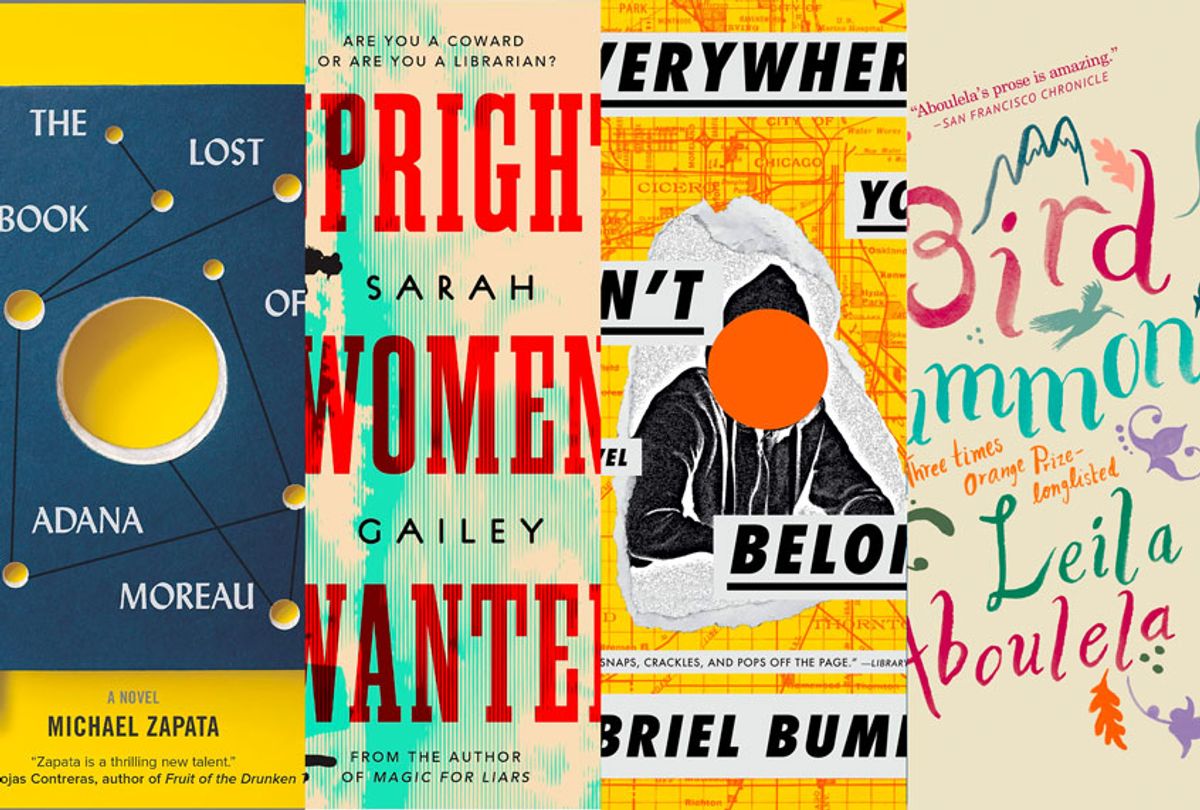

And here are seven books coming out this month Salon staff writers felt were worth a closer look.

"Bird Summons," Leila Aboulela (Black Cat, Feb. 1)

When reading "Bird Summons," I kept imagining a piece of paper with lines of string tied to each corner. The paper represents one's soul, and each string represents a piece of it: family; friends; culture; religion. The strings can support the paper or, if they're pulled too hard, can tear it apart.

The novel, which is touched by magical realism, follows three Muslim women who are on a weeklong trek to visit the grave of Lady Evelyn Cobbold, the first British woman to perform the pilgrimage to Mecca. There's Iman, whose third marriage is disintegrating after being brought to from war-torn Syria to Britain by her second husband. She doesn't feel she's ever had a life independent of being someone's wife.

There's Moni, a wife and mother who gave up her fulfilling career as a banker to care for her son, Adam. He's five and has severe cerebral palsy. Then there's Salma. On the surface, she has it all: a doting Scottish husband, four children, and a successful massage therapy practice; but after her college ex-boyfriend reaches out, she finds herself more and more consumed by thoughts of how her life could have turned out differently — potentially filled with more excitement and thrill?

Once reaching their accommodations, the women are each visited by dreamlike figures who speak to their current fears and pressures, pushing them each towards a place where they can reconcile the women they are (or the women they thought they'd be) with the women they want to be. — Ashlie D. Stevens

* * *

"Everywhere You Don't Belong" by Gabriel Bump (Algonquin Books, Feb. 4)

Growing up in South Shore, Chicago, Claude McKay Love is a young black man whose parents abandoned him and who's been raised on his grandmother's civil rights activism. The riots and protests of 1968 have never been forgotten, passed down as much as any blood-borne legacy. The fear, violence, loss, and defiance he experiences in his neighborhood are far more real than any subjects that are taught in his school.

When a new riot erupts, where the Redbelters have recruited the neighborhood children to help wage a war against the corrupt police terrorizing the streets, Claude has had enough and makes plans to leave Chicago . . . and the only family he's known behind. But can he outrun his problems, his loyalties, his identity? As his grandmother tells him, "The world is no place for a self-hating black boy."

Briskly paced, "Everywhere You Don't Belong" follows Claude from his pre-teen years through young adulthood, and asks how we are raising our children or if we are too caught up in our own cycles to be able to break free. It asks how an individual can truly find autonomy if one doesn't break with the past.

Bump makes his novel debut with hilarious yet ruthless insight. He mixes his observations of the systemic racism and cycle of unrest with the ridiculousness of and unrelenting affection for human nature. There is no time for hand-wringing or self-pity, but even amidst the injustice and fight for survival, there's time for human contact and love. – Hanh Nguyen

* * *

"Upright Women Wanted" by Sarah Gailey (Tor, Feb. 4)

If you're looking for a story in which librarians form a badass defense brigade against fascism — like we aren't already living in one? — Sarah Gailey's slim speculative Western novella, "Upright Women Wanted," will make you stand up in your spurs and whoop.

Like a queer feminist "Deadwood" set in a dystopian near-future of rigidly enforced patriarchal totalitarianism, petroleum and food shortages, and threats of insurrectionist uprisings, Hugo Award-winner Gailey ("River of Teeth," "Magic for Liars") opens with a brutal execution, followed by sheltered Esther getting the hell out of Dodge before she's married off against her will, or worse. She stows away with a group of librarians, hoping to be taken in by the only women allowed to live independently, distributing state-approved reading materials to scattered towns across the Southwest. But Esther finds herself thrust into even more danger — murderous bandits, suspicious officials, her own inexperience, burgeoning feelings for the intriguing apprentice librarian Cye — as the true nature of the librarians' mission slowly comes to light.

At first Esther believes she can find a way to be a compliant woman within the strict bounds of the authoritarian regime — to be safe, to cause no more harm to anyone she loves — and witnessing her slow awakening to a life of unruly and satisfying possibilities is a true delight. "Upright Women Wanted" is both a rollicking adventure and a sincere ode to those who wish to live authentically and without fear, to resist fascism, nurture hope, feed curiosity, and refuse at any cost to buy in to an oppressive system.— Erin Keane

* * *

"The Lost Book of Adana Moreau" by Michael Zapata (Hanover Square Press, Feb. 4)

In 1916, a Dominican girl eludes the U.S. Marines who execute her parents — guerillas in the fight against the American occupation — in the middle of the night. She slips away to Santo Domingo and then to New Orleans with Titus, the self-professed Last Pirate of the New World, and becomes Adana Moreau when they marry. Like his parents, future theoretical physicist Maxwell Moreau has a wandering soul, keeps one eye on the sky. Adana channels her restless imagination into a science fiction masterpiece, "Lost City," a novel of displacement and survival. The Dominicana, as author Michael Zapata dubs her, myth-like, writes a sequel, but on her deathbed destroys the book before it can be published. And yet. In 2005, in Chicago, hotel concierge Saul Drower mails a package to Maxwell Moreau at the request of his dying grandfather. When the box comes back to him undelivered, Saul and his childhood friend Javier, an investigative journalist with an appetite for disaster, decide to fulfill his grandfather's final wish and return Adana Moreau's lost manuscript to her son where it belongs, just as Hurricane Katrina comes roaring to land.

How Maxwell and Saul are connected, and how the mysterious lost manuscript of "A Model Earth" came to be in an elderly Jewish historian's Chicago home to begin with, forms Zapata's elegant and sweeping multigenerational, international story of lives marked by political violence and bound by the shared condition of exile: Lithuania, the Dominican Republic, Argentina, Chile, New Orleans. Our stories are life-threads connecting us to this universe and each other, Zapata's novel argues, and keeping them for each other is one of the highest forms of love. — E.K.

* * *

"The Authenticity Project," Clare Pooley (Viking/Dorman, Feb. 4)

Every now and then, at the coffee shop near my house, a communal notebook is placed out on the countertop — inviting customers to contribute a note, a short story or a doodle. Often, they're pretty superficial, but occasionally when I flip through the pages, a shockingly personal story has been left. Often it's anonymous, but there's an instant sense of connection with whoever was the author.

"The Authenticity Project" takes that feeling and gives it legs over the course of a humorous, fast-paced 370 pages. It begins with Julian Jessop, a 79-year-old British painter who is tired of hiding just how great the loneliness that consumes him is. So he writes about it. In a small green notebook, he details how difficult it is to come home, day after day, to an empty house — which he used to share with his wife — and how he wishes there was a way to share these feelings "not on the internet, but with those real people around you."

He leaves the notebook in Monica's London Cafe, his neighborhood coffee shop, with the hope, though not the expectation, that anyone will read it. That's when Monica, the owner of the shop, discovers it. After reading Julian's confession, she is compelled to make one of her own. She is 38, unmarried, childless and, like Julian, tired of putting on a carefully constructed happy face. Monica writes all of this out and leaves the notebook for another stranger.

This novel has a tremendous amount of heart; it's vulnerable enough to give voice to the loneliness many of us feel in an increasingly digital age (it's a tear-jerker, for sure), but upbeat enough to still be classified as "feel-good." I look forward to the inevitable film adaptation. — ADS

* * *

"Real Life," Brandon Taylor (Riverhead, Feb. 18)

We can all cite the influential novels — "Ulysses" and "Mrs. Dalloway," spectacularly — that unfold abundantly over the course of a single epic day. In the brutal and tender debut "Real Life," Brandon Taylor graciously grants readers a bit more time with his unforgettable protagonist Wallace, a graduate student who finds his hard-earned defenses and their utility tested over the course of one pivotal weekend.

Wallace, a biochemistry PhD student at a large Midwestern university, is trying to decide if he wants to stay the course or take his chances with real life — as in, what is supposed to be waiting outside of the claustrophobic and artificial limits of graduate school. As a gay black man from a working-class Alabama family he has spent his life "swimming against the gradient" and the labor of that, on top of his grueling academic work, has worn him down. When he tries to talk about it, it doesn't go well; experience has taught Wallace that vulnerability is a trap, and by isolating himself emotionally he has come this far, but at a steep price. The death of his father re-opens old wounds as Wallace navigates a series of fraught encounters with fellow program outsider Miller, whose attentions bear the uncertain possibilities of deep intimacy and trauma.

Life inside the program is a pressure cooker especially for the few students of color, a bond Wallace shares with sunny Brigit, his main support in an otherwise tense lab where he's constantly having to prove himself while white students are given the benefit of the doubt. That makes Wallace's discovery of a ruined experiment, months of his work down the drain and the opprobrium that will follow, particularly devastating, especially when the very good question of whether or not it was sabotage lingers in Wallace's mind.

Hard-science neuroses offer a refreshing change of pace from the usual MFA malaise that fuels so many novels set in academe, though underneath, the same obsessive measuring-up and destructive biases, not to mention the messy social fabric and sex lives, are instantly recognizable. Taylor renders the aggressively Midwestern Nordic cohort into which Wallace has been thrust — a series of race, class, and sexuality danger zones where he's abandoned or betrayed again and again by those who purport to be his friends — with dark wit: he's mentored by the hectoring Henrik, condescended to by a sexually ambiguous Yngve (who claims with zero irony that "Swedes are the blacks of Scandinavia"), menaced by sinister Roman and Klaus, pair-bonded Euro evangelists for open relationships. But Taylor wisely keeps his satirical flourishes in check, never allowing them to downplay or soften the real stakes Wallace faces.

Taylor allows the reader to hear Wallace's pain and yearning so clearly (with the restraint, however, that the close third person provides) that he is bound to leave an indelible mark. And as a stylist Taylor has, sentence by sentence, crafted an experience of bone-deep pleasure for the reader that stands not at odds with the melancholy of the tone of Wallace's story but in loving support of it. The penultimate chapter alone is a knockout, and its end would have been a magnificent closing for the book had the actual final sentence, a few pages later, not surpassed it. — E.K.

* * *

"Apartment," Teddy Wayne (Bloomsbury, Feb 25)

If I were to describe "Apartment" in one word, it would have to be "precise." Wayne's attention to detail and language serves almost as a surgeon's scalpel, gently peeling back layered topics — friendship, class, sexuality — to reveal an engrossing survey of male insecurity and frailty.

This novel is set in 1996 New York, where an unnamed protagonist is embarking on his MFA at Columbia University. He's an aspiring author — mildly self-loathing and lonely when he really thinks about it — who becomes enchanted by fellow student Billy. The two aren't particularly alike. Our narrator graduated from NYU, where his tuition was footed by his father, who is also paying for his graduate studies. He doubts his own abilities to write and to make friends.

Billy is a Midwestern community college graduate who is wickedly talented, and very, very broke.

The narrator invites Billy to move into his apartment — well, technically his aunt's rent-controlled apartment where he is living free of charge. The two initially bond over their shared sense of outsiderdom, while the narrator secretly relishes in the financial power differential.

"He would always have to struggle to stay financially afloat," the narrator says, "and I would always be fine, all because my father was a professional and his was a layabout. I had an abundance of resources; here was a concrete means for me to share it."

But over time, the dynamics of their relationship is subtly upended. It's not one thing that leads to it — there are respective successes, a growing sense of intimacy that is both comforting and uncomfortable — but resentment sets in nonetheless.

There are parts of the book that evoke a certain visceral discomfort, especially in the narrator's more apparently delusional moments, but it carefully written and evocative with an airtight plot. — ADS

Shares