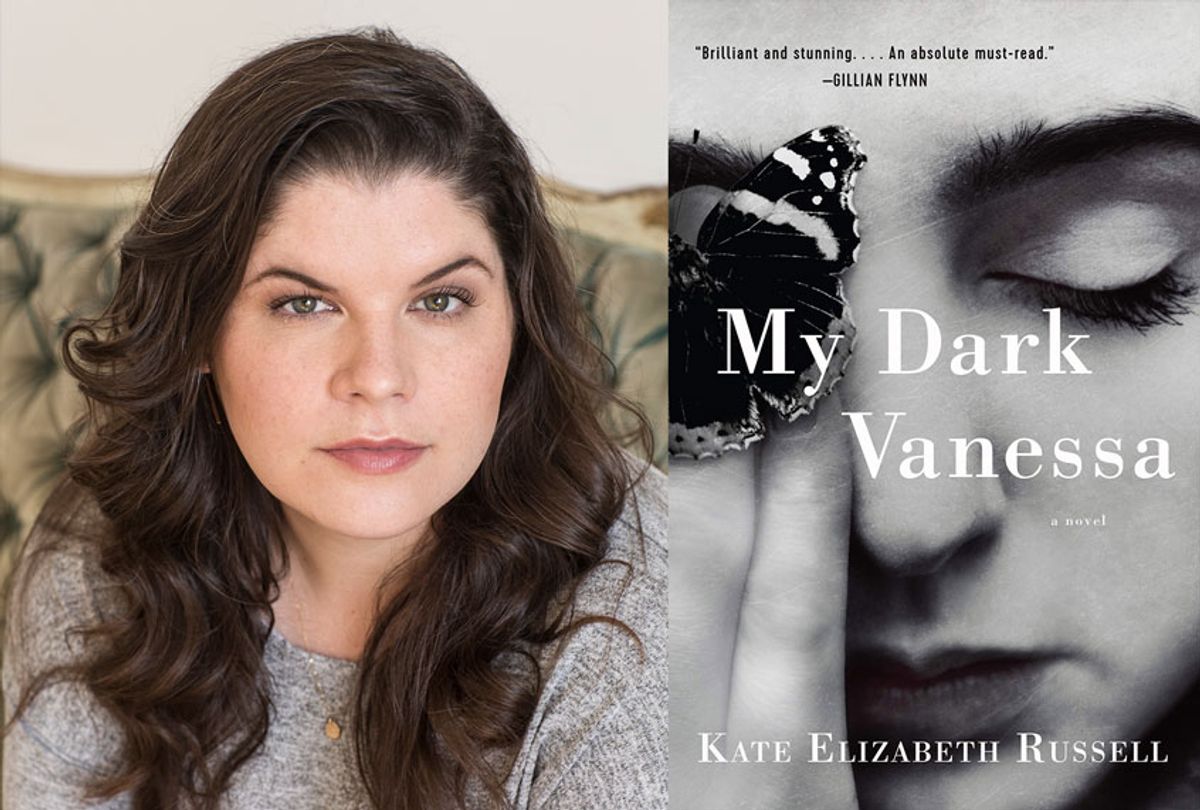

Kate Elizabeth Russell's debut novel "My Dark Vanessa" — already the recipient of blurbs from A-list novelists like Gillian Flynn and Stephen King, sold with a seven-figure advance and all the attendant hype, before it officially landed on shelves this week — did not arrive without some controversy. In the pre-#MeToo era that controversy might have been over the novel's actual storyline, about a precocious boarding school student who believes her teacher's sexual abuse to be a consensual love affair. Instead, the book feels urgently of this moment, mercilessly dismantling the harmful cultural "Lolita" tropes that sexualize teenage girls for the adult gaze and dealing empathetically with the problematic notion of "imperfect victims."

As I wrote earlier in the year in a 2020 books preview for Salon, "My Dark Vanessa" answers Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita" by asking the urgent question of what happens to a Lo who lives, haunted into adulthood by the abuse she suffered as a child and also unable to name it for what it was:

When Taylor, a graduate of a bucolic New England boarding school, announces in the thick of the 2017 reckoning that a longtime English teacher had sexually assaulted her when she was a student, another former student now in her 30s — narrator Vanessa — immediately takes her old teacher's call, reassuring him that she won't allow herself to be "roped into" the narrative too. As Taylor tries to enlist Vanessa as an ally while an enterprising journalist seeks to make her a source for an exposé, Vanessa goes through her own private reckoning with her past. Russell takes us back and forth through Vanessa's point of view, from her sophomore year as a 15-year-old misfit scholarship student groomed for an "affair" by charismatic 42-year-old Jacob Strane that blows her entire world apart and continues to define it up through the unfolding of the #MeToo movement. Vanessa struggles with how to make sense of all that happened to her now that she might finally not be seen, or need to see herself, as culpable — or worse, as the villain of the story.

Russell, now 35, has been working on this book in some form since she was in high school herself. On the eve of becoming the March pick for Oprah's Book Club — a crowning achievement for any author, let alone a debut — news broke via Publisher's Lunch that "My Dark Vanessa" had been dropped from Oprah's high-profile platform. Apparently, the ongoing controversy maelstrom raging around Oprah's January selection, Jeanine Cummins' highly criticized, bestselling novel "American Dirt" (here's an explainer), managed to spill over onto more isolated criticism of the industry's embrace of Russell's novel. As Vulture summarizes:

Meanwhile, My Dark Vanessa, was swept up in a parallel drama. On January 19, a writer named Wendy Ortiz tweeted: "[C]an't wait until February when a white woman's book of fiction that sounds very much like Excavation is lauded." Ortiz, who is Latinx, is the author of a 2014 memoir about a teenage girl's relationship with her English teacher, and her followers were quick to suggest that Russell had co-opted her book, and was yet another example of the publishing industry's long history of valuing white voices and disregarding others. Russell didn't plagiarize Ortiz, and the controversy eventually subsided, even as the anger over American Dirt continued to gather momentum.

The ensuing online discussion — which resulted in Russell issuing a statement clarifying that "My Dark Vanessa" was "inspired by [her] own experiences as a teenager" — apparently set off enough internal risk-averse alarms, and Oprah's Book Club rescinded the invitation.

"We are disappointed by their decision but thrilled to see the incredible response from early readers," a spokesperson from William Morrow said in a statement to Salon, noting that the novel remains a top selection from the LibraryReads and IndieNext lists, as well as Amazon and Apple best of the month selections.

"I'm just excited to publish my first book," Russell said in a statement to Salon through her publicist after the Oprah news broke. "Early responses from people who have read 'My Dark Vanessa' have been so heartening. I'm looking forward to more readers experiencing the novel for themselves, and talking about it — to me, that's what this has always been about."

Before the Oprah news came out, I spoke with Russell by phone on Feb. 24, the day Harvey Weinstein was convicted of sex crimes, including third-degree rape, which gave us a reason to reflect on the last two and a half years of #MeToo. (Weinstein has been sentenced to 23 years in prison.) We also talked about the long path "My Dark Vanessa" took to its final form, the maddening cultural trope of the "Lolita," and more. This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

You worked on this novel for a very, very long time. When did you start, and how long did it take?

I trace the seed of the book back to when I first read "Lolita" at 14. And it broke my mind open, both as an aspiring writer, as this really gorgeous piece of writing that I read and immediately thought, oh, I want to try to emulate this. But it also broke my mind open as a 14-year-old girl reading the story of a 12- to 14-year-old girl being so intensely sexualized, but in a way that felt really romantic and appealing to me at that age.

But I started working on it seriously, I'd say, when I was around 16. And the central relationship in the novel between Vanessa and Strane — though they had different names back in those very early days — that was always there. They were these two characters that I channeled all of my feelings into and all my confusion about trying to navigate this state of being a teenage girl and feeling relentlessly sexualized myself but not knowing how to respond to it, or what was okay and what wasn't okay. Everything I felt I really put into these two characters. And then I studied writing in college, I got a BFA in creative writing, and focused pretty heavily in fiction, and then went straight into an MFA program, also in fiction, in which I was constantly working on this book and turning in pages of it.

And then took a few years off after my MFA when I was working, but still writing and reading a lot, even more than I ever did when I was in school. And it was during those years that I started reading a lot of trauma theory. And it was by discovering that, that I realized, one, that the story that I'd been writing as something like a love story — a dark, complicated love story — was actually something much darker. And that gave me also the theoretical framework that I was able to use to frame my own work in such a way that I felt confident going into a PhD program. Because that was always my hesitation at the thought of getting a doctorate: how to make the argument that [this novel] is academically significant in some way. So trauma theory really gave me that.

And so I entered into my PhD program in Fall 2013. And it was really rare that I was able to have the time and the space and the job security to really devote myself to this book and finally get it written once and for all.

I read in another interview that one of your professors sent it back and said basically, stop turning this in. Given the number of years that this project was incubating inside of you and being worked on in different forms, a lot of writers would have put it aside at some earlier point. What made you keep working on this particular story instead of moving on or thinking, well, this will be my second book, or any of the other things writers in training are told to do by people who are supposed to know better?

I knew that there was this popular idea that all fiction writers come into a creative writing program with a novel, and the point of the creative writing program is to make the writer realize that the novel they came in with is like, s**t, and move on. I was so aware of that. And I feel like that almost made me become even more stubborn, and dig my heels in even more, out of obstinance, you know, from being from Maine and growing up as a southern New Englander. But it did start to feel almost like an albatross that was hanging around my neck, this book that I would never be able to finish. But I just felt so committed, so committed to it. And I would try to write other things. I'd write short stories. Some of which I liked a lot and felt were successful, but nothing else ever gave me the feeling that this book gave me when I was working on it. And so, I think to a certain extent, it just came down to trusting my gut and following what felt right.

And also, I got to the point where I gave up on the idea of it ever having a wide readership or even ever getting published. I certainly still queried agents and I went down that path, but I really didn't expect it to come to much of anything because I think I had just lost all perspective from working on it for 18 years, that by the time I finally finished it, I had no idea what the book actually was. I didn't really know how it would read to someone else. I didn't know if it was quote-unquote "successful" or not. All I knew is that I had finally, finally finished it.

What was that feeling you had when you were writing it?

It's hard to pin down. It's almost this euphoria that I would get when I was working on the book, and this feeling of the characters almost channeled through me. And I also think a lot of it for me — and I'm thinking about this a fair amount now as I'm starting to piece together the ideas for a second book — but with "My Dark Vanessa," I was always so easily able to be in this state of mind where my spare thoughts always went straight to the book. And the characters were always at the forefront of my mind. So everything I read and watched and listened to — everything I experienced — was sort of experienced through the lens of these characters. And that's something you can't really force. And with this book, certainly, it took no effort for me to get to point, and I didn't feel that about anything else I've ever worked on as a writer.

You started writing the earliest versions of the story after reading "Lolita" and trying to untangle what it means, the sexualization of teen girls, and reckon with how our culture depicts them and talks about them. Which is changing, but still. We can remember a time in the recent past when things like an "age of consent watch" were applied publicly to celebrity teens. We were expected to accept that teenage girls were going to be talked about in this way. And what were we supposed to do with that information as we moved through the world every day?

Even at 14, 15, 16, I was so aware of it. I didn't have the vocabulary to express how I felt about it. But the hypocrisy was very clear to me. But I also very much viewed the world in a practical sense, like oh, this is how the world is. This is how men are. This is what heterosexuality is. Which is heartbreaking to look back on. It was really important for me to bring that into the book.

And I tried to bring that feeling into the book through the pop culture references, whether it's Vanessa in the car with her parents paying attention to the lyrics to the song "My Sharona" or her equating herself with Britney Spears in her mind, or certainly the Fiona Apple references. I wanted the reader to come across these references in the text and hopefully pause for a second and make the connection in their own mind of like, oh, are those really the lyrics in that song? I never noticed that before. Oh yeah, that music video, I kind of remember, that let me go look it up and watch it.

As awful as Strane is and how relentless his manipulation is, he isn't working alone. He has this whole culture on his side, normalizing this type of relationship and normalizing it in his own really, really awful behavior. And I wanted to make the reader feel not necessarily complicit in that way, but at least some part of it.

I'm curious about your feelings now about "Lolita" now. It's sort of a maddening book — not because of the book itself but because of the reception of it, how willfully and perhaps even deliberately and enthusiastically it's been misunderstood as the love story it clearly isn't.

It's been turned into such a strange thing over the years since it was published. I love "Lolita." It's still my favorite novel. I've read it I don't know how many times and every time I revisit it, I find something new, or some new layer will reveal itself to me. It's just a remarkable text in that regard. It's so significant to me personally, but at the same time, you can't read it without engaging on some level with what it has been turned into culturally — this archetype of the teenage seductress, you know, what the term Lolita means when it's not used as the book title but as a moniker given to a teenage girl. I know that my book has been referred to at times as "a 21st century 'Lolita'" [and] "a 'Lolita' for the #MeToo era" and I understand that very quick pitch. But my view certainly while working on the book was I wanted to write something that was in response, not just to this text of "Lolita" by Vladimir Nabokov, but a response to Lolita the term, the cultural archetype that we all created, because it still feels so relevant.

And because I think we have gotten a little bit smarter about the ways in which sexualizing girls is wrong and damaging, but at the same time, it's still done. And even the inclination that we have to look back at "Lolita" and [ask] should we cancel the book, should we not read it anymore, is this bad, is it good? That's kind of missing the point. Because it's not the book's responsibility to explain to us why we have turned it into something so far from what I think the the text originally set out to do. That's our problem to figure out ourselves.

I was going to ask you about your feelings about the the term as a trope or as a label. I feel like we're getting smarter about the novel, but if someone says "she's a Lolita" I don't think people necessarily mean "she's being sexually abused by an older man." You know? Are we ever going to have a different concept of what or who a Lolita is?

I feel so cynical when faced with questions like that. But I think the more stories that come out in whatever genre, in whatever medium, that center victimhood in a way that allows it to be really complex, and multi-dimensional, I think there's an enormous amount of work that can be done with that. I think that's really powerful and I am so grateful that my book has been supported in the way that it has already, that it is finding a readership, and hopefully will continue to do. But the more the better. And so that's how I counter my cynicism about the [question] of will we ever reach the point where girls are allowed to just grow up without being sexualized in this way? Maybe not, but I think things do have the power to get better.

Earlier this year, another writer, Wendy Ortiz, compared the reception that your novel received from the publishing industry to the reception that her memoir, which is also a complex story about a girl who was sexually abused by her teacher, received. "My Dark Vanessa" also reminded me of [the Maggie narrative in] Lisa Taddeo's "Three Women" which is reported nonfiction. And you put out a statement saying your novel's narrative was inspired by some of your own experiences with older men when you were a teenage girl. But the author's note on the galley also warns people against trying to figure out the "secret history of the book." So, can you talk a bit about your decision, or your commitment, to writing this as a novel instead of exploring these themes in nonfiction, either memoir or essay form? And throughout the course of working on this book, did you ever get pushback on its genre, or feel any pressure to take a first-person nonfiction approach?

The question of genre, I think, especially when you're writing as a woman and when you're writing in first person, whether it be fiction or nonfiction, and maybe especially when you're writing about sexual abuse — I'm a fiction writer and have always been drawn towards fiction and the spaces to create and invent. I find, personally, a lot of freedom in that ability to invent, and I really don't think I ever would have become a writer if I didn't have that freedom. So it was never really a question of whether or not I wanted to write this as a novel. That was always very clear to me. I loved reading novels when I was younger, I identified as a fiction writer, so it is pretty natural for me to write this as fiction. Even if there were experiences that I'd had that were informing the writing process, everything was always fictionalized and put through this process of becoming fiction.

But certainly, I had times — well, in the writing programs where my work was, I think, viewed as autobiographical, which is, you know, fine, but it would get frustrating sometimes because the responses would feel maybe a little personal in ways that were maybe even a little bit inappropriate. It felt unnecessary to me. And a little frustrating, because I wanted my work to stand on its own. That's all I've ever really wanted.

And going into this publication process, after my book sold and we were figuring out how to bring it into the world as a published book, I wanted to be really upfront with it being a novel, because to portray this book as anything other than fiction, as anything other than a novel, would misrepresent the book and that's not something that I've ever wanted to do. But at the same time there are these obvious parallels between Vanessa and I — even if you just read my very brief author bio on the book it's like, oh, she grew up in eastern Maine, Vanessa grew up in eastern Maine, clearly it's autobiographical — I think that conclusion is jumped to maybe especially often when it's a debut novel written by a woman, especially a woman who's perceived as young, and maybe especially when the novel's written in first person. So I knew that that reading was going to be there. And I just wanted to address it in a way that felt forthright and that drew a boundary between myself and my own experiences, and between Vanessa and this novel that I'd written.

Harvey Weinstein was convicted today. "Convicted rapist Harvey Weinstein" is a thing we can say now instead of "alleged sexual abuser." And I know that his story is different from the story of "My Dark Vanessa" and Strane's crimes in your book, but the reporting on his alleged patterns of sexual abuse of women did blow the doors wide open on a conversation that had been happening, but not quite to the point of where we have ended up, as they say, in the era of the #MeToo reckoning. And the structure of "My Dark Vanessa," with the present-day outing of Strane's crimes by another victim and former student, Taylor, on social media, then going back and forth in time to Vanessa's school days, is similar to the storytelling women have been doing publicly for the last couple of years as well. When you were working on "My Dark Vanessa," did you see that fitting into this larger cultural shift of outing abusers on social media and in the media?

It's still surreal and just baffling to me that the thing that I was working on aligned with real life in such a way. In Fall 2017 I was finishing up the book, because I had to defend it as my dissertation in spring 2018. And so I already had this present-day plotline of another student coming forward and accusing Strane of abuse. Because I'd seen that happening. I'd been paying attention to an increase in stories being reported about sexual abuse at private schools. I know in 2016, the Boston Globe Spotlight Team put out a report about abuse at schools. And I was also really taken by the UVA rape on campus Rolling Stone article and then the audit of it the Columbia School of Journalism did in 2015. And at University of Kansas in 2014, there was a big story, in terms of the campus there, about a mishandling of a sexual assault allegation. And also, I remember the Maryville rape case that happened in Missouri around maybe 2013 and the victim, I think her name was Daisy, wrote an essay on XO Jane [about her] case.

And so all of those things were sort of in my head. And I was really interested in how journalism and standards of veracity and corroboration, how those can cause some friction with stories of sexual abuse in which there are no witnesses or traumatic memory might be slippery or what have you. And then also the use of social media for victims to come forward and say, without having to engage with journalism, or monetization at all, or any kind of corporations, just to make a social media post and say this is what happened to me. I was already working with that. That was a huge thing that I was interested in and wanted to incorporate into this novel.

And then #MeToo started happening. It kind of freaked me out at first because there was such an obvious connection there. And then #MeToo started to get bigger and bigger. I didn't really know what to do. And my first instinct was to just keep my head down and keep writing the book as I had been, but it got to the point where I realized, you know, if my book were to make it out into the world and be published it was going to be read in the context of #MeToo, regardless of how long I had been working on it or what my intentions were.

And so I really had to actively choose to believe in the book that I'd been writing, and believe in myself, even though I was an unknown writer without any major publications and nobody knew who I was, that I had something meaningful to contribute to this conversation because I've been putting in the work for so many years. And I took the plunge and went into the present-day plotline and opened it up so it wasn't just Taylor's one voice speaking out, that she was speaking out in the context of a bigger movement. I made that decision and didn't really look back, and then here we are.

For Taylor, the word about Vanessa has spread around the way that it does around close-knit communities like that there might be a story there to tell. And Vanessa spends a lot of time in the novel grappling with this, and starts off very much not wanting to betray Strane. But Taylor or anyone else inquiring doesn't know Vanessa's motivations or why she's not responding. What do women, or victims, or women who don't see themselves as necessarily as victims, owe the public conversation right now? We went from practically nobody wanting to talk about this to people often asking, essentially, that women open up on demand.

Which is uncomfortable. Or, it feels uncomfortable to me, even if you understand this is coming from good intentions or that it's good to be talking about sexual violence. It's good that it's part of the conversation.

But the way that I approached Taylor's character . . . well, first of all, she emerged more and more as I worked through the draft. She started off as just this little voice on the internet. She and Vanessa weren't living in the same city. They never really interacted one on one. But then in another draft, she sort of emerged more and more and more, to the point where I realized I needed to have them in the same room, at least one time, sitting down and having a conversation face to face. And I tried to write her with as much empathy as I possibly could, because I think she very much believes that she's doing the right thing. And Vanessa thinks that she's doing the right thing. And I think the journalist in in the novel, thinks she's doing the right thing, as well.

And that can be true. I think we often are given narratives in which victimhood is oversimplified. And the thing about the #MeToo movement was that we saw so many stories from women who chose to come forward and chose to share their stories. On a daily basis almost it was like, who's going to speak out today? Or, what abuser is going to be taken down today? And it easily became, it started to feel at times, almost like entertainment, or something that we were consuming on social media. But what we never saw were the stories of people who didn't want to come forward. It's tricky. How do you understand a story like Vanessa's, where she doesn't want to come forward? And she doesn't see what happened to her as fitting into the meta-narrative of the suffering victim who suffers in silence and then comes out with their story and is celebrated and welcomed and feels better, and is subsequently healed. She doesn't see herself fitting into that at all. And so how do we understand her?

I'm a fiction writer; I'm a novelist. I'm inevitably biased, but I think the novel is such a great form for a story like hers, because you get a lot of page space, you get a lot of room to delve deep. And also it's fiction. And so it's not anyone's quote-unquote "truth." It's a story that can belong to whoever reads it. And the reader is free to have whatever response they might have to Vanessa, whether they relate to her or whether they don't, or find her disappointing or frustrating or un-feminist or just completely baffling, all of that's OK. Hopefully what comes out of that is a way to start conversations. And because you're starting from a place of fiction, it's easier. You're not talking about someone's story. You're just talking about Vanessa.

Shares