“Invisibilia” co-creator, “Radiolab” contributor, and NPR reporter Lulu Miller had her first existential crisis at age 7 when she asked her father about the meaning of life. Her world was forever rearranged by his cheery, but to her, bleak response: “Nothing!”

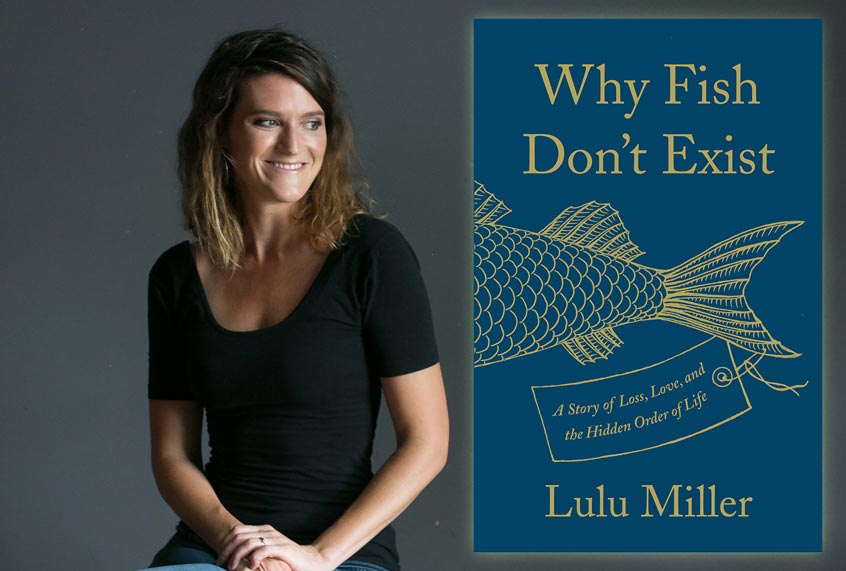

Perhaps armed with this outlook, Miller has continued to seek something that would offer hope or understanding of how others navigate the world. Through her reporting, she’s often delved into science to decode aspects of human nature, but it took an almost unbelievable story to inspire her first non-fiction book, “Why Fish Don’t Exist: A Tale of Loss, Love, and the Hidden Order of Life” (April 14, Simon & Schuster). This is no ordinary fish tale, but instead relates the real-life story of a 19th-century American ichthyologist, a possible murder cover-up, and the horrifying reality of eugenics in America.

David Starr Jordan had spent his life discovering new species of fish, which he then threw in a jar along with a tin tag giving all necessary identifying information. These jars were stacked high at Stanford University when the 1906 earthquake hit, bringing his catch of the decades to a shattering end. Or it would have been for a lesser man. Undaunted, Jordan took needle and thread and began to stitch the tin tags directly onto as many fish as his memory could match.

Was it a Herculean task or a Sisyphean one? Miller found herself intrigued with this fishy folly and began to trace Jordan’s life to see if she could unlock the mysteries of what could make such a man impervious to even the greatest setbacks. Whence came his unshakeable faith that he could succeed in the face of overwhelming disaster? Did this man of science know of a meaning other than “Nothing”?

What she discovered at first was charming – an intellectual obsessed with learning the names of stars, wildflowers, and later as an adult, marine life. Jordan also experienced multiple tragedies of losing family members close to him, but always remained unfazed. He eventually became the first president of Stanford University and a vocal leader of the eugenics movement, even writing publications about genetic cleansing.

It’s a wild ride, with Miller imbuing suspense into this story from a bygone era as each revelation about Jordan becomes more appalling than the last.

Along the way, Miller also shares her own personal journey from attempting suicide, and losing and rediscovering love, to finding some sense in her own life through a surprising fish-inspired philosophy (fish-losophy?) that resulted from her research. How she makes peace with the idea of a man who had done both marvelous and monstrous things involves the book’s coup de grâce that upends our idea of what fish (and we) are in the grand scheme of things.

In a wide-ranging interview with Salon, Miller discussed it all, from the aquatic to the existential. The following has been edited for length and clarity.

I was unfamiliar with David Starr Jordan. When you were looking into him, was it purely because you found this person interesting or did you know all along that there was some sort of story there?

I truly knew nothing. I had heard this little anecdote about the earthquake and how after the earthquake, whoever was in charge of the fish started sewing the label on. So I just knew that someone reacted to destruction in this really confident, almost brazen way. I had no idea who that person was.

And then I literally just wanted to write a pristine little one-page essay of like, man versus chaos, a battle of the little guy against all of chaos. I imagined it would just be a parable like, what was his end? Did he end well? Or did he end poorly? It was an almost foolishly simple question. And then I started to learn about him, and pretty early on just from Google I could see, oh, okay, he became a eugenicist. But I didn’t know the extent. I think there’s kind of this narrative of, “Well many a decent scientist became a eugenicist in that era. It was just an accident of science, you know, like a misstep.” I was like, okay, there’s definitely some darkness and some folly but it didn’t show the hand of how passionately he was a eugenicist and how much he did for the movement. Then I had no clue about the murder involvement whatever, I had no clue about how interpersonally violent he could get, so those were truly surprises that came the more and more I read about him.

Yeah, that’s a lot.

It really spiraled when I saw his fat, giant memoir. Just for me reading it, I started out charmed. I was like, totally he’s a loner, he loves nature, he’s getting taunted … and ugh, I love him. And then it was just, like, ugh just dark. It just got so bad.

Jordan’s instructor Louis Agassiz, the renowned naturalist, as soon as I started reading his ladder hierarchy theory, it started making me cringe – that idea that there’s a moral component, a moral hierarchy to the natural world and even among humans. Of course this leads eventually to various ideas of eugenics that people like Jordan was embracing. Was it obvious, this connection of even how they were talking about the value of marine life that it also relates to the way people are classified and treated today?

Right, I think what happened for me was I realized, “Oh, wow, this guy was involved in eugenics.” I got to learn about the eugenics movement, and how it really got going here. That was the next discovery, of how much a part of American history that was and how popular it was and how the Nazis were putting up posters that said, “We don’t stand alone,” with an American flag on it because we passed the [eugenics] laws first. So then I had my mini like, “Oh my God, we are dirty with this history. Why did I not know that?!”

And then, I still had the sense that this is past, that we’ve moved past those policies. But I was living in Charlottesville for almost 10 years, and and we’re very close to the park where the Unite the Right rally went down. That morning, short buses full of these young – and it wasn’t old people – young men with Nazi flags and the swastikas on shields, were parking in our lawn. Literally they are saying, “It’s just a matter of science that certain races are better.” They’re using the same argument.

To not see that you’d have to be blind, but then just all the insidious ways and even the reporting on the coronavirus when it was just happening in Wuhan. No one cared about the effects of the isolation on the people living there. These aren’t people with the same emotional lives to investigate how they’re impacted. It was seen only as this blight, just this disease that’s being either handled or not. Or today how people who are disabled are in many states . . . they are being just casually, soberly considered to have less valuable lives, that they shouldn’t be the ones getting ventilators.

We think we’re passing in the hierarchy, the moral hierarchy, but we’re not. There are these decisions everywhere, left and right. You hear it in the news, you see it in policy every day where we’re still making this failure of logic, where we still believe there are little moral hierarchies. It’s so alive. And that’s what’s been really astounding to me.

The title of the book, while I know it’s very irritating to people in certain ways – what do you mean, fish don’t exist? – the point is “fish” is symptomatic of a false hierarchy, a lower rung that I’m saying doesn’t exist. And that is the kind of slip of language and slip of logic that we’re making all the time with people. It’s cartoonish and easier to talk about in fish, but . . . we’re not past it and it really could be dangerous.

You explain it fairly simply in the book, but how did you get to the point of revelation that “fish” doesn’t exist as a category of animal, of understanding what the cladists were proposing? It was a radical idea that upset over a century of how we viewed the natural order of the world, and honestly how many people still think. Fish are fish, or so we assume.

Mostly the way in was Carol Yoon’s beautiful book, which is “Naming Nature.” She was the perfect person to explain it because she lived through the revolution in science. She was literally a biology major and then the cladists came into her classroom, pointing out these truths, like the fact that fish don’t exist. And so I just remember reading that book, right as I was learning about David Starr Jordan and kind of seeing his story darken. I thought, “Oh my god, this is such a cool poetic justice for the universe to take away his fish.” I remember having this little part of me that still craves meaning, like the little girl on the deck with my dad, that still wants cosmic justice for a bad guy, to watch science itself do him in. There was something that felt like really thrilling and important to me, in a way that I still have trouble articulating, but it felt like, “Oh my god, every now and then, chaos itself spits out a parable for heathens. Every now and then we actually get moral instruction that’s even about our rules; it’s about chaos. There was something that just felt like, “Oh my god I’ve stumbled onto the coolest, epic parable for heathens.” I felt really thrilled.

But then to truly understand it, took me years, and I had all these, moments of like, “But then what are they?” It took a lot of clumsy conversations with scientists and a lot of doodles on folders of me trying to draw and just make it simpler. It took a lot of slow unscrewing of my own logic, and that was slow. It was slow to get there but but it is cool. I see. Like, do you think do you believe fish as a category doesn’t exist?

Oh, yes I wish there was a way to still say “fish” but acknowledge that is not a category like, “phish,” but unfortunately, there’s already a band named Phish that starts with a “P.” But “phish” would stand for “phony fish.” It would be helpful.

Oh my god I love that. I love that. Maybe we could just call it that. PETA suggested calling them sea kittens. I like “phony fish.” I might borrow that from you and credit you. But it’s like, “Sure, you can still call [fish] that. It’s just not scientifically accurate. But of course, you can call them that.”

You weave in your own personal experiences and trying to find meaning in the book. There’s something that I really identified with, which was having this sort of existential crisis when you’re in childhood. . . . You pinpoint when your father told you that nothing matters in life. It’s all meaningless. It’s the worst epiphany ever. Do you recall what your life was like before that moment? How you viewed life before that conversation?

That felt like a shock to me. I must have just intuitively thought that there was meaning or purpose to life . . . just like I marched off to nursery school each morning; we must be marching into life with a purpose. I do remember the Church of the Latter Day Saints commercials that were big in the ’80s. It was like, cute little mishap and then at the end, some sort of smile and coming together and then it would be like, “Join the church of Latter Day Saints that discovered the purpose of life.” It was like each of them ended with this promise that if you joined, you’d get it.

I think I pictured the meaning or the purpose of life like this little fortune cookie fortune that if you ask the right person or were in the right place, you would learn it and then you’d be okay. You’d be armed with this magical thing to warm all the confusion. I definitely had this sense that there was a meaning that was maybe hard to articulate or hard to find out but that it was there. And so for my dad to just so nakedly and completely saying no, and that everyone else who tells you there is, is lying or trying to comfort themselves. It did feel like a blow. I must have thought that there was some huge universal point to it all.

I could see any other number of children going through this conversation with their father and not taking it in like you did. Their illusions wouldn’t be shattered despite what an authority was telling them. David Starr Jordan, he had this way of viewing life with these illusions that he embraced and allowed him to forge ahead. What is it in people that you think are make them able to embrace illusions versus people who believe otherwise?

I think a lot goes into it. I do believe that most of us do believe that evolution has given all of us that “gift” of some degree of delusion. Because I do think, with consciousness, if we didn’t get a little dash of that with awareness, without some sense of optimism or delusion, we would just be completely paralyzed. So I do think like, we all have that ability just to get through our day, just to even block out the fact that we’re all going to die. Like, how else do put on our pajamas or make the coffee?

I don’t know, but I think that there’s just a scale of how much we let ourselves give in and probably all kinds of things go into how much we let ourselves give in. So probably for me being surrounded by a parent, who is joyfully, devilishly wanting, forcing me to look at the bleakness every morning probably has reared me as someone who’s more looking at a darker, more accurate worldview. Whereas if you’re constantly sunny and things work out for you, and that optimism, that delusion keeps working for you, you’re probably going to keep doing it. Whereas I can imagine if you embrace some form of delusion in yourself or how things work, and then you got humiliated by it, you might be wary of it.

Maybe that’s too wishy-washy, but I do think it’s like we all have a little [delusion]. And then our life determines how much we’re going to hold onto it. And I do think there are some people who are just intuitively more self-deluded. Like David Starr Jordan even talks about how he always had a shield of optimism, and it was so strange and noticeable that people commented on it all throughout his life. So I think maybe he was just spat out that way. Yeah. And being like a white man, relatively well-connected white man, and in the 1800s probably helped reinforce that vision.

Do you think that he might be a sociopath because of that and how easily he lies about everything? There are hints and strong suspicions of murder and there’s the violence Jordan advocates.

I didn’t go that far because the way he behaves I see as far more common. But he did seem to have a shockingly small amount of remorse. Remorse was utterly un-findable in his autobiography. Every hint of self-deprecation is a backdoor brag, like, “I lost the prize because I was I was so ethical,” or because “I was so magnanimous, I wanted a poorer student to win the money.” Maybe that that goes as far as a sociopath but I feel like I’ve encountered people like him who don’t care much about the effect that they may have on other people. Why should they if there’s not cosmic justice? Why not?

You see a lot of people sometimes getting ahead and have never been really punished for their sins because maybe actually karma and cosmic justice don’t really exist, and that unfortunately is the truth of our world. We have all these religions telling us it does exist to spook us into being better. Actually, I think that’s one of the great purposes of religion.

Returning to your part, what were the challenges of doing such a personal story for yourself? You go over experiences and actions that most people keep under wraps, not just in the book, but then you recorded an audiobook. So you had to narrate these secrets in your own life out loud.

There’s two engineers – there’s the producer on the phone and then the sound guy at the studio here in Chicago where I was recording it – and I’m reading the most naked five paragraphs about myself in the third chapter where I’m like, “Ah, yes, here’s my depression, suicide, bullied sister, cheating,” really all in three pages.

And it was like, “Wow, I’m just doing it. I’m putting this out there.” The cheating and also the suicide, those aren’t things I really talk about with that many people. It is a little scary.

In the process of writing and editing, you have to revisit the same ideas over and over and over again to refine them. So in some ways, did that make it more comfortable for you after a while because you’re owning it?

Yeah, actually, I do think time helps. In the original pitch of this book, I had no idea I was going into this stuff . . . but my editor was just like, “This is interesting material but why do you care about this guy?” So I did some real crappy free-writing around it, and then all this stuff came out. It was years of work.

Also, in my work, a lot of the interviews I do is asking people to share huge parts of themselves and I think that I’m healed by that. I know listeners are healed by people being that vulnerable, so maybe it’s time for me to do it too. But it is scary. It’s given me new compassion for people that I just call up and have them feel really dark stuff.

I love Kate Samworth’s scratchboard illustrations that she does with, of all things, a sewing needle. So when did you decide that you wanted this visual component for each chapter? How did that collaboration come about?

From the moment I set out to write what I thought was an essay, in my head I had this picture of man versus chaos – man holding a sewing needle to a tornado of chaos. I wanted readers to see that because I wanted them to understand how I was seeing his story as this almost like Odysseus putting the stakes in the giant, that kind of battle. It just was always in my head that readers might need the visual so they could understand metaphorically what what I was seeing in this otherwise seemingly arcane tale.

When I pitched the book, I wanted her to do it. I’ve known her work for a long time and she works in all forms – these wild oil paints, stop animation, and watercolor. But I’d seen on her Instagram these little scratch drawings and they just reminded me of fairy tale books and where each story gets one drawing. You fall into it as a little kid at the beginning and you don’t know why there’s like a key and a lion, but you want to read it to find out. Then you go back [to look at the picture]. I saw his story as an epic and I wanted to heighten that quality . . . and to play up the parable quality.

You’ve been doing a lot of publicity for this book, but in your regular everyday life, do you think about David Starr Jordan or fish not being fish?

I do think about fish not being fish a lot, a lot with reporting, just in terms of like, “Who am I going to? Who’s my first impulse of who to include in the story? Who am I putting on the hierarchy towards the top as experts? Do I need to immediately rethink that? Do I need to include a different kind of voice? Do I have a bias?” I can’t really see it because that’s the problem with a blind spot or with an assumption; it’s so basic you don’t even think it’s a bias you need to question but I think it’s something that increasingly, my ears are pricked to what categories are people asserting.

This is a small example, but the Lynchburg facility, the colony where Carrie Buck was sterilized was in operation until exactly a week ago. Over 100 years later, the last person finally left because COVID hastened it. At first I was like, “Oh, this is such a happy story. This bad place, finally, no one has to live there, the epicenter of eugenics.” But then I thought, “But where are they going? Is a group home better? What is the freedom?” So just to even think about like the category of freedom or a better place. Is it really? That’s maybe too convoluted, but yeah, I think “Are fish, fish?” is something that has made me hopefully a better reporter, a little more a little more skeptical and just having curiosity about about the truth of categories and about the people who are stuck in them.

As for David Starr Jordan, I think he’s complicated. I think about him in this moment, actually, because he’d be the kind of person who would probably react with creativity. He was good at that, even though he used it for evil. He was really creative in the face of utter destruction. He didn’t spend a lot of time looking back. And so I think like, Are there parts of him that I actually do want to be more like? Are there parts of him to emulate?