The federal government's incoherent response to the pandemic has left public health in the hands of states. Just as the spread of coronavirus varies tremendously among different countries with different politics and policies, so, too, is this observable among U.S. states.

So far more than 124,000 people have died from COVID-19 in our country (more than the Americans who died in combat during World War I), though the numbers aren't distributed proportionally. For instance, as of Friday morning, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts all had the highest per capita death rates while Hawaii, Alaska, Montana and Wyoming had the lowest per capita death rates. Similarly, cases of coronavirus seem to be declining in states like Maryland and rising in states like Arizona, Texas, Oklahoma and Florida. As a precautionary measure, New York, New Jersey and Connecticut are implementing policies requiring 14 days of quarantining for visitors from states whose current infection rates are higher.

Ostensibly, these stark differences should reveal what works and what doesn't from a public health and governance standpoint. And, in some cases, dysfunctional (or functional) state government seems to make all the difference.

Salon reached out to Dr. Ross Baker, a political scientist at Rutgers University, to compare the performances of three neighboring states — Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. As examples of how states overall have responded to the crisis, how do they stack up?

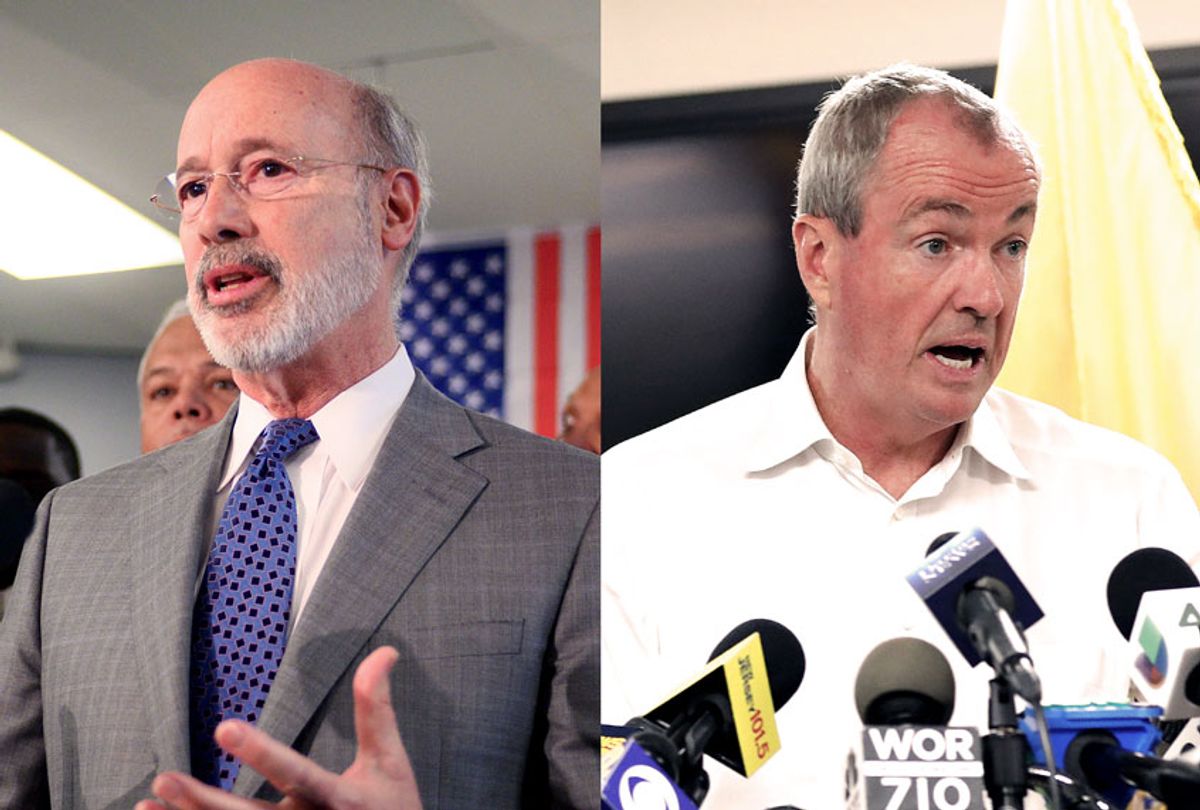

"In the three states you're talking about, I think that there've been a number of similarities," Baker explained. "I think certainly the governor of New Jersey [Phil Murphy] has taken the most aggressive position on things like social distancing, urging testing, and wearing face masks and so on." He argued that New Jersey's situation is unique because of "the severity of the pandemic or the number of victims in New Jersey. New Jersey has had, of the three states, the highest number of deaths and I think the general morbidity rates are much higher as well. So I think that really has to be taken into account."

By contrast, Baker pointed out that Pennsylvania has had a comparatively less serious predicament. "While Philadelphia certainly has had a large number of COVID-19 patient cases, central and western Pennsylvania have had relatively low rates. Governor [Tom] Wolf has been pretty aggressive in terms of social distancing and mask wearing." As for Maryland, Baker observed that Gov. Larry Hogan — who, unlike Murphy and Wolf, is a Republican — "has kind of fallen in line with the Democratic governors in the Northeast in terms of taking a much more proactive position toward protective measures, much more aggressive in trying to get testing done. I think that the commonalities between the three states in terms of the action taken by state government has been very similar. The difference really is the incidents of coronavirus victims in New Jersey and the mortality rate."

Despite Governor Wolf's aggressive public health measures in Pennsylvania, there is discord at the state government level. Recently, state Republican leaders concealed that State Rep. Andrew Lewis, a fellow Republican, had been diagnosed with coronavirus — even though many Democrats had been in contact with him after he was exposed.

"Obviously when the story broke that a colleague had been tested positive for COVID-19, and the Republican leadership did not share that information with the rank and file members... [we thought] it was outrageous," State Rep. Bob Freeman, a Democrat, told Salon. "It really was a irresponsible act on their part. The member in question had attended a number of state government committee meetings, which has been a very active committee as you can imagine during the current pandemic. A lot of legislation has been going through that committee and the committee rooms are not big. It's tough to practice social distancing, that can be very tight."

He added, "He was in close proximity to our Democratic chairman, who has got two small kids. He was in close proximity to two Republican members who quietly self-quarantined after they found out that Rep. Andrew Lewis had tested positive for COVID-19." Pennsylvania Democrats were therefore outraged that "they let this go on for almost two weeks without notifying the rank and file members that one of our colleagues had tested positive and could very well have exposed a lot of members." Yet Freeman added there was a silver lining to this dark cloud: "It finally forced the Republican leadership to come to the table with our Democratic leaders who have been proposing since March the need for certain protocols in terms of how members interact within the chamber."

Dr. Russell Medford, Chairman of the Center for Global Health Innovation and Global Health Crisis Coordination Center, referred Salon to the Kaiser Family Foundation as the basis for his analysis comparing the three states. (His analysis was based on data as it appeared on June 9.)

"if one looks at the different state policies between Maryland, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, there are some differences — although there's a lot more similarities than there are differences, at least in the key areas as far as I can tell," Medford explained.

He said that among the major criteria, "one is a decline in case trends. This is what the daily case counts look like over a seven-day running average. In the case of New Jersey, they've really had maybe a one-day... Everything is less than seven days. We're trying to get more than 14 days as part of the major guidance." After pointing out that Maryland is at "about five days" and Pennsylvania "is two days in terms of consistent days in a row of notable decreases in COVID-19 diagnosis cases," he concluded that "they're very comparable."

Another major factor he identified is the positive testing rate. "As the rate of testing positive rate goes down, it means that you're capturing more and more patients in the population that may not have the disease," Medford explained. "And you're getting to what's called surveilling and our target there is something less than 5% positive rates. So the good news there is that Maryland is at eight percent — which is high, still, but getting better, because the trend is down. New Jersey is already below two percent in terms of positive rates, and that is indicating to me that they are testing a large number of people now and getting a better handle on that surveillance of active disease." Pennsylvania, meanwhile, is at roughly 5.6 percent, "which is getting there to that five percent."

He concluded, "I think all three states are making progress, in terms of the amount of diagnostic testing and the positivity rate, which means you're getting better surveillance and coverage of citizens of your state."

Like Baker, Medford pointed out that New Jersey has had a significantly higher death toll and a higher rate of per capita infections. "There's a complex set of reasons for that, but we anticipate that this disease is behaving in a localized fashion in this country," Medford explained.

In terms of how states should act going forward, former Maryland Gov. Martin O'Malley told Salon that "if we could get this contact tracing stuff down and become a lot faster and more proficient at identifying isolating and containing future outbreaks," residents both of the state he used to lead and the rest of America could rest assured. He emphasized the importance of listening to scientists and basing policy decisions off of their conclusions, although he also said policymakers should sympathize with people who are suffering economically.

"My sense is that the people are ultimately in charge, right?" O'Malley explained. "I'm not sure that there's much repercussions politically, immediately anyway, for governors who are reopening. That's my sense: People are anxious to try to get their life back online and not lose their house and get their businesses going again."

He referred Salon to a recent essay that he wrote, "Contact Tracing: A Race to the Finish," in which he pushes for immediately hiring and training contract tracers, creating a wellness surveillance system, using 911 and 311 systems to survey, communicate and alert on new outbreaks and use cell phone location technology to accelerate contact tracing.

This is imperative, O'Malley argued, because "all the science seems to indicate there will be a future outbreak."

O'Malley is not alone among Democratic state executives who pushes for embracing science in responding to the pandemic. Washington Gov. Jay Inslee — who ran for president in 2020 on a campaign that prioritized addressing global warming, creating a Green New Deal and using science to solve policy problems — harshly criticized Trump for not using science in his policymaking, and argued that Washington's response to the pandemic has focused on doing precisely that.

He also felt there were parallels between how policymakers respond to the problem of climate change and how they are handling the coronavirus pandemic.

"I think there's quite a number of unintentional similarities in these challenges," Inslee told Salon. "And when I say unintentional, they're not ones anybody planned or proposed, but they just are facts. It is true that a failure to follow science and a denial of clear science is very dangerous. It's dangerous in COVID-19. When the president has tried to convince people this was not a problem and we didn't have to do anything about it, that was dangerous. And his efforts to deny the climate crisis, that is also very dangerous. So there's a similarity in that regard."

He added, "There's also a similarity in that science could also be our salvation. We hope that science will be our salvation with an eventual vaccine, and we believe that it can be our salvation in developing a clean energy economy. So there's a cause for optimism in both challenges as well."

In terms of Washington's response to the crisis, Inslee said that "we first tried to mobilize our scientific community to be as scientifically literate as we could very quickly. We declared an emergency. We made decisions about closing schools. We made decisions about banning gatherings. We made decisions about doing the actual stay at home order to close non-essential businesses." He speculated that, by doing those things relatively early on, "we've been relatively successful in bending the curve. But I do want to reiterate that we are so far from being out of the woods right now." Inslee felt that new policies will need to be implemented, including "encouraging people to mask up and to isolate with more success" and focusing on the needs of people in the state's agricultural regions, which have been especially hard hit.

"This is not a moment to declare victory. We're not even half done yet," Inslee said.

When speaking to Salon last week about Trump's performance in his state, Inslee said that the president "has totally failed or largely failed in his obligation to help Washington state through the COVID-19 crisis and the United States." (Salon reached out to the White House for their response, and has not heard back.)

Salon also spoke with former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, who was nearly chosen as Trump's vice president and says he remains in regular contact with the president. (The White House did not respond to a request to confirm this.) Christie also has experience dealing with unexpected crises: When Hurricane Sandy struck his state, Christie's performance caused his approval rating to rise to 74 percent, even as he caught flak from many Republicans for working closely with the Democratic president, Barack Obama. His post-Sandy popularity played a big role in Christie being reelected with more than 60 percent of the popular vote, as well as a majority of the Latinx vote and 21 percent of the African American vote. Christie's Hurricane Sandy response has subsequently faced criticism, but his landslide reelection indicates that Christie knows how to politically succeed during a major crisis... whereas Trump's approval ratings have taken a hit and he finds himself behind former Vice President Joe Biden in the polls.

Christie has his criticisms of Trump, telling Salon that "they were a little bit slow to take the virus as seriously as it should have been taken" and that this hurt Trump politically. Christie added that he felt another reason Trump's approval ratings have never reached Christie's Sandy-era level is "in large measure because of his conflicts with the media, and it's a two-way street." Christie contrasted his observations about Trump and the Democrats with his own productive relationship with Obama, saying that "the difference you saw with Obama and I" was that, even though both men knew the 2012 presidential election was less than two weeks away, they set that aside and worked together.

"I think that states now have to be very aggressive about reopening," Christie explained. "It's time to protect all lives, the lives of the victims of the coronavirus and the lives of the victims of the shutdown." After pointing to statistics about how the shutdown has taken a toll on Americans' mental health, he argued that "the American people never expected to live without risk. They put up with the economic risk at the beginning to flatten the curve, but it was not to keep our shutdown until there was a cure. It was to flatten the curve to make sure that our healthcare system was not overwhelmed. We've done that now." This has become arguable (Salon spoke with Christie on June 5); the curve is no longer flattened, and indeed, cases are rising rapidly in many states now, including California and Texas.

Christie added that it would be "foolhardy" to go back to the way things were before March and insisted that people wear masks, get their temperatures checked before going to office buildings, practice social distancing, frequently wash their hands and regularly clean hard surfaces.

Dr. Joshua Sharfstein, Vice Dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement Professor of the Practice at Johns Hopkins University, made a point not altogether different from Christie's.

"In general, I don't think they're beginning to reopen too quickly," Sharfstein told Salon when asked about states starting to reopen their economies. "Maryland has taken a number of steps that have substantially reduced the spread of coronavirus, and now the state is beginning to open, and we're going to see how effective that strategy is," Sharfstein added.

Sharfstein also argued that the states need "to scale up access to testing as quick as possible" as well as "set up contact tracing effectively, if that is what really slows down the spread of the virus."

Former New Jersey Gov. Christine Todd Whitman, a Republican who served under President George W. Bush as head of the Environmental Protection Agency, echoed O'Malley and Inslee in arguing that we need to focus on science.

"I'm very firmly in the camp of, 'Listen to the scientists, listen to the experts.' That's when we know what we shouldn't be doing, what we should be doing," Whitman explained. She also blasted Trump, telling Salon that "it's been an extraordinarily hard for governors because we didn't have consistent message from the top. We still don't."

She also felt that one of the major challenges to addressing this crisis is that Trump and his fellow Republicans have politicized important public health policies.

"Somehow, and it beats me how, this has become a partisan issue," Whitman said. "Whether or not to wear a mask is somehow a partisan issue. It's beyond my understanding, but it is. And so you have people not taking the kind of precautions that everyone, meaning everyone from the doctors and the people who know, saying, this is the one thing that can really make difference. This is what we need to do, this and social distancing."

She added, "I understand cabin fever, and I understand the jobs that have been lost, and how difficult and terrifying that is for people when they find themselves without being able to earn a living, without being able to support their families. It's terrible. But on the other hand, we're not out of the first trench yet. If we have a second, even bigger resurgence and we have to do something as drastic as close down again, that would really set the economy reeling."

Shares