On Friday, July 3, Fourth of July Eve, President Donald Trump held a stars-and-stripes bonanza in front of Mount Rushmore with all the trimmings for a secular Christmas feast: a military brass band, dazzling fireworks, red, white and blue bunting, and performative patriotism all under the watchful eyes of four of America’s immortalized presidents. In an effort to help his beleaguered re-election campaign, Trump used the occasion to target “angry mobs” of protesters who he claimed were waging a “merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes” and hellbent on “trying to tear down statues of our founders” and “deface our most sacred memorials…”

Though he struggled mightily to pronounce the word on his teleprompter, Trump chalked the pursuit up to a single ideology: “Totalitarianism.”

Of course, the condemnation rang hollow, and not only because of Trump’s struggle to vocalize. If totalitarianism was Trump’s target, it might have helped not to have staged his event in the Black Hills of South Dakota, on the sacred land of the Lakota people in front of a memorial carved by Gutzon Borglum, a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Like the totality of Trump’s presidency, the stunt was a bumbling farce that sought to hide the president’s incompetence and cruelty behind the veneer of faux patriotism and sepia-toned history. This is the language of the Make America Great Again movement that traffics in violently protecting a mythological America that never existed but has held sway and power over the minds of the people for generations.

This gets lost in the discourse. With each newly toppled or endangered statue, public conversation quickly turns to the achievements and follies of the targeted historical figure. They receive a quick once-over on social media and perhaps serve as a blip in the 24-hour news cycle. On a random Tuesday, Andrew Jackson and Robert E. Lee and Christopher Columbus might suddenly be put on trial in the court of public opinion as their bronze likenesses teeter on their pedestals or topple into the pavement.

But the real story has less to do with the public trials than with those defending them. Pulling down old statues put there by previous generations is as old as erecting statues in memoriam. But this moment of outrage by the right in defending bygone institutions, particularly the Confederacy and its cadre of traitors, says more about how power has worked in the United States than it says about history.

Though the standard defense of Confederate iconography has been to lament attacks on “history,” the truth is that these memorials were born of an intentional assault on and weaponized revision of our true national story. Ever since Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House in April of 1865, there has been an aggressive and focused attempt to re-contextualize the Civil War’s causes and aftermath, and that pursuit has been fueled by a desire to scrub America’s story clean of white supremacy.

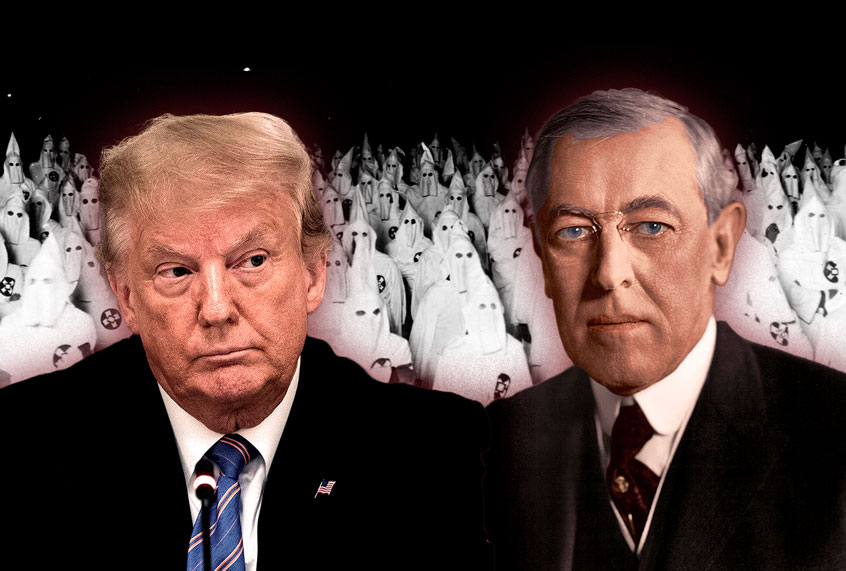

Perhaps no individual played a bigger role in this alteration than President Woodrow Wilson. As a native Southerner, Wilson was a staunch Confederate apologist who spent his academic career rewriting American history as a means of concealing white supremacy and redeeming the Confederacy. In his 10-volume “A History of the American People,” Wilson painted the enslavement of African Americans as a matter of “affection,” describing a necessary, paternalistic order between master and slave. This arrangement, which Wilson described, saw slaves working merrily with “no wrong they fretted under or wished to see righted.” Wilson lamented their freeing, calling them “pitiable because under slavery they had been shielded.”

Wilson’s new history featured the Ku Klux Klan as heroes determined to put the country back to its natural, racist order, and depicted white supremacist lawmakers enacting anti-democratic laws as faithful stewards battling “mischief” by limiting the damage done by “illiterate negroes.” With this post-Confederate America taking shape dependent on white terrorism and prejudiced laws, Wilson saw a country primed for political and economic greatness.

His writings found purchase with an old friend named Thomas Dixon, a southern preacher so offended by a performance of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” that he wrote a series of pro-Confederate novels using Wilson’s histories as guidance. Dixon and Wilson had learned many of the same lessons together as students at Johns Hopkins University and kept in constant correspondence, so when Dixon’s novels were adapted into D.W. Griffith’s movie “Birth of a Nation.” Wilson was thrilled and invited his friend and the cast and crew to the White House for a private screening.

In part because of Wilson’s fake history and the success of the film, Lost Cause mythology took hold in America, leading to reinvigorated Confederate movements and nostalgia. Groups like the Daughters of the Confederacy began erecting monuments. Statues appeared outside courthouses and in public places, reminding African Americans that the Confederacy might have lost the war but still survived in the politics and culture of the United States.

Wilson used this resurgence for his own purposes. Seeing World War I as an opening for America to enter as a world power and broker for peace, he surrounded himself with propagandists he charged with scrubbing America clean of its crime — inequality, and primarily the tarnish of white supremacy — all with the goal of presenting to the rest of the world a nation of perfect equality and liberty. He succeeded in this, rebranding America as a champion of fairness while hiding its toxic racism.

These statues are markers of that revision and serve no purpose beyond reminding Americans that corrosive racist and elitist institutions still control power within the United States. Like the façade offered by Donald Trump, with his predilection for groping flags and spouting meaningless platitudes, they are only symbols obscuring actual reality. While Trump and his supporters protest attacks on “history,” what they actually oppose is the destruction of a weaponized mythology that has served them and their white supremacist pursuits. What they actually fear is a reckoning with a story as hollow as the tarnished statues to which they cling.