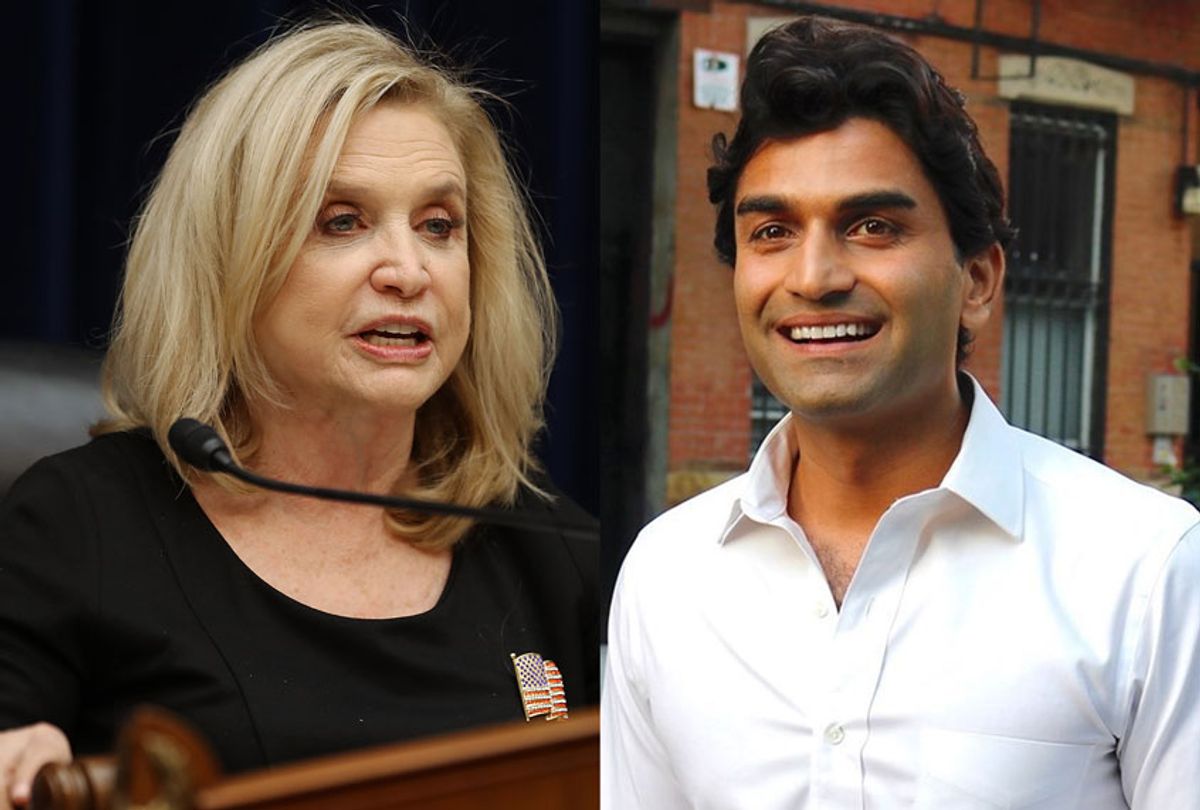

One month after New York's June 23 primary, vote counting in the state's 12th congressional district still isn't complete — and the fate of Rep. Carolyn Maloney, a 14-term incumbent and chair of the House Oversight Committee, is still unclear.

Campaign officials on the ground report that about 12,500 mail-in ballots have already been disqualified in the district, which covers Manhattan's East Side, Greenpoint in Brooklyn, a western chunk of Queens and Roosevelt Island. (In terms of per-capita income, it's the wealthiest congressional district in the nation.)

That's an extraordinarily high percentage — but the problem isn't voting by mail per se, but an unanticipated bureaucratic glitch emerging from a brand new process.

Ahead of the primary, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued an executive order that expanded voting by mail to the entire state, regardless of voter need, to help ensure election continuity amid the coronavirus pandemic.

In prior elections, absentee voters were required to pay for postage, but Cuomo's emergency expansion ordered local boards of elections (BOE) to send voters a postage-paid ballot.

This was a critical difference: postage-paid envelopes aren't typically stamped by the U.S. Postal Service, so a sizable portion of these absentee ballots were returned without a dated postmark — rendering them invalid under the law.

The New York City BOE had instructed USPS offices to postmark all ballots, but it appears that the policy wasn't applied consistently throughout the city, specifically in the 12th District.

Furthermore, the city had never processed mail-in ballots at anywhere near this volume. The BOE says voters returned 408,000 of the approximately 778,000 absentee ballots it sent out this year. For perspective, as the Gothamist pointed out, the total number of New York City absentee ballots cast in all 2016 elections — including all primaries on national, state and local levels as well as the general election — was less than 300,000.

In another wrinkle, for a ballot to be counted, it had to be postmarked by June 23, and the BOE had to receive it by June 30. But without a postmark, it was impossible to tell if a ballot that arrived close to the deadline had in fact been mailed in time, a fact that the Postal Service acknowledged in an email.

"Because of the entry of ballots so close to Election Day there was a high probability that some ballots would not be delivered prior to the election," a spokesperson from the agency's Election Mail department told Salon.

These complications have meant that a final count for the 12th district won't be complete until Aug. 3, a full 40 days after the Democratic primary.

A lawsuit filed July 17 in the Southern District of New York by two candidates and 21 voters estimates that, due to the postmark issue, as many as 16,000 ballots could eventually be disqualified from Brooklyn alone.

The complaint lays the blame in part on the State Board of Elections' reliance on the USPS, alleging that ballots have been accepted and rejected with 'lightning-like randomness.'"

Suraj Patel, a Brooklyn progressive who was Maloney's principal primary challenger, recently signed on to that lawsuit. Maloney led Patel by fewer than 600 votes at the end of machine vote-counting, but the current margin is unknown and the campaigns have offered different accounts.

The 12th District's blank spots are in Brooklyn and Manhattan's East Side. Patel told Salon that the lion's share of ballots without postmarks came from the young and diverse electorate in Brooklyn, where he believes he did well.

"Right now we're down about 1,000 votes in the count," Patel said in an interview, citing internal numbers that campaign staff have collected manually at the ballot counts. "By the time they finish, we think we'll be inside a thousand."

"So think about that," he continued. "A difference of less than a thousand votes, with 12,500 votes that don't count, most of them coming from the most diverse part of the district. It's sad. We'll never know how the people spoke in this primary."

Patel's campaign isn't fully convinced it's a coincidence that the snafu hit his base hardest, and has suggested that these compounded bureaucratic failures amount to "de facto" suppression of minority votes.

A source with the Maloney campaign told Salon a different story. Her campaign's tabulation shows Maloney up by 2,000 votes — double the margin claimed by Patel — and the source said that Patel claims about the disqualified votes are distorted.

"About two-thirds of that 12,500 comes from Manhattan," said the source, who would only discuss internal data on condition of anonymity. "And we beat him about 60-40 in the regular count there. So the numbers don't work: He doesn't have a path."

The larger point here is that it's impossible for anyone could know with certainty how accurate the results are. Furthermore, voters in the district won't know whether their ballot was rejected until the state sends out notices after the general election in November.

"While everyone wants the results to be certified, we can't sacrifice accuracy for speed when it comes to something as critical as peoples' votes," Rep. Maloney told Salon in a statement.

"My team has been at the counting sites every day, and we are thankful for the hard work being done by the Board of Elections workers who are putting everything they have into getting ballots processed as quickly and accurately as possible. Registered voters went to great lengths to participate in this primary, and we owe it to them to ensure that this process is handled with patience and integrity," she said.

The Maloney campaign did not say whether it planned to join the lawsuit. However, Maloney has joined with Patel and two minor candidates in a joint statement, asking Cuomo to order all ballots counted that arrived by the deadline, with or without a postmark.

"Put bluntly: A missing postmark, over which voters had no control, should not disenfranchise those voters," the statement said.

Cuomo has resisted, saying the issue belongs with the courts or state lawmakers. Gubernatorial intervention would literally require Cuomo to retroactively rewrite election law, opening him to accusations that he changed the rules after the game was over.

That could be a risky precedent for a Democratic governor, given the rich Republican history of voter suppression and President Trump's efforts to discredit mail-in voting as prone to fraud. Trump has already hinted that he may reject the election results entirely if he loses.

Patel says that doesn't get Cuomo off the hook. "The voters followed the rules," he said. "They didn't do anything wrong, but they're the ones paying the price. Cuomo wouldn't be suppressing votes — he'd be re-enfranchising voters. It's the right thing to do and it's the thing he has to do."

This thoroughly muddled result in a single congressional district raises serious questions about the strength of vote-by-mail processes in the general election. Combine that with a budget-starved USPS — controlled by Trump political appointees who don't show much urgency to shore up their systems ahead of November — and the outlook grows bleak.

The USPS' Election Mail department emailed a 954-word statement in response to Salon's questions. In the statement, a spokeswoman suggested that despite the black eye from New York, the Postal Service does not intend to make substantive changes ahead of one of the most consequential elections in U.S. history.

USPS "is committed to delivering ballots in a timely manner," the statement says, but "cannot guarantee a specific delivery date or alter standards to comport with individual state election laws."

The agency made clear that it is responsible for educating voters and consulting with election officials, so that they can make informed decisions about how and when they cast their ballots.

USPS places much of the onus directly on voters, who, it says, "must understand their local jurisdiction's requirements for timely submission of absentee ballots, including postmarking requirements."

In response to questions about the funding crisis, the spokeswoman said that "the Postal Service's financial condition is not going to impact our ability to process and deliver election and political mail."

She added that USPS has "ample capacity to adjust our nationwide processing and delivery network to meet projected Election and Political Mail volume, including any additional volume that may result as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic."

However, the Postmaster General secretly issued new guidance suggesting otherwise. The new orders direct major cost-cutting changes that could slow mail delivery.

"If the plants run late, they will keep the mail for the next day," one guideline says.

In an early coronavirus relief bill, lawmakers authorized an additional $10 billion to support the USPS through the pandemic, but the loan stalled amid a dispute with Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin over terms which would allow his department to take over some agency operations.

On July 1, Mnuchin announced a $700 million taxpayer-sponsored bailout of a trucking company and Pentagon contractor worth only $70 million, whose former CEO, Bill Zollars, had been confirmed to the USPS board of governors the month prior. Salon reported that the Department of Justice has accused the company in federal court of crimes committed under Zollars' tenure, including defrauding the Pentagon to the tune of millions of dollars.

Two months ago, the Democratic-controlled House passed another $25 billion emergency aid package to keep the beleaguered agency alive, but the Republican-led Senate has not yet taken up the measure.

Neither the New York State Board of Elections nor Gov. Cuomo's office responded to Salon's request for comment.

Shares