Many aspects about the documentary "Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn" echo strained conversations we're having about race and equality in 2020 – the killing itself, the months of protests that shattered the illusion of comity politicians and popular culture long promoted about New York City, the stubborn refusal of a community to acknowledge its entrenched racism.

But director Muta'Ali opens the film with an especially curious scene fated to strike some in the audience one way and be interpreted another way by others. Gerald Dickens, an emergency medical technician who responded to the call to the scene of the 16-year-old Hawkins' murder in 1989, describes the incident's significance as "one of the bigger ones, besides the World Trade Center."

Then he offers about Hawkins, "He looked like a good kid, you know. He didn't look like a thug or anything."

Unless a person has been keeping up with the more complex conversations on race that have been percolating lately, that quote seems innocuous enough. Those accustomed to reading subtexts others might not understand, including the speaker, may pick up the director's signal in that comment.

Dickens is speaking from a place of empathy. You can see it on his face, hear the heaviness in his voice. There's also racism in that qualifier that Yusuf didn't look a certain way – implying that a few tweaks to his appearance might have made it inexcusable for a white kid to shoot him twice – even though the man probably doesn't mean it or even realize his error.

Surely we know what he means, though. People offered similar thought about Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Ahmaud Arbery, and many young men killed before them and afterward.

In our national trend of people seeking out literature and documentaries in an effort to fill in the many intentional blanks inserted into our educational system's version the Black American experience, "Storm Over Brooklyn" asserts itself as a study in how entrenched denialism is in this country.

We've been watching that play out in recent years as the media industry wrings its hands over whether it's fair or correct to call the President a racist when he makes racist statements or enacts racist policies. People have long gotten used to tasting their own blood after biting their tongues in a commitment to remaining polite in the face of a relative, colleague or friend supporting or committing racist acts, or overlooking coded language.

But it's also in plain sight, in the way we live. With fewer than 100 days before a presidential election that many see as a referendum on the truth in the American promise of liberty and justice for all, "Storm Over Brooklyn" provides a look at a few decades into the past at a reality that very much fuels our present schisms.

The country in 2020 wrestles the tensions over the cultural divides between urban voters and their suburban, exurban and rural counterparts, but those same schisms have been fracturing major cities for generations.

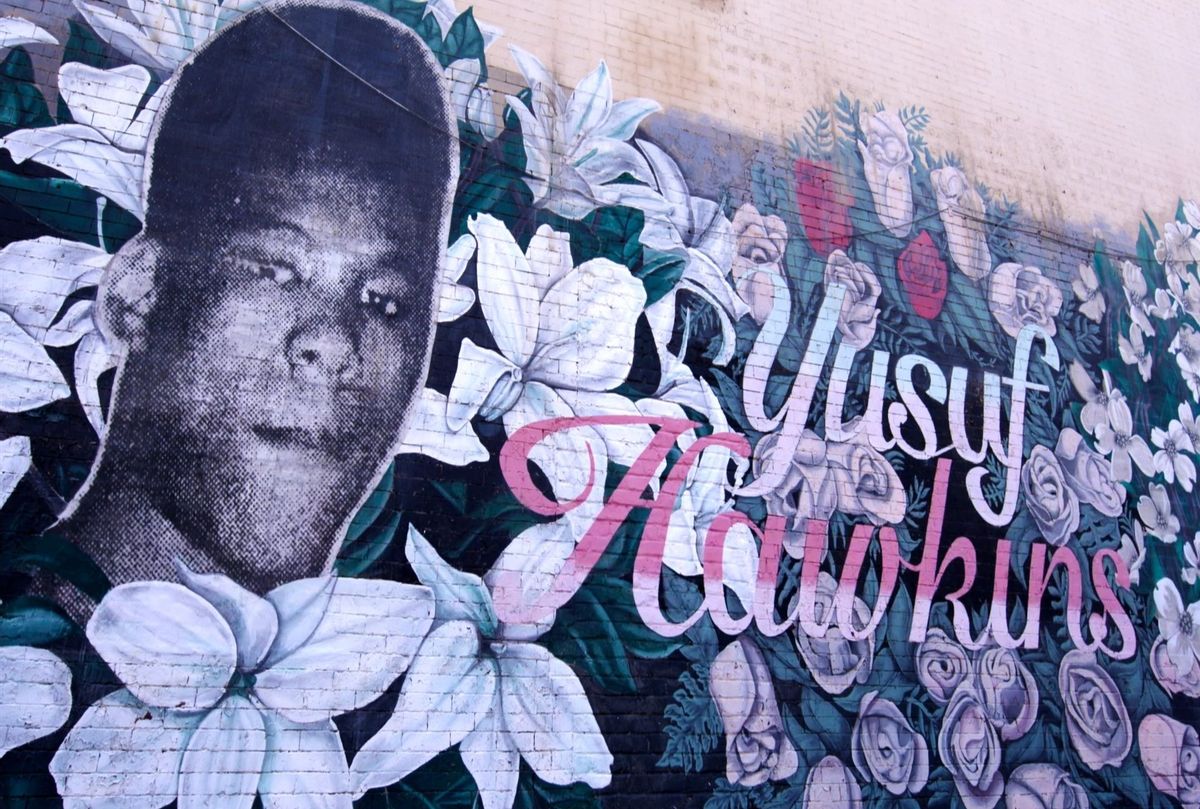

The documentary sets us down in 1989, when Hawkins and a group of friends took a subway train to Bensonhurst, a community dominated by working-class, Italian American families. Hawkins and his friends headed there to look at a car that was for sale; a mob of Bensonhurst men, primed to fight, surrounded and menaced them. One shot a gun into the crowd, striking Hawkins twice and killing him. The city was rocked by months of protests in the aftermath of his killing.

Hawkins' family, particularly his mother Diane, siblings and cousins, steers the narrative by filling in the portrait of a young man whose promising life was cut short, something most of the newspaper and television coverage failed to convey at the time.

Residents of Bensonhurst who remember the night with clarity offer their perspectives, including one of the neighborhood's few Black kids associated with the white mob that attacked Hawkins and his friends, provide their view of what happened. The Rev. Al Sharpton features as prominently here as he did in the many protests demanding justice in the wake of the crime and the court proceedings that followed, as does a representative from the Nation of Islam, who has his own take on how events unfurled.

Voices past and present give "Storm Over Brooklyn" a piercing relevance in the here and now, whether by what they're saying or what they represent. Muta'Ali juxtaposes archival footage from news coverage and police interviews with some of the still-living subjects in the present day, and together it shows a part of America as it is and has been. I'm not referring to the archival footage from the 1989 marches showing white people taunting Black protesters by holding up watermelons; that this no longer qualifies as stunning is telling.

Instead it's the recognition that this tragedy occurred in the same year "Do the Right Thing" became a cinematic phenomenon and in the midst of a new Black conscience movement guided by hip-hop, but also a year after a grand jury discredited Tawana Brawley's claim that she'd been raped by four white men. Hawkins' death and the uprisings that resulted also led to the election of New York City's first and only Black mayor to date, David Dinkins.

But even he campaigned on the selling the illusion of New York City as a beautiful "mosaic," echoing a phrase used by previous New York mayor Mario Cuomo in the late '70s. Do a little research and that viewpoint actually looks more sinister than sanguine. ''I never liked 'melting pot,''' Cuomo is quoted as saying. ''Our strength is not in melting together, but in keeping our cultures.''

That's not in "Storm Over Brooklyn," but interesting to remember when Bensonhurst residents and local law enforcement insist that it's unfair to paint the neighborhood at that time as bigoted. "This is not a racist community," one man says in an interview taking from archival news footage. "We just don't like Black people, that's all."

Looking at New York and America by extension as a mosaic back in 1977, when Cuomo said it, or in 1989, when Dinkins hooked into that dream, is a predecessor to where we are now.

But those moments show the price of maintaining a façade of peace and progress by refusing to admit the existence of bigotry, America's racial denialism has solidified into a massive roadblock slowing our way towards reconciliation and healing, let alone equity.

With even clarity, "Storm Over Brooklyn" shows what that obstacle looks like through the lives of those pressing against it and those who seek to benefit from keeping it in place.

Diane Hawkins' openness in the film also gives her a voice that for the most part went unheard two decades ago; she explains that she was too overwhelmed to express herself in the wake of her son's murder. She says her grief also was swept away in the waves of uprisings that followed, an admission that gives us something to ponder in the present. Her inability to mourn rendered her nearly mute back then; we have an obligation to hear her now and add it to a conversation that might actually move us forward, painful as each step may be.

"Yusuf Hawkins: Storm Over Brooklyn" debuts at 9 p.m. Wednesday, Aug. 12 on HBO.

Shares