Many people first became aware of the Heaven's Gate cult in 1997, when — after an anonymous tip was called into the San Diego Police Department — the bodies of 39 men and women were found in a rented seven bedroom mansion. Each of the bodies were dressed in androgynous outfits with matching haircuts and Nike sneakers. On their arms were "Star Trek"-inspired bands that read "Heaven's Gate Away Team," and in their pockets were $5.75.

The discovery caused an inevitable media frenzy, especially after law enforcement authorities reported it as the largest mass suicide on American soil ( The "Jonestown Massacre," during which more than 900 Americans died, took place in Guyana in 1978). The group believed that once they shedded their physical "vehicles," they would ascend to heaven in a spaceship where they would reach the "Next Level. There, they would be transformed from their human shell into an alien form.

According to group documents, members had taken phenobarbital mixed with applesauce or pudding, followed by vodka, then asphyxiated themselves with plastic bags. The suicides occurred in shifts over three days, with cult founder Marshall Applewhite — known as "Do" — being among the final shift.

The scene was horrifying, but had enough of an aura of oddity to eventually become fodder for late-night television shows and comedy sketches. For example, in its first live show following the discovery of the bodies, "Saturday Night Live" aired a sketch in which the Heaven's Gate members actually make it to space, followed by a fake advertisement for Keds, with the tagline, "Worn by level-headed Christians."

Inherent to all jokes was a question that tends to underlie many mainstream discussions of cults: "How could someone be so easily taken?" The more fringe the group, the more blunt the question — but one that HBO Max's new docuseries "Heaven's Gate: The Cult of Cults," spearheaded by documentarian Clay Tweel, carefully attempts to dismantle and subvert over four hour-long episodes. It's a thoughtfully paced series, rich in original source material and striking watercolor animations in place of reenactments.

The first two episodes aren't the most salacious (if that's what you're looking for, skip ahead to the last two episodes), but they are the most illuminating when it comes to identifying where the tenets of Heaven's Gate fall in the orbit of culturally accepted religious and spiritual teachings.

If — like me — you grew up in or around a Christian church that was heavy on themes of sanctification and purification, some of the cult's ideologies won't sound, well, too alien; just replace the hellfire and brimstone with spacecraft and stargazing.

As this docuseries asserts early in the first episode, a key teaching of both mainstream Christianity and Heaven's Gate was that growing in one's spirituality hinges on shedding one's worldliness. As the Apostle Peter wrote to his followers, "Dear friends, I warn you as 'temporary residents and foreigners' to keep away from worldly desires that wage war against your very souls."

Meanwhile, archived footage of Heaven's Gate members — gleaned by Tweel from early videos of recruiting sessions, public access television appearances, and the now-infamous "farewell messages" from group followers — features them espousing similar sentiments.

"I don't think people know how deep their humanness goes," said Dick Joselyn, a one-time Air Force pilot trainee, who was a member of the Heaven's Gate cult for over a decade, but as another member, Margaret Ella Richter, said, "It's possible to overcome humanness."

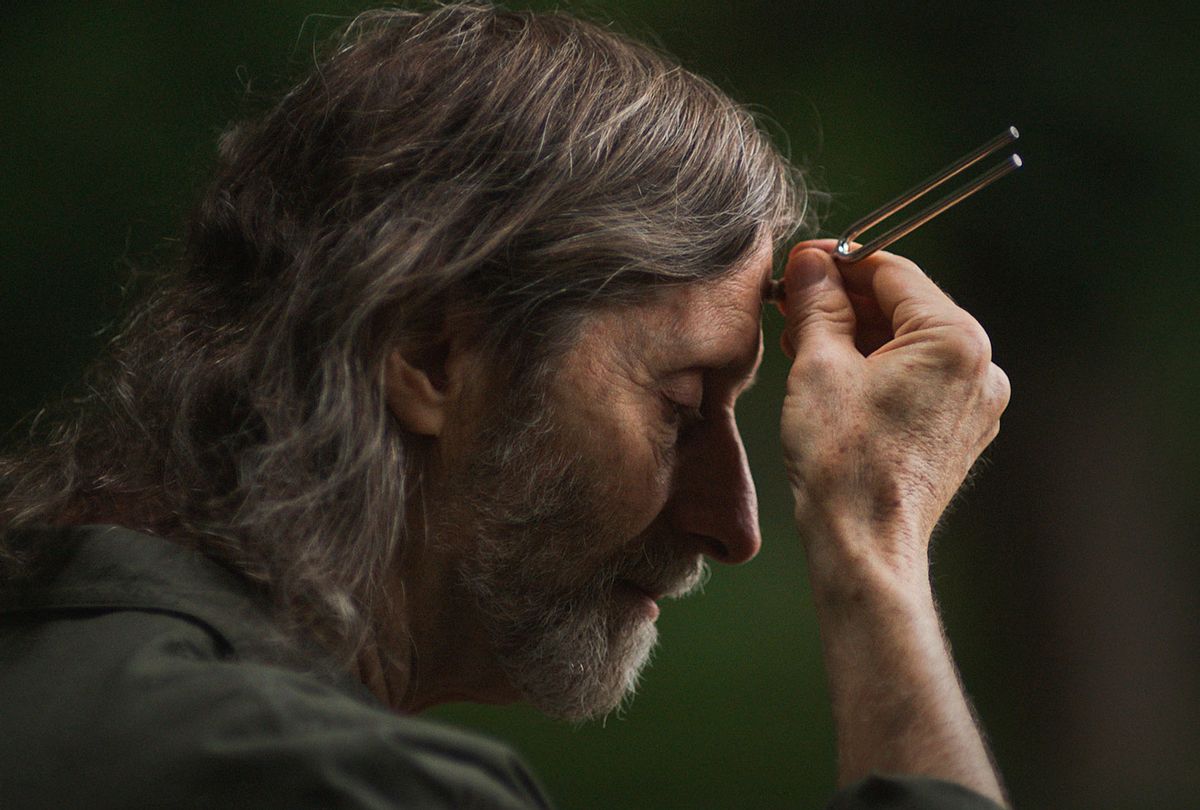

"Heaven's Gate: Cult of Cults" is built on the insight of various sociologists and religious scholars — most notably author and researcher Reza Aslan — who thoughtly weave together this connection, before landing on one of the things that makes a cult a cult. The leaders "break you down and create a new you."

Again, this has a Biblical parallel. Ephesians teaches, "Put off your old self, which belongs to your former manner of life and is corrupt through deceitful desires, and be renewed in the spirit of your minds."

Many of the teachings of Heaven's Gate have a spiritual, though not always Christian, analogue — ideas of ascension (like in the Biblical book of Revelation), a state of enlightenment reminiscent of nirvana, an afterlife. This gospel, if you will, was deeply influenced by New Age concepts, including the idea of "walk-ins," a person whose original soul has departed his or her body and has been replaced with a modified soul. These teachings were also eventually recorded by Applewhite in a series of videos that are deeply evocative of televangelism.

How could people be naive enough to join Heaven's Gate? Well, as one of the featured religious scholars posits, the group was something akin to an errant branch of Christianity (a point that host Glynn Washington made in his popular "Heaven's Gate" podcast, wherein he details his own upbringing in a Doomsday Christian cult.)

It appealed to members for the same reasons churches continue to fill their pews. People want to find connection, they want to feel like they are destined for something greater and that there is evidence of life beyond our immediate and perceptible surroundings. Some former members — who, like the members who eventually died by suicide, were largely educated with strong family ties — still describe their Heaven's Gate years as the best time of their lives. For a brief moment in time, they felt like they belonged.

That said, Heaven's Gates teachings were ultimately dictated by its leaders. Applegate's "spiritual partner," Bonnie Nettles — known as Ti — is presented as the mastermind behind the original recruitment. She was raised Baptist, but her beliefs ultimately became a kind of spiritual grab bag, influenced by New Age teachings, astrology, divination and science fiction.

And once she eventually died, and Applegate was on his own (and absolutely bereft, it should be noted) those teachings became flexible in order to cope with the cognitive dissonance that her "leaving her vehicle early" sparked. That's when, Tweel asserts, Heaven's Gate became more about the messenger than the message, and Applegate transitions from kooky, fringey New Age leader to the leader of the, as he puts it, "cult of cults."

That's when things dip into the salacious — and into more familiar territory for those who already know the story.

Where "Heaven's Gate: Cult of Cults" falls a little short is in its explanation or exploration of Applegate and Nettles' appeal. As leaders, they lack any kind of discernable charisma. While their teachings may have initially been palatable — even appealing — there's a disconnect when it comes to why their followers stayed, especially when they were asked to forsake their families, mainstream society and any source of income.

This wasn't just popping into a church service once a week — it was a full-time commitment, so I was left wondering when things became uncomfortable, what it was about their leadership that compelled their flock to persevere?

That said, "Heaven's Gate: Cult of Cults" is a thoughtful assessment of the mechanisms of how otherwise smart, savvy people are attracted to fringe beliefs.It takes a story that is larger than life and brings it solidly back to earth.

All four episodes of "Heaven's Gate: Cult of Cults" are now available to stream on HBO Max.

Shares