To Ken Burns, boxer Muhammad Ali has always been a hero. “I’d be happy to sit on a barstool and argue with somebody that he’s the greatest athlete of all time,” the filmmaker recently told Salon.

Now that “Muhammad Ali” has debuted, Burns doesn’t need to debate. His four-part, seven-plus hour PBS film makes that case for him.

Burns’ look at the iconic boxer is one of many non-fiction examinations of Ali’s life, but his methodical means of playing the athlete’s career in the context of American history makes his project unique. Burns’ affection, though, is what lends a singular flush of passion and emotionality to this piece.

What moved him, Burns explains, are the way Ali’s life intersects with all the significant themes that defined the second half of the 20th century, from the role of sports in society, the role of athletes speaking out about race, war and politics, about a public figure’s faith and religion and how that forms who they are and how they’re treated.

“All of those things we’re still grappling with now,” Burns explained, “And so he seems to be speaking to us. What seems so interesting in this pass is what an avatar of love he was.”

Even so, the film doesn’t hesitate to depict all the instances where Ali used racist tropes to denigrate and demoralize his opponents in promoting himself.

Salon spoke to the filmmaker about this and other elements that went into making “Muhammad Ali” and how the process forming this biography compares to his previous profiles of other athletes, namely the subject of 2005’s “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson.”

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

I’ve seen most of your filmography, but this one personally compelled me. I think part of the reason is that I actually grew up with Muhammad Ali.

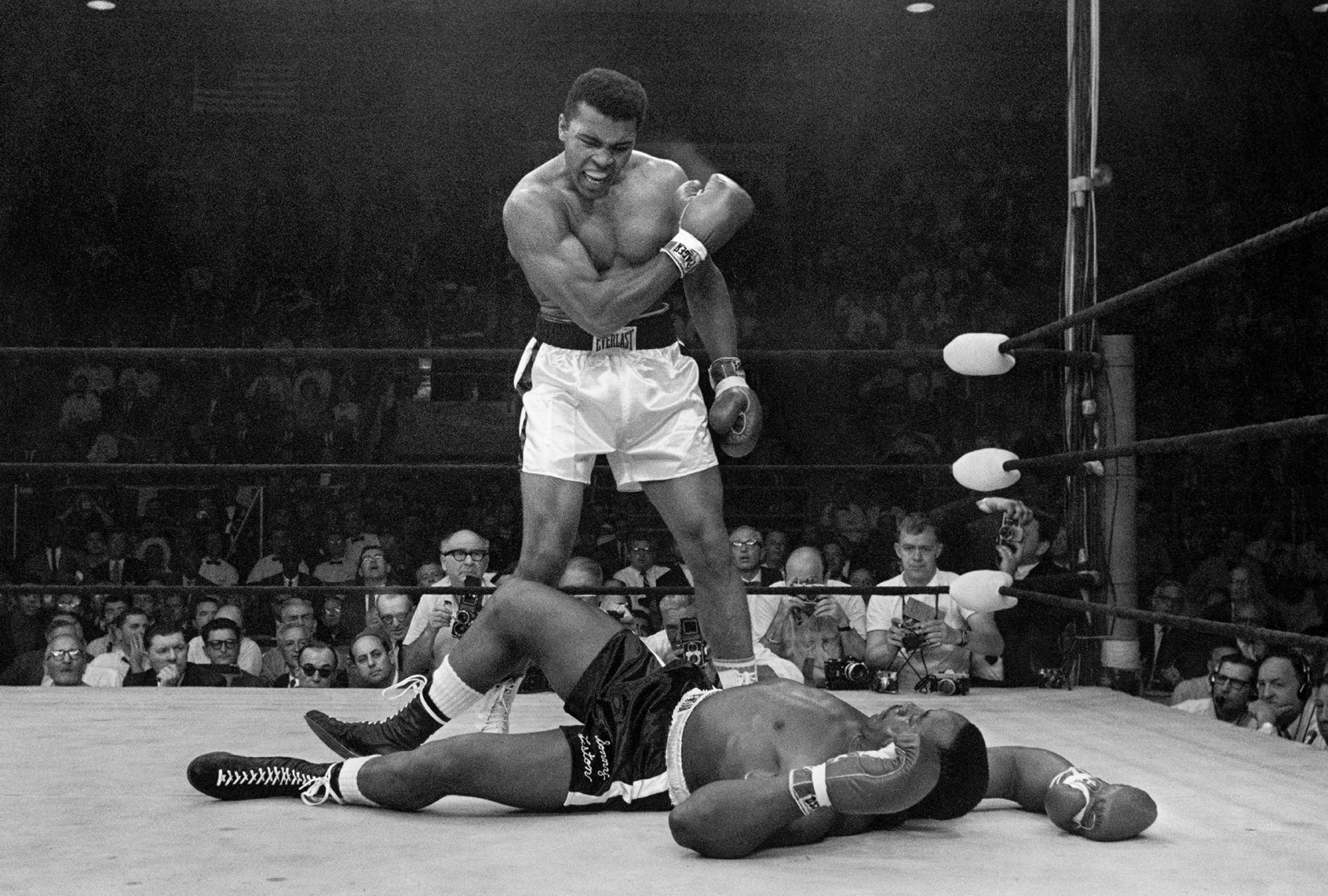

My dad told me about the 1960 Olympics. We watched him sort of rise to the championship fight with [Sonny Liston] and from then on, because we were on a college campus, we loved him. So for all of the divisiveness – which is part of the story, that a lot of people, not just white, but Black people too felt about the way he behaved, his membership with the Nation of Islam, and of course, strike three is his refusal of induction – we loved the poetry, we loved the brashness, the self-confidence, the affirmation. And we loved, of course, his dance. So yeah, I grew up with him too.

I want to go back to what you did with Jack Johnson, which was quite some time ago. You have said that you made the decision to start working on “Ali” in 2013. But I’m wondering if making “Unforgivable Blackness,” planted the seed for this project.

We worked on that for several years. Always the end was pretty well set up about the “Ghost in the House” idea of what was used at the very last moments of our film on Jack Johnson, to inspire “Muhammad Ali.” And I used to say Muhammad Ali fought the government in a decade dedicated to, supposedly, civil rights. Johnson did all his stuff in a decade in which more African Americans were lynched, 1905 to 1915, than any other 10-year period in the history of the United States. So you know, it’s two different things.

And of course, when Muhammad Ali caught up with his story and understood how similar it was, it became inspirational . . . But Jack Johnson was for himself, right? He wanted the same freedom that Muhammad Ali wanted. But Muhammad Ali wanted that freedom for everybody. And that’s the big difference.

One of my favorite moments in the film was us discovering some footage, where after the Supreme Court liberates Ali from his prison sentence on a technicality, some reporter sticks a microphone in his face and says, “What do you think about this system?” Where he could have gone into a dance, a poem, a gloat, whatever it was, he says very reflectively, “Well, I don’t know who’s going to be assassinated tonight. I don’t know who’s going to be denied justice or equality.” It’s just a stunning thing. He’s still in his 20s.

He’s looking at this huge, compelling, unanimous victory that he’s just had, and what a great relief. And he’s responding for all the people in the previous 350 years, Black Americans who had suffered on this continent, including Emmett Till, who was his age and who he saw the pictures of, his tortured and mutilated body . . . And I just am blown away by that kind of sense.

. . . I think that this begins to dissolve over time, as we just begin to appreciate. And then of course, he’s given us so many masterpieces in boxing.

Yeah, let’s talk about that. Something that’s unique with this film is that you let the fight and the footage tell the story. A lot of the music within the film, and I don’t mean the soundtrack, I mean the actual visual melody, is in seeing that footage.

When you first compiled all of your archival material, was there a discussion where you decided, “Let’s just let this play out, so people can actually see these moments that help define who this person is”?

It’s a calibrating process. So a Frazier fight is existing for two years in the editing room – first as a big, large, messy unformed blob, and then gets down and maybe gets too short. Or maybe we learn a new information that in the 14th round, this happened.

And if you could watch the last month of editing, it would be like watching the grass grow. But the pace and rhythm, I think . . . all art forms, my brother said, when it dies, and goes to heaven wants to be music. So all of the analogies of the editing room are all musical ones, like “Could you hold that another beat? Another two beats?” . . . Just so that the reception of that information for someone who’s given us their valuable attention, we do not in any way dishonor or spoil, or allow them to fall out of the narrative.

A lot of people in their own way, as much as they feel about somebody that they don’t know personally, have very strong feelings about Muhammad Ali that the film addresses, and you speak a lot about the love that comes through for him.

There’s also a lot of evidence in the film of him using racist tropes to promote himself and disparage other Black athletes. How do you approach that as a filmmaker, and did that aspect of Ali impact your personal feelings, the more you dug into that aspect of his personality?

You know what? Regardless of how much love I have for him, or how much disdain I have for him, that’s immaterial. As I’ve I said before, it’s important for us to lift up the rug and sweep out the dirt. Our last film was on this toxic masculine macho guy called Ernest Hemingway, who you then learn in the course of our work is very gender fluid, and experimenting in ways that are not so crazy today, but certainly were 100 years ago.

Same with Muhammad Ali. What makes a good story is knowing that Achilles had his heel and his hubris, along with his great strength.

[USC professor] Todd Boyd says it best, with regard to Joe Frazier, when Ali’s using language that a white racist would use against a Black man. This is the ultimate, hip conscious Black man doing this, right? And [Boyd] just shakes his head and says, “I think in this case, he used his powers for evil rather than good.”

And then you say, oh right: Muhammad Ali is like a superhero in the way these nauseating Marvel characters are not. This is a real guy in front of us whose life is like a Greek mythological story, like Achilles is playing out strength and weakness right before our eyes. Our own lives are his life, but written much, much smaller, which is why, I think, everyone is drawn to him, even if you come out hating him for that.

Nobody is ever one thing. And this is the great mistake we make, particularly in a binary computer world and kind of superficial media culture, where it’s just on or off, black or white, gay or straight, rich or poor, male or female, red state or blue state. It’s a dialectic that does not exist in real life.

Because he was living history for a lot of people, Muhammad Ali carries great symbolism with it. That’s true of a lot of sports icons, as you know, having produced films about Jack Johnson, Jackie Robinson and, of course, your series on baseball. But I wanted to ask if you think there’s a difference in the weight of what Ali symbolizes, based on the fact that he was a boxer?

Yeah, I’m not a boxing fan. But I think the best description is in Episode 3 at the end of the third Frazier fight, when Jerry Izenberg, obviously recalling what he wrote in his column at the time, talks about this: They’re not fighting for the WBA championship, they’re not doing the championship of the World Championship. It’s the championship of each other, and they’re two men on an ice floe, and to each the other is Ahab’s white whale.

That tells you all you need to know about what boxing is.

“Muhammad Ali” is currently streaming at PBS.org.