It's never an issue for this U.S. Supreme Court to move the goalposts, change the rules or simply make up them as it goes along. No knowledge of constitutional precedent, American history or even textualist theory is necessary to understand this radicalized court. An entrenched conservative supermajority has the power to bulldoze it all. And so they have.

This disciplined approach and fanatical agenda has had deep consequences. It has unleashed billions of dollars in dark money into our politics, eviscerated much of the Voting Rights Act, green-lit partisan gerrymanders that entrench one-party conservative rule, dismantled giant pieces of the regulatory state and demolished reproductive rights in much of the nation.

Now this grim band of robed ideologues appears ready to march us deeper into minority rule.

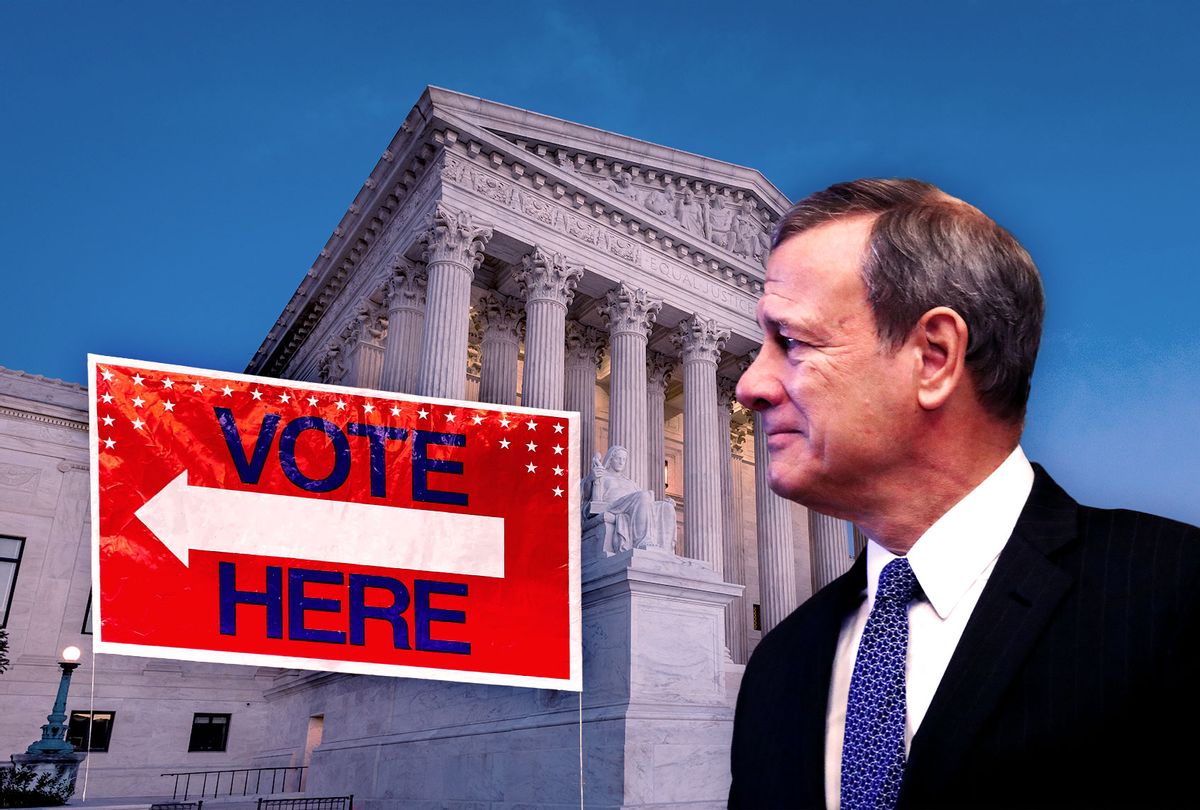

Last week, the court heard oral arguments in Moore v. Harper, a case from North Carolina brought by determined Republican lawmakers and funded by right-wing dark money. Those legislators in the Tar Heel Statehave spent the last dozen years drawing gerrymandered maps that guarantee their party more than 70 percent of the congressional delegation in what might be the America's most closely divided state.

North Carolina's state supreme court, equally determined, struck that rigged map down this year as a violation of the state constitution's guarantee that all elections must be free and fair. The court ruled that maps surgically drawn to ensure Republicans would win at least 10 of the state's 14 seats in the U.S. House, regardless of how citizens voted, fell far short of that standard.

Republicans bristled when the state court disallowed their tilted maps, and responded with a federal lawsuit asserting that the U.S. Constitution provides the state legislature with the sole power to manage the time, place and manner of federal elections. This notion has become known as the Independent State Legislature doctrine (or ISL), and it claims, wildly, that state constitutions and state supreme courts cannot constrain state legislatures at all when it comes to how elections for federal office — the House, Senate and, yes, the president — are administered.

This insane and dangerous theory is not grounded in American history, basic checks and balances, constitutional theory, or the last 233 years of our politics. It was the underpinning for Donald Trump's "Big Lie."

It's an insane and dangerous theory, not grounded in American history, basic checks and balances, constitutional theory, longstanding practices of judicial review, or even the reality of the last 233 years of our politics. This discredited and anti-democratic notion provided the underpinning for the "Big Lie" that sought to keep Donald Trump in power on Jan. 6, 2021, with phony slates of presidential electors from states Trump did not actually carry.

What's more insane is that the Roberts court seems ready to embrace it, at least in some reading.

Most legal analysis of last Wednesday's oral arguments has concluded that the court does not seem likely to endorse the most maximal reading of the ISL theory. While it's never safe to predict outcomes based on oral arguments, it seemed apparent that three Republican justices (Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch) were ready to embrace ISL, three liberal justices (Elena Kagan, Ketanji Brown Jackson and Sonia Sotomayor) stood opposed and the three other conservatives (John Roberts, Amy Coney Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh) appeared open to a more limited version of ISL.

But a compromise between reality and crazyville that stops just short of bonkers doesn't provide any comfort. And any half-loaf ISL that emerges from Wednesday's arguments is an egregious and intentional misreading of the actual threat to American democracy — and one that will make it even more difficult to address the real dangers. If you listen to the three hours of oral arguments in this case, you might come away thinking that the problem we face is a rash of runaway state supreme courts asserting extra-constitutional powers to thwart state legislatures from fairly drawing maps and administering elections.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

But absolutely the contrary is true: State legislatures, after gerrymandering themselves into permanent power and insulating themselves from the traditional controls of the ballot box, then gerrymander congressional maps for their side, lawlessly brush aside citizen-driven ballot initiatives and constitutional amendments meant to rein in their powers, and embrace nonsensical conspiracy theories about voter fraud when there is no voter fraud. The ISL theory would worsen all of this dramatically, potentially freeing state legislatures from almost any constitutional checks and virtually guaranteeing that the nightmare scenario barely averted in January of 2021 has a better chance of succeeding next time.

This theory could also put an end to independent redistricting commissions and many other voter-driven electoral reforms won via statewide ballot initiative. Perhaps most importantly, in some states, supreme courts have been the last remaining avenues for citizens to reclaim their democracy from legislatures so gerrymandered that lawmakers need not listen to anyone. The ISL — in most any version, "compromise" or otherwise — could shut down the best path voters in North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and elsewhere still possess to restore representative democracy in states that have been tilted into minority rule by extreme gerrymanders. This is the very reason why this theory has surfaced now: State courts, state constitutions and citizen-driven initiatives have proven the only way around GOP gerrymanders that have blocked the will of the people in some states for more than a decade. This can be understood as the latest ploy in a relentless, systematic effort to shut down every avenue of reform that threatens GOP control.

Chief Justice Roberts is no institutionalist and incrementalist, trying to fend off the arsonists to his right. He's trying to achieve the same destruction more slowly, pulling out the support beams one at a time.

It is sadly unsurprising that the Roberts court, once again, appears to be siding with forces that would worsen our crisis of democracy. After all, this court has repeatedly struck the match and acted as an accelerant to constitutional crisis again and again, whether setting billions of dark money loose in the Citizens United decision, gutting crucial provisions of the Voting Rights Act or enabling this gerrymandering free-for-all.

But it's both surprising and depressing that court watchers and the news media continue to portray Roberts as an institutionalist and incrementalist beset by conservative revolutionaries. In fact, the chief justice is not trying to stop the arsonists to his right, but only seeking to reach the same extreme destination more slowly, pulling out the foundational support beams one at a time rather than setting everything ablaze.

Thomas, Alito, Kavanaugh and Gorsuch have all previously intimated that they might be on board with some version of ISL, or were at least ISL-curious. Roberts has been more difficult to read. In his stinging dissent in a 2015 case that narrowly upheld the constitutionality of Arizona's independent redistricting commission, the chief justice embraced an early version of ISL, insisting that the word "legislature" in the Constitution's elections clause meant exactly and only that. But then in another redistricting case, 2019's Rucho v Common Cause, Roberts wrote the 5-4 decision that closed the federal courts to partisan gerrymandering claims. He insisted, however, that he was not leaving complaints about unfair redistricting to howl into the void. State courts and state constitutions, he insisted, could tackle those by themselves..

That now looks to have been bait-and-switch. Last Wednesday, Roberts walked this tiny bit of hope from a brutal and poisonous decision all the way back — and media court-watchers who still portray him as a humble caller of balls-and-strikes rather than a savvy right-wing tactician missed it. Roberts insisted that those who took him at his word about state courts had misread his opinion in Rucho; he said the real point of his decision in that case was to highlight that there are no manageable standards to determine when a gerrymander has gone too far. He suggested that state constitutions are just as vague on that topic — musing, for example, that the clause holding that "elections must be free and fair" was itself profoundly unclear. For a so-called textualist and originalist, Roberts often seems not to say what he means, or to mean what he says.

Alito appeared just as disingenuous, asking at one point whether it would actually further democracy "to transfer the political controversy about districting from the legislature to elected supreme courts where the candidates are permitted by state law to campaign on the issue of districting."

This is a question worth breaking down. In states like Wisconsin, Republican lawmakers have embedded themselves into permanent near-super-majorities, guaranteeing themselves almost two-thirds of state legislative seats even when Democrats win hundreds of thousands more votes. That gerrymander is now well into its second decade. Transferring the political controversy to an elected supreme court and justices who are willing to act on behalf of voters, not politicians, would, in fact, be just about the only path to restore any hope of majority rule.

All of this sets Roberts up to propose what too many Supreme Court reporters will call a compromise, but is actually just a slower walk off the cliff. Perhaps it will involve some new multi-part standard that makes it more difficult for state courts to interpret state constitutions on election issues. Perhaps it will make it easier for federal courts, now stocked with junior Federalist Society acolytes, to police state supreme courts that dare interfere with GOP gerrymanders. Then, the next time the issue appears before the Supreme Court, Roberts will push things just a little further, just as this court did with voting rights and redistricting. When the court dismantled the Voting Rights Act's pre-clearance protections in 2013, the conservative majority insisted that Section Two of the act remained in effect and would prove sufficient. Then it turned its attention to eviscerating that in a series of new cases.

The ISL would empower legislatures that have already proven, time and again, that they cannot be trusted to draw representative maps. It could be enacted by a Supreme Court that continues to show it is unwilling to ensure free and fair elections.

Read more

about the independent state legislature doctrin

Shares