We're on year three of the pandemic when I receive my first high-five through a laptop screen.

It's from Amanda Shires, who's just learned we both have MFA degrees in poetry. Shires earned hers from the University of the South, School of Letters in 2017, which the singer, songwriter and fiddle player says she pursued "to get more tools in the toolbox. For so long, I felt like to have credibility as anything, I had to have some kind of documentation to prove that it was OK to do what I was doing, and that just comes from — You know what it comes from."

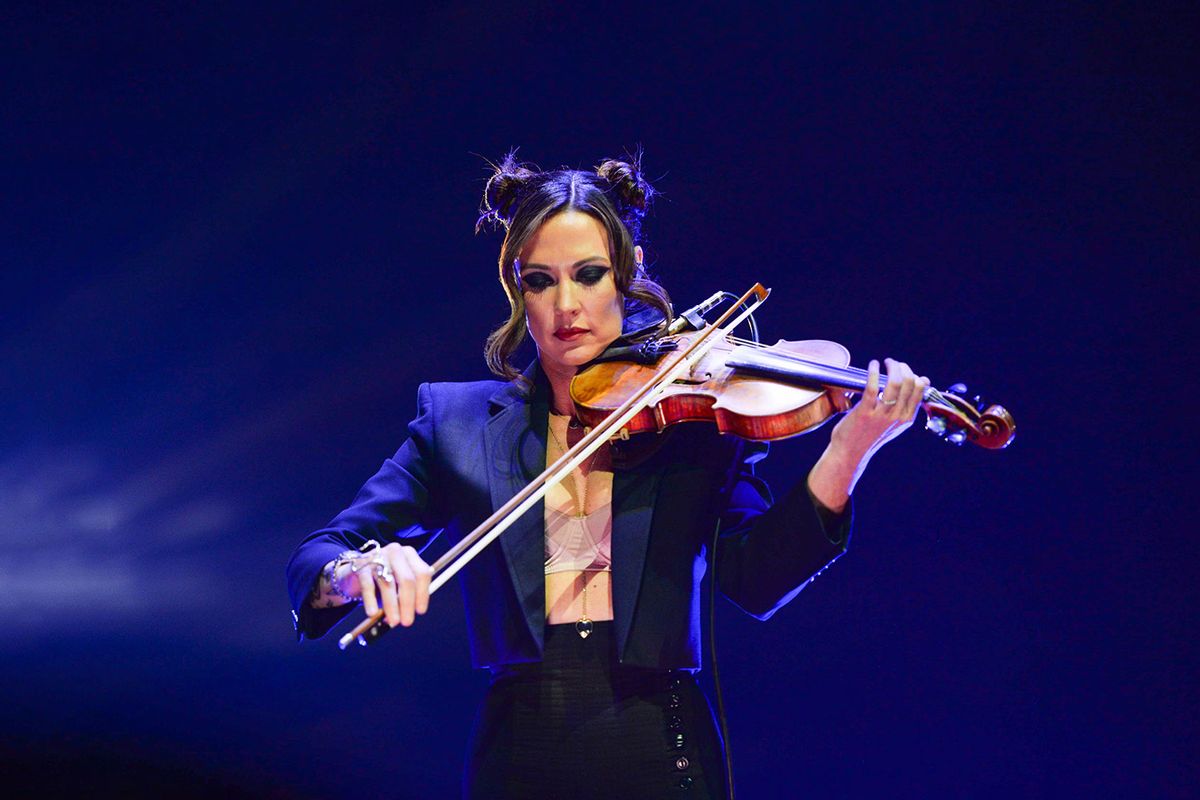

I do know, and we talk about the sexism, double standards and toxicity of the music industry, which almost caused Shires to quit the business for good. But she emerged stronger than ever. Her 2022 album "Take It Like a Man" has been called her "finest release" by NPR while Variety said the album "prov[es] what a tough character she really is, exploring territory that singer-songwriters a little less sure of themselves would fear to tread." You become stronger through fire, and hers includes a very public marriage with musician Jason Isbell, whom she performs with in his band the 400 Unit.

Along with performing dates with Isbell, she's also on the road touring in support of "Take It Like a Man," her seventh solo album. And less than a year after its release, she has a new album out on June 23: "Loving You" with Bobbie Nelson, the late musician and elder sister of Willie Nelson. "Loving You" highlights some of Nelson's favorite songs, including a version of "Summertime" featuring Willie Nelson.

A pianist and composer, Bobbie Nelson died last year at the age of 91. Shires and Nelson first met in 2013, but decades before, Shires as a teenager had witnessed her playing: the first woman Shires had ever seen who was a professional sideperson for bands. That was what Shires wanted to be more than anything.

And she was — and is. But Shires has also stepped firmly into center stage, where she belongs, even though her voice may sometimes shake with the emotion of standing up and saying what she means. That quiet strength is a lot like that of one of her favorite poets, Ada Limón, whom Shires credits with getting her through COVID. We talk about exposing our vulnerability in writing and, like Limón's poems, not being tough all the time. "There we are," Shires says. "We need to just accept our warbly voices."

Salon talked with Shires about "Loving You," Isbell, birds and crying.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and condensed.

How did you first find music?

Accidentally. Pre-mental health, I think, as a kid experiencing my parents' divorce and all kinds of tumultuous family life, I didn't really have any means to express that. I happened to walk into a pawn shop with my dad. He was getting – not a new knife, but it was a pawn shop; he was getting a replacement knife. I saw a fiddle on the wall, and I convinced him that I needed it.

"I would try to book myself gigs, and people would say 'But you play the fiddle.' I was like, 'That's not all I do.'"

I didn't know why. We weren't a family of any kind of money . . . But he eventually spent the $60 for the fiddle. We took it home under the condition that I learned to play it because it was serious. It was money. I broke all the strings, and after summer was over, my mom started enrolling me into music classes at school . . . A few years later, I started getting bored, and my teacher noticed. He said, "I've been working with the Texas Playboys," and I was like, "What's that?" He said, "It's Western swing music," and I said, "That's interesting." He showed me my first fiddle song, "Spanish Two Step." I came out of the lesson, and I said, "Mom, I want to be a fiddle player."

You joined the Texas Playboys at 15?

Yeah. I was playing with them some before that, but I didn't start getting paid with them until I was about 15.

That's a big deal for a 15-year-old to earn some money.

I didn't realize that it was such a big deal. The money was cool, but I didn't really see it. My mom just held on to it for me and kept me in lessons and continuing to have gas to drive to those types of things. It was a beautiful experience, and looking back, I see how important it was. But to me, it was just, the music just spoke to me.

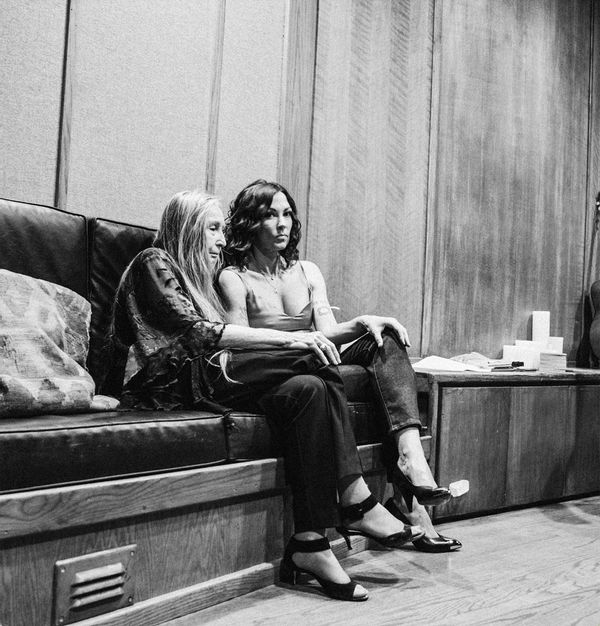

Amanda Shires and Bobbie Nelson (Photo courtesy of Joshua Black Wilkins)

Amanda Shires and Bobbie Nelson (Photo courtesy of Joshua Black Wilkins)

"So much of our identities are wrapped up in what we're supposed to be."

When did you start writing your own songs?

I started writing my own songs kind of late. Probably it started about when I was 20 or 21, but I don't guess that's too late. I was a sideperson still. I started writing some songs, and this man named Billy Joe Shaver, who I was working for at the time, told me that they were good. I believed him because he was not known for saying nice things. I eventually moved to Nashville and pursued my dreams of becoming a waitress after having had a stable and great life as a sideperson.

It was different to move into the front person role, right?

Oh, completely. First, I had to shed the side role skin, and I could only really do that by getting out of Texas because I would try to book myself gigs, and people would say "But you play the fiddle." I was like, "That's not all I do." They said, "Yeah, but . . ." It was kind of different then too. Not a lot of women booking.

I was going to say, it's hard as a woman to get people to see you as anything, let alone to see you as more than one thing or as moving into a different thing.

That is the truth. So much of our identities are wrapped up in what we're supposed to be, our perceived identities . . . But lately I've been seeing hints toward sea changes, good and bad. I mean, even journalists talking to women has been such an amazing thing. I feel as if I sound like one of those people that's like, "I remember when we didn't have cars." But this is still a huge deal, and we're not done.

How did you start singing? How did you develop your voice as a singer? Did you always know you wanted to sing too?

Hell no. I still don't think I can sing.

Oh, no. You can.

It was at first out of necessity. I wanted to work in music, and when I was young, I thought, "I want to be a sideperson. I guess I love whatever that is," and they needed harmonies, so I started singing harmonies some with the Playboys and other folks. At first, I would stand 10 feet from the microphone, scared of the sound of my own voice because in your head, it sounds different than it does when it comes out.

"She was the only proof for a long time that I saw that you could be a sideperson and be a woman."

Luckily, I was in a place that fostered that. Then I sang my first solo song with the Texas Playboys, and that was a complete disaster. But it was handled with such elegance and kindness. Everything I do in music now, I compare it to that experience. When I started to sing that song, we'd practiced it, but I got up to the microphone, and nothing came out, and they all turned around and laughed. And it was awesome. Leon Rausch and Tommy laughed some more, and then Leon held my hand, and we started singing. Then, the rest was there.

And you start to get used to it. It's a weird thing for everybody to be looking at you while you're singing. A lot of people have interesting music listening faces . . . I don't think people know that, but you're just like, "Wow, that's not encouraging."

They have resting mean face when they're listening.

Exactly. Resting chill, I've been at work all day, face.

I know that you have written a song for Leonard Cohen, and you've also covered songs by him.

And I'm covered in Leonard Cohen on my right arm. [shows tattoos.]

I was going to ask if he was an influence, but obviously he was.

We were supposed to probably have a life together. I'm just such a huge fan of his work, and I identify with the process. He wrote songs very slowly – and I do that too, and he had problems with stage fright at first too. You identify with folks whose stories sound a little similar.

I have that same feeling about Jackson C. Frank, the singer-songwriter from the '60s. Your new album "Loving You" is with Bobbie Nelson. How did that come about?

That came about when I was recording "Take it Like a Man." I was considering putting [Willie Nelson's] "Always On My Mind" on there. It fit the story, I guess . . . We tried it at the studio there [in Texas], and I thought, "I think that it'd be really cool if we tried with Bobbie."

We went down there and tried it. Me and Bobbie had such a good time making music without having to even communicate, really. We had a lot of fun, but it was just so easy. Then we were like, "We're going to start a band." We started a record, and first song we cut for it was "Always On My Mind." The second song was "Summertime."

When we decided to make a record, I was also thinking about how important her story is, not just for Texas music, but for women and for all music.

How did you first encounter Bobbie and her music?

When I was young, I saw her playing with Willie Nelson. This was in my 20s or 18. I was playing a lot . . . I saw her, and I thought, "Who is that?" Because I was standing in the back, and she had a cowboy hat on, black, not just being a supportive side. Her piano playing was effortless and wizard-esque. She was the only proof for a long time that I saw that you could be a sideperson and be a woman.

It was much later I saw Cindy Cashdollar, and it was Cindy Walker that I saw at her 70th birthday party where I thought, "Oh, women can write songs."

You do a lot of different projects, which I appreciate. You have "Loving You" coming out. Your album "Take It Like a Man" recently came out. You have the bands that you play in, your super group: the Highwomen, and the 400 Unit. How do you balance all that? How do you balance, especially the band work with the solo projects?

Well, truthfully, and luckily I stumbled onto something that is my happiness and is my joy, but it's also, secondarily, I'm really not good at anything else.

Now, I know that's not true because I know you're a painter.

You have to have a place to exercise a part of your brain that's feelings but wordless. You just like to do something – and see a result from it it. Because you make music, and you play it, and there's the music meditation where we're all in this wonderful place together, like a symbiosis and connectivity . . . But you can't visually see it. You take it in.

Amanda Shires and Jason Isbell in "Running With Our Eyes Closed" (HBO)You have to have places to put the feelings, and sometimes, you to have more than one place because there's a lot of feelings. You perform sometimes with your husband, Jason Isbell, and you've been very open about the struggles of marriage, which I appreciate. Is it hard sometimes to leave it all backstage, and then go onstage and perform no matter what might be going on behind the scenes? Or, do you bring those feelings into the performance?

Amanda Shires and Jason Isbell in "Running With Our Eyes Closed" (HBO)You have to have places to put the feelings, and sometimes, you to have more than one place because there's a lot of feelings. You perform sometimes with your husband, Jason Isbell, and you've been very open about the struggles of marriage, which I appreciate. Is it hard sometimes to leave it all backstage, and then go onstage and perform no matter what might be going on behind the scenes? Or, do you bring those feelings into the performance?

Oh, sometimes it gets into the performance, but that hasn't happened in a while. We've come to a place where we've talked about a lot of the problems that get wrapped up in the personal versus the work, which is a different kind of personal. Like I said once upon a time to him, maybe when COVID was easing up, as a way to go forward, I said, "I'm a sideperson when I play with you. We need to put this out there, and I am able to put that in a box, our marriage stuff, for the work and the time, and you just have to trust me that I can do that."

"It was just that I needed to learn how to quit, learn how to stand up for myself. To say, 'You can't say that.'"

Of course he does, but sometimes just verbally saying those things that you know the other person knows – you just like to reinforce the fact that I can separate this . . . That helps a lot because unless you say it out loud, you can assume it, but you need to hear it, and you need to say it. You need the other person to know it's OK to be the boss because their name is on the sign . . . I want his work to be what it is, what he wants it to be. Now, in my own band, I expect that same thing in return. Even in the studio, after having had that conversation, it's been easier. Your name's on the sign in the studio when it's your recordings, and mine's on the sign in mine, so you just sit down and listen and try to do what I want you to do. He's never been a sideperson, but he's learning how.

You also have talked about how you support each other in writing songs, often personal, very open songs. Do you ever veto songs from each other? Like, I don't want you to write about this, or this one's too much?

No, I think we've never vetoed a song. I think we're more concerned with making good work. And so, when we get to trouble spots or decide we want help, then we ask, and we show each other our work. Sometimes, if we don't want any help, we'll just say, "I wrote a new song. Listen to it."

Now, that wasn't always the case, and during "Take It Like a Man," I was writing that, and we were in a horrible spot. I sent him "Fault Lines" because we weren't really talking even though we live in the same house, and he didn't even listen to the thing . . . But we crossed that hurdle. It's a hard thing. They say marriage is hard, but sometimes it's hard. We had gone through it one time, and I've heard people say it can happen four or five times . . . We do comment and try to help if we see help, but if I hear something of his that just needs a lot of work, or I'm not buying it, I just straight up have to tell him. Just because sometimes you need to know. And I want him to do that for me. Who else is he going to show?

And it's an important level of intimacy too, to be able to share a creative work with someone.

And it's difficult. It's hard to hear. It's hard for me to hear sometimes, "Oh yeah, you're missing the whole chorus here," or something. Or, for him to hear, "Your tone is changing throughout, and it doesn't really match what you're trying to say." It's hard to hear criticism, but I think we've learned how to do it in a kind way.

Do you hope your daughter goes into music?

No! She has such long fingers, I think, and she has such an amazing brain. I realize my mom was always, "Have a backup plan." So I always had a backup plan – and it's not easy. It is beautiful, beautiful people, beautiful experiences, but I would hope for her to do something more stable. But I don't think that's going to happen. She went to Lubbock last week and started writing a song about prairie dogs.

It's happening.

"I've got to get you to quit." I had this feeling a long time ago . . . She was playing the kazoo and poking around. I thought, "Oh, no." And that's the catalyst for The Highwomen, how I started that idea. On a long drive when I was still in a van, I was thinking, "What's the worst that could happen? She could make friends and have happy experiences out there," And I was like, "Oh s***, there's not enough room for women." The worst could happen, right? It could be country music because there's pop, it's more level – but it all feels really rigged a lot.

That leads into something I wanted to ask you, which is that you've talked about how you almost quit music. Why did you almost quit, and what brought you back?

I didn't have agency, I guess. I'd been kind of beaten down a lot in the studio with various scenarios, various recording projects . . . When you start as a kid, and you have this beautiful thing: you've been making music, and it's glorious. You don't know about the other things about when you go into the studio. Just how awful people can be . . . I guess they just forget the fact that they're working with humans, and it can just be abusive.

I'm not saying that there's physical abuse. It just didn't feel good. I thought, "Why do I keep doing this to myself? What does that say about me?" I started blaming it on myself and saying, "Oh, you must like that kind of treatment," and all this. But in the end, it wasn't that at all. It was just that I needed to learn how to quit, learn how to stand up for myself. To say, "You can't say that," or, "You can't do that," or, "That's not a nice way to talk to a person," or, "I'm not taking that anymore. I'll leave."

"Your voice is shaking or trembling, and you think, 'Oh God, this isn't how I want to be strong.' But it's a practice. There's an art to doing it over and over."

This is all while thinking: I still have to pay my bills. But you just have to get up and say some stuff. And then, a lot of things politically happened that help give you a voice as a person who's grown up before we were allowed to say a lot. Like 2017 with MeToo and people listening and all that has happened since, where we are allowed to not lose our jobs because we want to say something that might sound bad to you.

I had to learn to try and just say stuff and then use my words, as I tell [daughter] Mercy. I had to have my feelings and be OK with the fallout, whatever it might be – and all those things are just some hypothetical what-if's in your mind. I'm not super great at being verbal. That's why I'm a writer and musician, but it sucks sometimes to be trying to say something, and you're not used to saying things, and your voice is shaking or trembling, and you think, "Oh God, this isn't how I want to be strong." But it's a practice. There's an art to doing it over and over.

That happens to me too, and I also cry more than I want to cry. I never want to be crying, but I'm always crying.

I can be saying something – and so much of it is how people take it in, or you're thinking too much about what other people think. And then you're: "Now I feel this thing, and now I'm going to cry." It happens to me all the time, and I always cry.

You have a lot of bird imagery in your songs, and I see you're wearing your hat today with wings on it, and you also wore wings when you performed for "Take It Like a Man" sometimes.

Birds don't cry.

That we know of.

Exactly. They've got it all, man.

So birds are important to you?

Very important to me. I don't even eat birds, I love them so much. I have 10 chickens. I've had them since 2017. A couple of them met their early demise via foxes and whatnot, but I still have [chickens]. They're still fantastic, good friends. Birds, they operate on different planes, land and sea or land and air, and they have this different model for how they not only parent, but live as individuals together. They even have the right to decide if their eggs are viable, and they can just push them out if they want. We don't even have that. We're not allowed to do that.

I was reading today about Aid Access . . . They were started in the Netherlands, and the woman in the article was saying that there were 1,500 calls for prescriptions a day coming from the U.S. alone. It's just a wild time.

One of the things that I've always appreciated about you is that you're not quiet on things that matter to you.

I'm not quiet, but my voice still warbles. I need, what's that lesson you get when you can make your voice be lower and stronger, and then people listen?

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

If you could go back in time and meet your 15-year-old self — you had just heard Bobbie Nelson, maybe, you were joining the Texas Playboys – what advice would you give yourself as a teenager?

I would say first, don't be so hard on yourself, and next I would say . . . Don't go rope swinging. You'll break your finger. Don't go rope swing in 2011. And I would tell myself, you don't have to be everything all the time.

"Loving You" with Amanda Shires and Bobbie Nelson releases June 23.

Shares