As a scientist studying exoplanets, Aomawa Shields, Ph.D., has spent her career searching for life on other planets. On her way there, she carved her own path on this one.

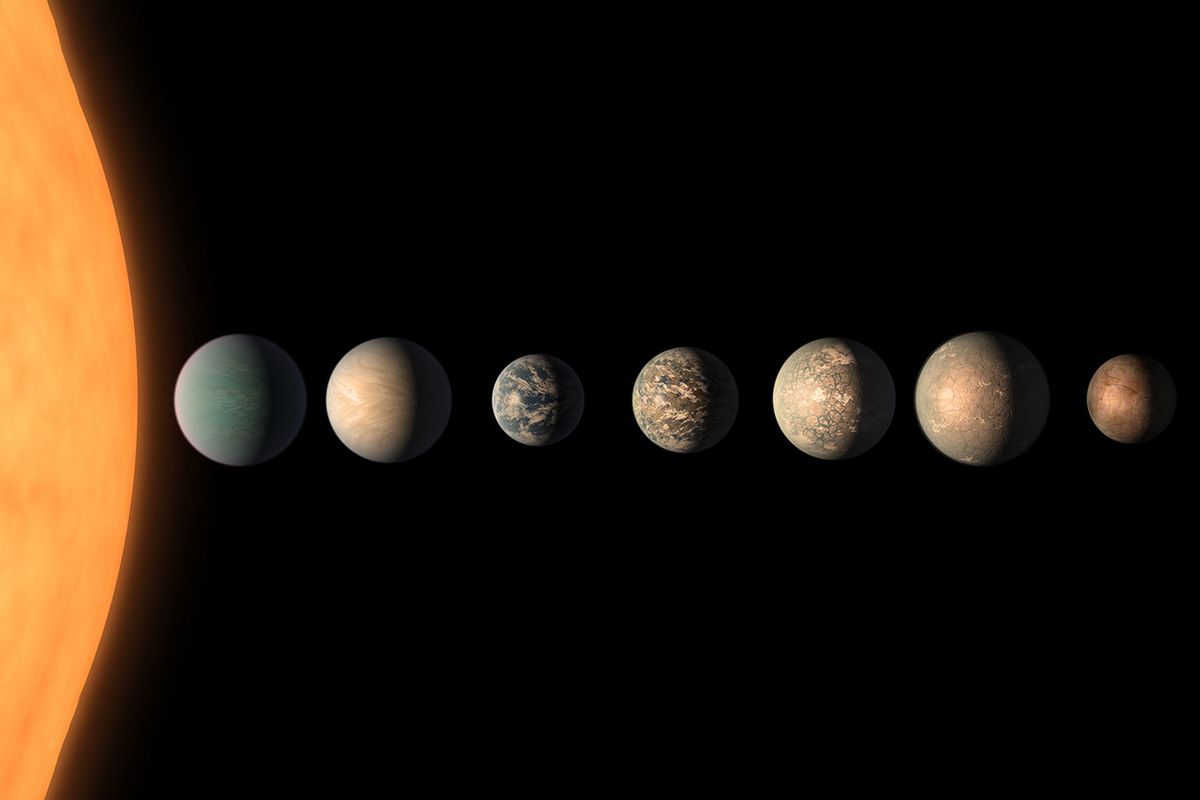

Shields' research focuses on finding life on exoplanets, or those outside of our solar system. One of her most-cited studies detailed what we know about the habitability of planets orbiting red dwarf stars, which are smaller and cooler than stars like ours. Because red dwarf stars make up more than 70% of known stars in the universe, this opens up a world — or rather, billions of worlds — of possibilities for where alien life could exist.

Shields, an associate professor at UC Irvine, is one of only 26 Black astrophysicists in U.S. history. She is also a mother, a trained actor and a writer who recently published her memoir, "Life on Other Planets." The book details her journey to becoming a scientist and how she used her creative background as her "superpower," later combing these talents to create an educational program, Rising Stargirls, which teaches astronomy to girls of color.

Shields spoke with Salon about her path to astronomy, reconciling the creative and scientific parts of herself, and, of course, life on other planets.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

You discussed in the book a case of imposter syndrome taking root in your life during your time in school. How did you reconcile looking outward being a source of struggle to looking outward — like toward the sky — as being a source of wonder?

One of the main messages from this book is that there are a lot of opportunities to look outward in our lives. And I did for a long time: I looked outward in the sense of looking to other people to determine how I should feel about myself.

"It's very important to still have those people we can look up to. But if it doesn't exist, we need not think it can't be done."

I was so concerned with how I was appearing and the perception of me being an African American woman in a field dominated by white men. Being an older returning student, I was more than 10 years older than most of my peers in my cohort. And by this time, I had gone off and gotten an MFA in acting, so I had another reason to feel completely separate and apart.

But when I finally got that wonderful feedback from a mentor that my theater background is my superpower, that was this first invitation to turn inward, to see myself apart from how anyone else saw me, to really look at the gifts that I brought — that the things that I thought set me apart in a negative way actually set me apart in a very positive way, if I chose to see it that way.

I don't have any control over whether someone thinks I should or can be an astronomer or an actor, or both — whatever. But I have a lot of control over what I believe I can be, and what I believe is possible.

You also talked about being your own role model and that if you haven't seen someone do the things that you're doing before, that doesn't mean that it can't be done.

Absolutely. We get to be our own role models, and for a long time, I didn't understand that. It's important for there to be role models. I want to encourage and support the efforts that are at play to increase representation. It helps to see someone who looks like you doing what you want to do. It makes a big difference.

"It's not the work of the historically marginalized to make spaces more inclusive and welcoming for ourselves. That needs to be done by those who are in the majority."

The movies were the first gateway for me to see what was possible. It was like, even if people didn't look like me, they were doing these things that I wanted to do. But it would have been a whole lot easier if I'd seen more people looking like me in those roles.

It's very important to still have those people we can look up to. But if it doesn't exist, we need not think it can't be done. [I realized], "Oh, okay, I don't see this depicted a lot, or I don't see this as an example, but I want to do it. So I'm still going to do it, and I'll be the first."

You talked about how in your Ph.D. program, these outside forces, like discrimination and underrepresentation, crept in to make you doubt yourself. And you even said that your own mind became the "biggest racist" you had known. What needs to change in this "Ivory Tower" of academia to make a more inclusive environment for aspiring scientists?

I'm glad to see the conversation now moving to not only how do we get [Black and brown students into our departments], but how do we keep them here? And how do we keep them here, in a way that the quality of their life is high while they're here, so we move out of survival mode into a thriving mode? That's something that I've seen in my institution, and I hope that continues. Because it's not just about recruitment, it's also about retention and building in those support structures.

It's not that Black and brown students just aren't as interested in the sciences as white students. That's never been the reason why there are so few of us in these fields. It's because those support networks and systems that allow us to exist and thrive in the Academy, which has a history of systemic racism and white supremacy — that's part of our culture and history in this country — they have not been in place before.

"The hope is that that direct personal connection to what they're learning about will anchor them as they continue on in their astronomy and education."

I've always felt that it's not the work of the historically marginalized to make spaces more inclusive and welcoming for ourselves. That needs to be done by those who are in the majority, who recognize the importance.

Because those of us who are from these backgrounds are doing a lot of heavy lifting simply to be where we are and carry the history of our personal backgrounds, our legacies of combating oppression, our own imposter thoughts and all of those things. Then you compound that on to having to take on a five-year Ph.D. program and do all the things that people who don't have those burdens that they are carrying are doing. That's a lot. It makes thriving very difficult.

I think [this] needs to be accounted for in these departments when we're thinking about everything from how we approach setting up the support structures, to how we talk to the students when they are in our classes, whether they're struggling or not — having that awareness that they are carrying a load that is an invisible load to the eye, but it's extremely weighty to the soul.

Can you tell me a little bit about Rising Stargirls?

I thought, "How do I use my unusual creative arts background to inspire and encourage middle school girls of color to explore astronomy?" I had this feeling that that could be useful even before I went to the education literature. And then I went to the educational literature and found that there was precedent. When these creative arts activities are employed, girls of this age, their confidence increases, and [they start] asking and answering questions in the classroom.

Middle school is this critical age. It's been shown that between the ages of 10 and 15, girls start to get quiet in the classroom, they become really concerned with their physical appearance and less concerned with how they think and feel about the world.

"There are hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy alone and hundreds of billions of other galaxies. So the notion that it would just be us is, in my opinion, unrealistic from a probability standpoint."

[In Rising Stargirls], they're, of course, learning about planets and stars and galaxies and what constellations are. But they're learning about these things through a creative arts lens. So they're encouraged to bring their own personal backgrounds. They write poems and draw pictures of the planets and stars that they're learning about.

The hope is that that direct personal connection to what they're learning about will anchor them as they continue on in their astronomy and education, and hopefully keep them grounded as the heavy math comes in. Because no one can tell them that the poem they wrote about that planet or galaxy is wrong — you can't get it wrong in art.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

How did you use the tools that you developed in acting school in science when you returned?

I thought science was so objective that it didn't care about my feelings. When I got to acting school, it was all about my feelings. There, [I] was to bring up all those childhood experiences that were both positive and traumatic and have them right on the surface, ready to use to embody whatever the character needed. It's like all the emotions that I was expected to feel as these characters, I had to go back into my personal history to access [them]. So, at first, it was diametrically the opposite.

"It's a very real possibility that the life that we see out there is something that may not be able to talk to us. I would not consider that any less of an earth-shattering discovery."

What I know now is that, first of all, all of that vocal training serves me so well as a scientist. I mean, much of what we do during the day is talk. But in teaching, as an instructor, I'm talking to my students, and I can now key into the wonders of the universe. Because I have those feelings that I've been able to tap into through my acting training.

I think about those first moments of looking up at the sky, you know, and going back there. There was a wall that I think I had that existed. And I don't know if this exists for other scientists who haven't trained as actors. But I'm glad that one doesn't exist for me, that I'm able to share that wonder and awe with students pretty easily and they pick up on that.

How confident are you that life on other planets exists?

Well, it's hard for me as a scientist to extrapolate or predict in terms of a confidence level. What I have now is a hope — and I will go in further to say a belief without proof, but a belief — and that belief is that we are not alone. I always think about Jodie Foster's character in the movie "Contact." … Her character says, "If it is just us, it seems like an awful waste of space."

I believe that. There are 10 to the 22 stars within our observable universe. So it's hundreds of billions of stars in our galaxy alone and hundreds of billions of other galaxies. So the notion that it would just be us is, in my opinion, unrealistic from a probability standpoint.

However, there are those who subscribe to the idea that our earth is rare … that certain circumstances and compounds and molecules and the energy source all conspired to allow life to arise on our planet and that is a rare occurrence. It's certainly a hypothesis that's worthy of consideration, too. But I keep coming back to, if it is just us, given the sheer numbers out there, it would be such a waste of space.

Do you think we'll find confident evidence of that in our lifetime?

There was a time when I remember being at conferences, and people were talking about the James Webb Space Telescope that was on the horizon. And there was skepticism about whether JWST would actually be able to do much for Earth-sized planets.

Yet, just in January, we confirmed the presence of an Earth-sized planet with James Webb. And those scientists are looking at trying to use James Webb to determine the atmospheric composition of that planet. So it seems like our instrumentation capabilities are exceeding our expectations. And that leads me to believe that we have every potential to be able to learn a lot about the habitability of these new worlds, maybe more quickly than we think — perhaps within the next few decades, perhaps, if not in my lifetime, then within my daughter's lifetime.

What might it look like if we found evidence of life on other planets?

The majority of life on this planet is microbial. And if we think about the cosmic calendar that Carl Sagan shared all those years ago and how humans came on the scene on December 31, we can see how such a small part of history humanity and humanoid life forms have been. It's a very real possibility that the life that we see out there is something that may not be able to talk to us. I would not consider that any less of an earth-shattering discovery.

"If there is a liquid on that moon, the liquid [wouldn't be] water. It's ethane and methane, so if there's anything swimming around in there, it would be life as we absolutely do not know it."

We could find life within our own backyard, within our own solar system. The moon of Jupiter, Europa, has an entire ocean under its ice crust. We're sending spacecraft back to drill and see if there's anything swimming around in that ocean.

There's Saturn's moons Enceladus and Titan. Enceladus and Titan are very different. Enceladus has a liquid water ocean and these geysers of water spewing out from the south pole. Titan, if there is a liquid on that moon, the liquid [wouldn't be] water. It's ethane and methane, so if there's anything swimming around in there, it would be life as we absolutely do not know it.

So I am excited, even though in my mind, I'm like exoplanets [are] where we need to look. But there are the vast astronomical distances with exoplanets that we would have to contend with.

My team did some really exciting work this year to look at what would happen if you have a planet that's around an M-dwarf that's synchronously rotating, which means there's a perpetual dayside, perpetual nightside and only habitable surface temperatures along the terminator — that dividing line between. We got to see that that scenario is possible and more likely if the planet has less water on it.

One of the things I love most about my work is being able to propose hypothetical situations that could sustain life in a planet system and knowing that those planets could actually exist out there. We got to see that this scenario is possible.

We need your help to stay independent

Who did you write this book for?

I dedicated the book to myself as a young girl and to my daughter. In many ways, I suppose I wrote it directly to speak to those two little girls.

However, when I think about the readers of this book, I think it's for everyone. It's for people who have always had a dream that they never pursued, or they pursued it for a while and then they had to do something else because they had to support their families or because it didn't seem practical or, for whatever reason, life happened and they abandoned that dream and they think it's too late. I wrote this for them.

"They might feel like those magical unicorns but there are other unicorns in the meadow. This is the story of one that they can sort of use as a companion to then create their own path."

I wrote this for people who have multiple interests, whether it's two, three or five. And they're not sure how to combine them and they think they have to figure that out. As you can see, reading the book, I tried to figure it out and chose one and then chose the other and was trying to figure out this perfect recipe. It was when I stopped figuring it out and simply embraced it, accepted it and allowed the universe to show me how to combine the two — that was when miracles started to happen.

I wrote this for people that are parents who are struggling to combine work with family and want to have a sense of their priorities and honor them rather than the priorities of someone else.

And I wrote it, of course, for people from historically marginalized groups that are inhabiting predominantly white spaces, whether in academia or business or other fields and they feel alone. I wrote it so that they know that they are not. They might feel like those magical unicorns but there are other unicorns in the meadow, as I wrote in the preface. This is the story of one that they can sort of use as a companion to then create their own path.

Shares