Even before the Disney Pixar vehicle "Finding Nemo" turned a pair of clown fish into popular ocean-dwelling protagonists, these distinctive orange and white fish were adored for their charismatic coloring and habit of turning venomous sea anemones into their apartments. These qualities have made clown fish (Amphiprion ocellaris) some of the jewels of home aquariums but these flashy bars serve a purpose beyond looking festive.

"The white bars could be an important color pattern for distinguishing competitors for territory in anemonefish."

Now a new study in the Journal of Experimental Biology offers an insightful clue into why some of the 28 described species of clown fish have white bars on their bodies in the first place — and in the process, their research demonstrates that the fish are even smart enough to count.

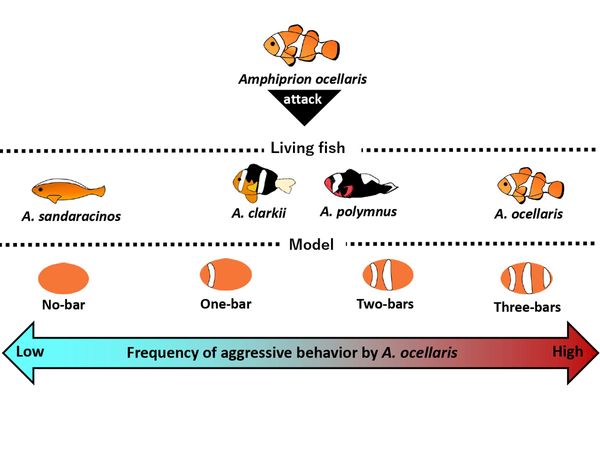

The experiment in question involved 120 individual A. ocellaris fish, which typically have three white bars on their bodies. The fish were then provided with opportunities to interact with model fish that had varying numbers of bars on their bodies. As this happened the scientists noticed a striking pattern. The real-life fish behaved more aggressively toward models with three bars than any of the other models, and as much so as they did against other living A. ocellaris.

They also showed considerable aggression (Nemo can be very territorial) to other clown fish who had only two bars, which is consistent with the developmental biology of young clown fish, which start two bars before growing a third. These aggressive behaviors in themselves make sense, since the researchers observe that clown fish will inhabit a host sea anemone for their entire lives and "fiercely" defend it as their territory. Yet what is striking is that the 120 clown fish reacted differently to other supposed fish based on the specific number of bars they sported.

Figure showing the aggressive behavior of Amphiprion ocellaris, or clown anemonefish, in response to different species of anemonefish, both live and models. (Kina Hayashi)

Figure showing the aggressive behavior of Amphiprion ocellaris, or clown anemonefish, in response to different species of anemonefish, both live and models. (Kina Hayashi)

"We conclude that A. ocellaris use the number of white bars as a cue to identify and attack only competitors that might use the same host," the authors conclude. "We considered this as an important behavior for efficient host defense."

The experiment has its limitations. Foremost among them, as the researchers pointed out, the 120 clown fish were raised in a controlled environment where they had only ever seen members of their own species. As such, it is unclear whether the aggressive behavior to other fish is innate to A. ocellaris or acquired due to their domesticated upbringing. At the same time, previous experiments have suggested that clown fish use the white bars to identify both each other and different fish species.

The authors point to field experiments conducted by Japanese scientists in the Ryukyu Archipelago, during which A. ocellaris behaved aggressively much longer with models that had white vertical bars rather than models with white horizontal bars. Those researchers theorized that the clown fish behaved this way because their colonies are prone to being invaded or intruded upon by fish species like damselfish, cardinal fish and wrasses, all of which have various horizontal stripe patterns but no vertical bar patterns.

"Amphiprion ocellaris may therefore recognize fish with bar patterns as competitors and frequently attack and chase them out to defend their host anemone," the authors explained. "These previous studies indicated that the white bars could be an important color pattern for distinguishing competitors for territory in anemonefish."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter Lab Notes.

Immature clown fish "exhibit more frequent aggressive behavior toward their own species than toward other species, and differences in the number of white bars caused differences in the frequency of aggressive behavior."

The scientific community is divided on whether fish overall are intelligent, which challenges pop culture assumptions that these things are nothing more than dumb animals that "don't have any feelings," as Kurt Cobain once put it. But that perception is changing. In a 2014 article for the journal Animal Cognition, Macquarie University biologist Culum Brown argued that the existing scientific literature suggests fish are more intelligent than popularly acknowledged.

"The review reveals that fish perception and cognitive abilities often match or exceed other vertebrates," Brown wrote, before adding with an eye on the question of animal rights that "a review of the evidence for pain perception strongly suggests that fish experience pain in a manner similar to the rest of the vertebrates."

Brown later concluded that "the extensive evidence of fish behavioral and cognitive sophistication and pain perception suggests that best practice would be to lend fish the same level of protection as any other vertebrate." By contrast, a trio of Swiss and Dutch scientists published a 2022 study in the International Journal of Behavioural Biology which argued that ectotherm vertebrates — that is animals like fish, reptiles and amphibians — have brain structures which make them inherently more intelligent than endotherm vertebrates (animals like mammals and birds).

We need your help to stay independent

"Endotherm and ectotherm vertebrates may process cognitive tasks in fundamentally different ways due to differences in brain organisation," the authors argued.

While the researchers behind the clown fish study did not elaborate on the intellectual abilities of their subjects, they argue that at the very least clown fish can count as high as they need to in order to ascertain the number of bars on potential rivals.

"It is thought that A. ocellaris attacked more frequently 2- and 3-bar models in this experiment than no-bar and 1-bar models because during their developmental stage they have often seen individuals with 2 or 3 bars as competitors," the authors write in the study. They concluded that, as a result of their experiment, they know that immature clown fish "exhibit more frequent aggressive behavior toward their own species than toward other species, and differences in the number of white bars caused differences in the frequency of aggressive behavior." If nothing else, clown fish are smart enough to read visual patterns and use them to distinguish between other individuals in their own species and among other fish species.

Read more

about fish

Shares