As the son of a drive-in theater manager, actor Matthew Modine grew up watching movies. “I always enjoyed films that were about problem-solving,” he told me on "Salon Talks." “And I never wanted to play bad guys. I didn't want to be the person who was causing problems . . . I wanted to be a person who was providing a solution.” Ideologically, Modine believes that actors have a personal responsibility for impacting people’s lives. And he lives it. Citing Native American sensibility, he notes, “What we have to do all the time in our lives is think and to try to look at [the] totality of our decisions, the things that we do.”

That sensibility is at play in every role he takes. Nearly 40 years ago, he passed on the lead role of Maverick in "Top Gun," which eventually went to Tom Cruise and was the highest-grossing domestic film of that year. He found the story’s focus on “war pornography” disturbing, he said. “I didn't want to be in a movie that perpetuated this idea that 'those people are bad and we are good.' And 'We're right, you're wrong.' I just thought the whole movie was silly.” Modine's more recent roles, like Vannevar Bush (the scientist and creator of the Manhattan Project) in "Oppenheimer," can be hard to square with his stance on nuclear power. While he was honored to portray Bush for director Christopher Nolan as an important part of history, he balanced it by executive producing a documentary called “Downwind,” about the lethal effects of nuclear testing on American soil.

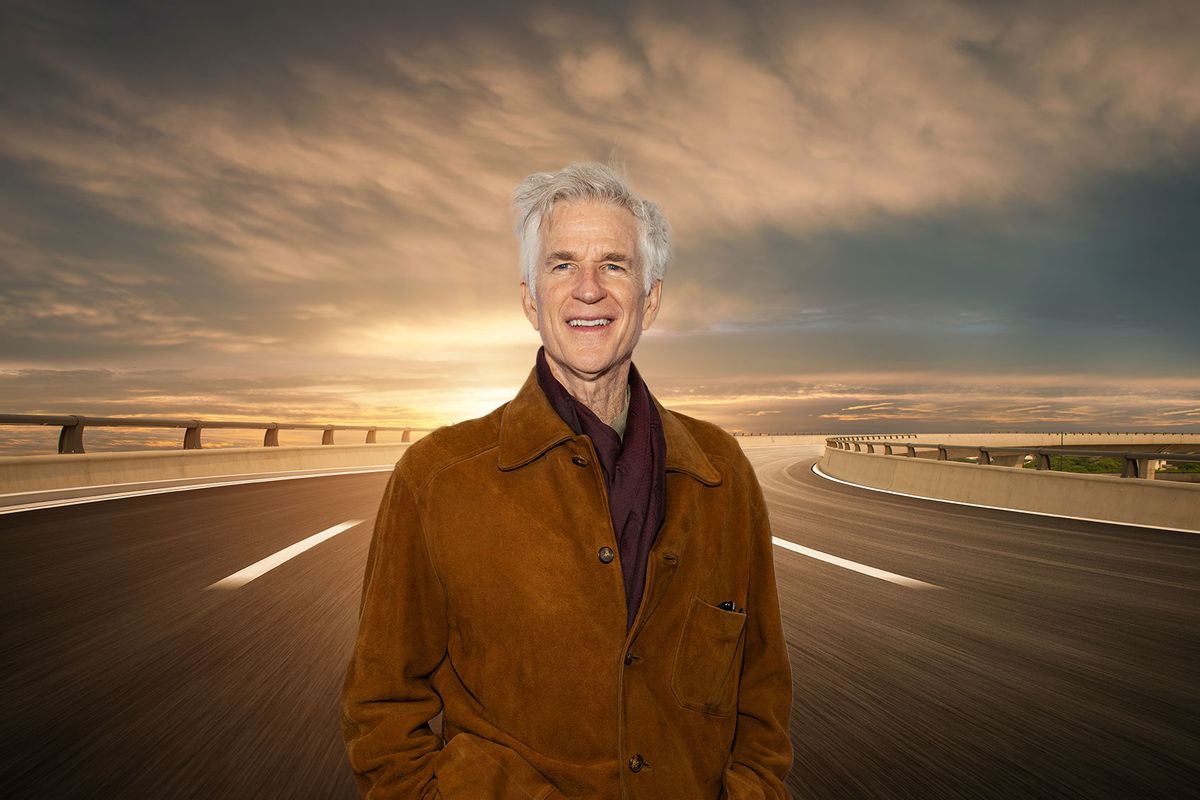

Modine has been living what he advocates for many years as an environmentalist and also riding bicycles since he arrived in New York City as a struggling actor (he relied on a beach cruiser to get to auditions). So when his latest film "Hard Miles" (in theaters April 19) came along it had strong appeal: overcoming adversity, solving problems and cycling as a metaphor for freedom. Modine plays cycling coach Greg Townsend on a 760-mile bike trip that he rides with incarcerated students from Colorado’s Rite of Passage’s Ridge View Academy (a medium-security correctional school). Cycling from Denver to the Grand Canyon, the characters — based on real people — struggle mentally and physically, learning many life lessons. "It's always about how much you're willing to push yourself," Modine said of the journey.

Watch my "Salon Talks" here on YouTube or read our conversation below to hear more about why Modine believes so strongly in building a career that reflects his personal values and politics and why he thinks his "Stranger Things" co-star Millie Bobby Brown and her fiancé Jake Bongiovi (the son of Jon Bon Jovi) asked him to officiate their upcoming wedding.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Did you ride here on your bike?

I didn't. No, I just finished work, so it was a short walk from the New York Public Library over here.

Tell me a little bit about your character Greg Townsend in "Hard Miles."

It’s based on a true story. Greg Townsend worked at this academy. He's a bicyclist. And he got the idea that what if I was able to teach these young people how to build bicycles so that they would create something that they would be proud of, that they would have their input and their life put into the building of a bicycle, that they'd be proud of the thing that they created. And then what if I took them on an arduous ride so that they could see that the world is bigger than the troubled home that they came from, that they could see that the world's bigger than the gang that they were a part of before they ended up in this facility?

"I never wanted to play bad guys."

If you're looking for a visual, imagine the horse that has the blinders on, and he's not able to have any peripheral vision. He's just able to see this part of the world. And so what Greg was able to do was to take them out into the world and help them expand their vision, to help give them peripheral vision, and see that there's much more to life than the little problems that are consuming them in their actual lives.

And the real Greg Townsend, tell us about him.

Greg was there for most of the filming. He always rode his bike to work. And there were some extraordinary . . . When we were in Northern California up near Mount McKinley, not only did he ride about 30 miles to get to the location, but he did a vertical mile to get up the mountain to the location. And he'd get up there and not even breathing hard.

How old is he now?

He's about 60.

I'm so impressed.

Yeah, me too.

“Hard Miles” is a journey film and a triumph over adversity film — physical and mental. This is the story of these real hard-luck kids. They are juvenile offenders sort of given a second chance, but not valued or validated except by your character, and perhaps the social worker who's along for the ride. She's a great balance for you in the film.

She really is, yeah. You needed her. Cynthia [Kay McWilliams] is a wonderful actor. And she grounds the story. Without her, I don't know how the story would've worked. It'd be very different.

We need social workers to help level the field of some of these emotional reactions.

Absolutely.

You've been a cyclist since you were 18, coming here to New York as an impoverished actor. I've read the story about you getting a beach cruiser to ride around New York to your auditions. “Hard Miles” is set in Grand Canyon Village, 6,000-something feet above sea level, and these roads are no joke. What was your training like for the film?

The training was on-the-job training because there wasn't a lot of time from the time that the boys, the younger kids in the film were cast to going on location and filming. They were sort of training on the job. And doing hard miles. The movie is appropriately titled. And you do a take and they say, "OK, let's do it again," and you have to ride back and do it again.

So, we did a lot of miles in riding up and down the mountains and, "Let's do it again." And then I think the hardest thing was when we rode through the Navajo Nation, and just at the rim of the Grand Canyon it was 115 [degrees], and the heat coming up off the blacktop made it even hotter. The agony that you see as we're pedaling through that long, long road through the desert, there was no acting involved. You just had to put your head down and go and push.

That's crazy. I did a road trip Arizona through Diné, actually, territory, and Navajo in August. It's brutal out there.

Yeah, it is brutal.

There are a lot of metaphors in this film, among them that life can be uphill and feel like a challenge for anyone. What does cycling represent for you in real life?

Well, bicycling is one of the most tangible ways of explaining democracy. When the suffragettes were fighting for the right to vote, the women were not really allowed to drive carriages. They weren't allowed to ride horses, but there were no rules about the bicycles, so the bicycle became a symbol of freedom for women's rights and women's equality. I think that's amazing.

But I think that for young people today who are so caught up in their phones and social media, the thing about a bicycle is that if you want to be present and in the moment, ride a bicycle, because if you're looking at your phone when you're riding a bicycle, particularly around a place like New York City, you're just asking for trouble, you're asking to get hurt.

"That's what film and television and theater has the potential to do — to help make the monsters go away, to illuminate."

The bicycle is a tool for consciousness and awareness and also a kind of meditation that, especially on a hard ride where you're going through the desert . . . And we show that in the film the kind of nightmares and memories that people start to go through as they're suffering. And it's a sort of way of sweating those things out of your body. I made a movie a long time ago called "Vision Quest," and there I think are similarities in the journey that Louden Swain goes on in "Vision Quest" that echo the journey that these kids go on. In wrestling, you're always wrestling against yourself. You're seeing how far you're willing to push yourself. And I think when you're part of a Peloton, riding bicycles, that it's always about how much you're willing to push yourself to be able to discover your personal strength and vulnerabilities.

Well, those who know me know I couldn't agree with you more, that cycling is therapy for me and it really is a way to sort of get everything out. And it's meditation, if you understand it. You have a very long history in TV and film. What draws you to these kinds of triumphant stories?

I suppose my father was a drive-in theater manager, and I grew up watching movies. And I always enjoyed films that were about problem solving. And I never wanted to play bad guys. I didn't want to be the person who was causing problems. I wanted to be a person who was providing a solution. There's so much suffering in the world that why wouldn't we want to go and learn about people that are reducing that suffering and finding solutions to problems that make our lives better? I'm attracted to those kinds of stories.

I know because of that background of the drive-in theater and seeing how movies and television affect people's lives, that when you come into people's homes on a television, when you're projected onto a motion picture screen larger than life, when you stand on a stage and do a play, the things that you do and the things that you say will have an impact on people's lives. I absolutely respect that, that people are going to be impacted. And so it can be a tool of propaganda that is detrimental to society, or it can be something that . . . My grandmother used to say that, "The room is full of monsters when it's dark." And she said, "It only takes turning on the light to make the monsters go away.” That's what film and television and theater has the potential to do — to help make the monsters go away, to illuminate.

In 2020, you told Salon's Chauncey DeVega that you have chosen, "in my personal life to be on the right side of history." Can you explain what that means to you today?

I'm reading a book right now called “The Pursuit of Happiness.” And Benjamin Franklin was someone who kept slaves, George Washington was someone who kept slaves, and they all recognized that it was a cruel and inhuman thing to do, but they all appreciated the luxury and the convenience that came with owning another human being to do things that you didn't want to do. Now, I think that Benjamin Franklin is one of the brightest, most moral people in our nation's history and the fact that he recognized, the fact that he was doing something that was wrong and cruel, but so he did get on the right side of it. Abraham Lincoln was for slavery until he was against it.

"What are the repercussions of the decisions I make today? What will they have on people that are not yet born?"

What we have to do all the time in our lives is think and to try to look at the circumstances in its totality of our decisions, the things that we do. So, I'm an environmentalist, and I do everything that I can to be on the right side of that history, to leave the world a better place for my grandchildren and my great-grandchildren. They say that we don't plant trees for ourselves, we plant them for our great-grandchildren because we will never enjoy the shade of those trees. So that kind of Native American wisdom that that story comes from, the planting trees for our great-grandchildren, that's where that seventh generation comes in.

I actually have a production company called Seventh Generation Stories. It’s the same concept, which stems from the conservation philosophy from the Iroquois Confederacy, the First Governance. It says that you should always leave things in a way that will be better for seven generations living afterward. And it's why in indigenous culture it's auspicious to have a centenarian and an infant alive at the same time because it doesn't happen that often. So, it's a beautiful way to live. I try to live that way. Sounds like you do as well.

I try. What are the repercussions of the decisions I make today? What will they have on people that are not yet born? We live unfortunately in the United States that I don't know that we're even a democracy anymore, we're a corporatocracy and we're making decisions that are based on financial gain. And with eight billion people on the planet, it's unsustainable. We can't make decisions that are just based on finance and profit. It won't work. We're consuming the Earth's resources at an unsustainable pace.

You have shown in your film choices over the years that the personal is political by turning down roles that became huge blockbusters. Examples include Maverick in “Top Gun,” Marty McFly in “Back to the Future,” and Charlie Sheen's character in “Wall Street.”

I did, yeah.

Are you sorry about any of those choices?

Marty McFly I would've loved to have done. But Eric Stoltz is a dear friend of mine, and they had let Eric go. He was playing the part, and then they said, "You have 24 hours to make a decision about replacing him." And I wanted to know, "Why did you fire Eric Stoltz?" That didn't make sense. But in fact, I can't imagine a better actor than Michael J. Fox playing that part. I'm 6’3.

Can you fit in a DeLorean?

[Laughs]. And this is not to make Michael J. Fox small, but there's something about . . . If you think of a Jack Russell and a Labrador, let's say that it needed a Jack Russell. And Marty McFly and Michael J. Fox, he was that Jack Russell. Michael J. Fox in that movie is always on the front of his foot, leaning in, ready to fight.

He was relentlessly attentive and determined.

So, I didn't turn that down for political or philosophical reasons. I just didn't see myself playing the role.

But “Top Gun,” absolutely. I didn't want to be in a movie that perpetuated this idea that those people are bad and we are good. And we're right, you're wrong. I'm right. I'm smart, you're stupid. I just didn't want to be a part of something like that. I just thought the whole movie was silly. It was what I would call war pornography.

There's plenty of it.

People like war pornography. There's a big market for it.

You mentioned your environmentalism. You executive produced a documentary called “Downwind,” released last year and narrated by Martin Sheen, that chronicles the lethal effects that nuclear testing has had on American soil, and specifically on U.S. citizens who are downwind from toxic chemicals. Many of them are indigenous people in the Southwestern states. So, tell us how you square our own politics with playing roles like the brilliant nuclear scientist that you just played in “Oppenheimer,” Vannevar Bush, creator of the Manhattan Project.

Well, to be invited to be part of the ensemble of Christopher Nolan's “Oppenheimer” was a great honor. And it's the second time I've worked with Christopher and his wife Emma. They're incredibly talented, gifted storytellers, and so it was an obvious honor to do it. And then a bunch of actors that I hadn't worked with that I really admire, including Matt Damon. Robert Downey [Jr.] and I started out in the business at the same time, so it was nice to reconnect with Robert. I'm really pleased for him and all of the success that the film brought him. Cillian Murphy, I'm just a great admirer of him, and he lived up to everything that I hoped that he might. He was extraordinary, and such a gentleman, so Irish in all the best qualities of being Irish. A poet. He really is a poet.

But that's an important story to tell about . . . When I started kindergarten in San Diego, Imperial Beach, California, we were still crawling under our desk, doing duck and cover drills, and it was frightening. I remember very vividly, there was a song that came out, "The End of the World." And of course it's a love song, but to me . . . I remember asking my older brothers, "Does this mean, because crawling under the desk, that the end of the world is near?" And they terrified me and said, "Yes, of course." And then the Vietnam War happened, and all the instability that comes to a child through those kind of horrors. Death and destruction seems so imminent.

Always. And even more so. It continues.

So my brother Maury, he's the one that got me really involved mentally about the Downwinders. I was watching the news and he was being arrested on CNN, handcuffed. And the microphone came pushed into his face, and they said, "Why are you protesting?" And my brother said, "They know they work. Why do they have to test them?" And I think it was the most important simple statement ever made, that since the Trinity Test that Oppenheimer covers, why did they need to keep testing them — especially after dropping them on human beings twice in Japan, in Nagasaki and Hiroshima that caused the death and suffering of hundreds of thousands of people? So, why do we need to keep testing them? And there's no logical explanation for why they need to keep testing them. And they're talking about starting it up again, and testing them in our near future.

I have memories of not being able to drink the milk when Three Mile Island had leaks here in New York when I was a kid. I think most of the past few generations have had some experience, unfortunately, with this awareness, this fear of being poisoned to death.

I was in England when Chernobyl happened. My wife was nursing and they said, "It's not a problem unless you're a nursing mother," which my wife was. Because the radiation gets in the breast milk. And yeah, it's a real nightmare. It's a real nightmare.

Last question, I'm going to throw one away for the Gen Z-ers. It’s been widely publicized that you're going to officiate "Stranger Things" castmate Millie Bobby Brown's wedding. Yes? How did this come about?

She asked me. She must have talked to Jake, and they had a conversation. And I honestly don't know how it happened, but it's a great honor. I had married a dear friend of mine during COVID. It was an outdoor wedding. It was extraordinary when you think that people are coming together that when you say, "Dearly beloved, we are gathered here," it's "we" – it becomes a kind of beautiful spiritual gathering of people . . . because this is not an arranged marriage, this is a marriage of choice, and there's something that's beautiful about that. To be the person who gets to officiate, and to join those two people, and give them some, I don't want to say advice, but share some thoughts about the journey that we can make together as human beings, I'm really chuffed that they asked me to be the guy that does it.

And where can everyone see "Hard Miles"?

It opens on April 19th at 600 theaters across the United States, so I encourage you to go see it in a movie theater because it's really beautiful. The photography is stunning. And it's just fun to go be in a room with a bunch of people and experience a movie together. Quite different than watching a movie sitting on your couch and being disrupted by your phone. Going to a movie theater, having grown up with my father's drive-in movie theaters and movie theaters in Utah, there's nothing like it. It's better to go to movies with people and watch it together.

Shares