Nothing is fair. The meritocracy is a myth. Bad things happen to good people.

Most of us pretty much know this already. Yet we are also instinctively hopeful, can-do creatures, who like to think that if we can just crack the code somehow, we can prosper and avoid suffering. For some, that wishfulness takes the form of vision boards and dog-earing “The Secret.” For others, it’s striking bargains with God.

Kate Bowler is a Duke Divinity School professor with a Christian background. She was also, until recently, perhaps best known as an expert on prosperity gospel teachings and author of a book on the subject called “Blessed.” Then in 2015, at the age of 35 and with a young son, she was diagnosed with Stage 4 colon cancer.

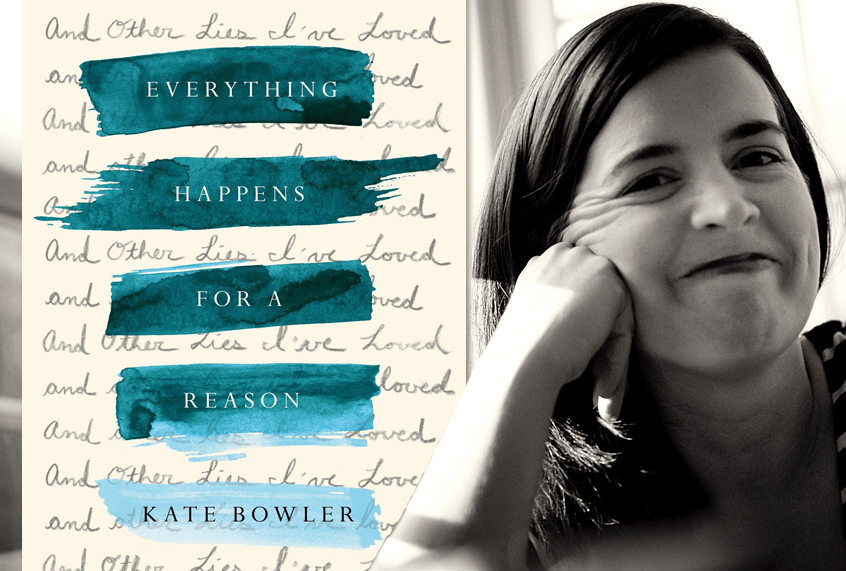

Today, Bowler is still alive, cautiously surviving on treatments including immunotherapy, and has a new memoir of her experiences with the down-to-earth title “Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved.”

As a fellow Christian and member of the Stage 4 club, I was eager to devour Bowler’s book as soon as I heard about it. We spoke recently via phone about God, grace and what prayer can — and can’t — give you.

You studied prosperity gospel, you’ve written about it a lot. But you yourself never pushed all your chips in towards the prosperity.

No, I didn’t. I’m a naturally reluctant person to rush in with judgment. I did try for over a decade to fully understand empathetically the kind of worldview that makes the prosperity gospel possible. Like the idea that we’re all living under an open heaven and anything that if you pray for and hope for it the right way, it can be yours. Sometimes I found it absurd. Sometimes I found it exploitative. But it was too easy to say just that because everyone has the caricature of the weeping televangelist in their minds.

This book was kind of a theological excavation project for me. I thought I was just trying to render a world plausible in which someone could be that, I guess, arrogant to hope for all and expect all these things. Then the second I got sick I felt, “Wow, maybe I was just like them all along. Maybe I always thought that my life was something I could orchestrate.”

It’s not just about Christianity. There’s this pervasive idea of manifestation; that you’re going to vision board your way into or out of something.

I was part of my own multilevel marketing presentation! The way I’ve been thinking lately is that every day is full of possibilities and inevitabilities, and you don’t know which are which, right? This lie I was trying to abandon, that the whole world relies on me, quickly became exaggerated in cancer world. All of a sudden, I have to like fight like hell to be in the right place at the right time in order to get the right treatment. I just kept not learning that lesson over and over again because it was so useful. It’s one of the book’s useful lies, like, “I am in charge of all things. Just give me the keys.”

It’s almost easier when it’s your own story, because when it’s someone else’s, you want control and you have none.

I think everyone in pain is probably narcissistic to some degree. I’m just realizing that I really only saw the world from my perspective. I’ve been learning. Now I’m starting to notice what my parents must have been going through and what my husband must have been going through, which is a sense of exaggerated hopelessness and helplessness.

My dad, he’s very careful with his words. From second one, he just refused to cry about it. He refused to imagine that I would not be healed. That was a lifeboat for me, when I needed somebody to not move into helplessness, especially when they just can’t fix me. I’ve borrowed that confidence all the time. Maybe the next round of drugs is going to be really effective. But for everyone else, I think it’s really hard to know what to feel when you generally have no control over something that’s just about to destroy your life too.

It’s so surreal.

That is the word. Very often I just felt, and feel like, I’ve been floating above. I think that the things that define most people’s lives, like the breakfast to eat, and the decisions they make, all that seems like it was part of a normal and rational word that I no longer lived in. I was living in this surreal word where I was part of these decisions partly that I was making and mostly other people right before me that would determine me no matter how I felt about it. Almost all the major things, all the things that would largely decide if I live or die, are things that I don’t get to choose. That’s not how I see myself, right? I see myself as like at the beginning of a decision tree. I make the decisions.

Once you go through something like this, it’s like a certain veil has been pierced about the illusion of how much control you have over your life, and how much control you have over your future.

I almost took it personally. The part that would make me cry is that I thought, “Man, I guess I really did think I was special.” I couldn’t believe that cancer didn’t care about who I was. All the things I’ve chosen to love — my beautiful, perfect, absurd kid, this man I loved for a million years — it just didn’t care. I couldn’t imagine myself being able to surrender every good thing for this thief, this poisonous juggernaut that was headed my way.

It’s so hard to reconcile that, to feel like, “Well, wait a minute, but I’ve been good, I’ve done all the right things.”

I just decided that there are impossible things to give up. Those are the most beautiful ones. I just decided that if God was going to come close to me in the midst of that, it could not be to ask me and pretend to be benevolent about it, no way.

You talk about that so much in the book and you talk about these unhelpful things that people say to you. People will say “Well, I’m praying for you.” I’ve really had to step back and ask myself, “What does that mean? What are you praying for?” What is your understanding of faith? When you are praying for something, what does that look like?

Well, I’m praying for miracles, which is to say the interruption of the world order. I’m praying for good science and healthcare coverage for everybody. I’m praying for both rational and irrational things, because I really do believe that part of prayer is about the dignity God gives us to have enough arrogance to ask. I think that’s just part of love. God loves us in our particularity and knows that we want. I think we’re allowed and encouraged to ask for particular things. Of course, there’s a difference between being able to ask and being able to expect. But I just go for it, I really do. I pray for complete healing.

I don’t mind when other people pray for those things too. In fact, I started to get really grouchy at some of my more liberal friends because I feel like, for them, prayer was an exercise in manageable expectation. I mean, “Dear God, I hope for just vaguely nicer things.” I’m like, “No, no, this is the worst. I need you to put your back into it right now. Don’t give me vague hope.” It felt a lot like love to hope for the most for me, but without me having to then carry the burden of responsibility of explaining why it didn’t happen. It’s not my burden to bear that there are theological conundrums. I don’t know, it would be great if you can figure it out, but it’s actually not my job right now. My job is to live, to figure out what hope means and learn to live after certainty. That’s my job. If I can learn from other people, amazing. But part of that is watching them learn to hope with me without them forcing me to have lived some kind of formula that was supposed to work out.

I often want to just pull out all the stops, ask the universe to just rain down massive miracles. Yet, I also have to pray for the grace to deal with whatever happens. To find God in my community, to find God in the people who hold me up when I feel like I can’t stand on my own two feet.

It’s so basic and it’s so supernatural at the same time. That’s how my experience of God is. It’s in the very, very everyday acts of people who took me to the airport so I could fly to get my treatment and brought me food for a year and were not embarrassed to be afraid with me and pray for me in such gorgeous ways. Their gift of God’s presence was so very ordinary, but it was so beautiful.

I do feel like I have been humbled. People surprised me with how gracious they were and I didn’t realize how much I needed them.

That really is where the grace is and that’s where I find God in all of this, running parallel with science. To me, they’re never in conflict and I don’t have to choose.

So, the Prosperity gospel is not the same thing as Pentecostalism. After I got sick, I loved the joyous prayers of Pentecostals. Here’s what I learned from them: They are not worried about the time. I heard when other people prayed for me, it was very polite and took about 22 seconds. The truth is I was in so much pain physically, emotionally, everything. It was nice when people would just linger with you. They just stay put, and they will pray for you until you’re done, and they don’t care what time it is. That was lovely, and that was the kind of prayer that feels wraps you up in much better spiritual bubble wrap before it pulls you back out into the world. One of strengths of this Christian community is prayer without formality, prayer without — and I mean it in the best way — dignity. They don’t care, they’re just in it.

I want to ask about how we have to really change the conversation around cancer in general. How do we stop looking at it in terms of “cured” and look at this as a long-term condition that we’re managing?

This is partly why I’ve been trying to ask people to stop calling me “terminal.” It really hurts my feelings! It’s because we have this thin vocabulary from where we are right now and hopefully we’re moving to a point where cancer can become a manageable illness. But in the meantime, ask everyone to find a different statement than just “cured” or “dying” because I know I’m neither. I think of it like I’m swinging vine to vine, like I grab on to one vine in immunotherapy and then hopefully one just moving me from one good outcome to another. It will require a different imagination and a different way to set horizons. Instead of imagining an unlimited future, learn to hope for another good thing and then just saying, “It’s not perfect, but it’s enough.”

There’s so much in this world that I cannot change. What is possible today? I ask myself that every day. It’s the only way I can balance the idea that everything is inevitable and that everything’s possible.

This conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.