There is widespread agreement that the global rise of authoritarianism over the past few years was partly the fault of social media. In organizing nationalist, right-populist, and even outright fascist movements across the world, different sites played different roles. YouTube and Instagram were a powerful organ for propagandizing children and teenagers. Facebook replaced the commons, but in doing so, it balkanized much of humanity, hermetically sealing its users in groupthink bubbles and delivering increasingly inflammatory content to keep them hooked. Reddit, the digital equivalent of a meeting hall, for years was hesitant to ban its far-right subreddits on grounds of promoting free speech. And all of these sites, in their eternal quest to encourage users to spend as much time on them as possible, used algorithms designed to encourage users to find other rabbit holes of content similar to what they liked already.

Things changed after Trump — and to a lesser extent Bolsonaro, Duterte and Brexit — won at the ballot box, and many of Silicon Valley’s CEOs had a come-to-Jesus moment pondering their role in our global authoritarian political moment. Hence, for the past year or two, these social media sites have begun widespread purges of their far-right, white nationalist and pseudo-fascist users. The term “deplatforming” refers to when social media sites restrict or ban users with repugnant views, restricting their abilities to either radicalize or monetize. Most tech companies balked, initially, at public calls to deplatform certain noxious users; but following persistent outrage, the techies finally heard the masses: we don’t want fascists on our platforms, or anywhere.

The astonishing thing about deplatforming is that it works: early alt-right darling Milo Yiannopoulos has been reduced to penury, now unable to make a living off of his poison pen by sites like Patreon, YouTube, Twitter and so on. The same goes for reactionary conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. There is empirical evidence that deplatforming reduced the number of people coming to them for ideas.

There are still many corners of the internet where authoritarian and right-nationalism reign supreme, and where people with those views organize. Still, if deplatforming is beginning to have an effect — and if Facebook and Twitter are suddenly more wary of the potential for their platforms to be used to manipulate — the logic would suggest that as more authoritarians and fascists are deplatformed, the global tide towards authoritarianism might slow down, or even cease.

There is not any evidence that this is happening, nor that there is much of an effect on more significant movements. Hungary continues its slide rightward; Turkey has devolved into an authoritarian state, and Brazil’s newest president Jair Bolsonaro is about as right as they come in democracies.

Of course, Silicon Valley is not the only vehicle for the far right; authoritarian movements predate social media by a long shot. Still, the global love affair with nationalism and authoritarianism has led me to wonder if perhaps the ability of social media to spread right-wing viewpoints comes about not merely from social media propaganda, but from the way that content itself is propagated online. More specifically: what if the slide towards authoritarianism has to do with the form of social media, more so than the content?

The trickle-down politics of tech companies

Sociologists have long pondered the relationship between the media we consume and our political beliefs. This is difficult to suss out, as the relationship is not always one-to-one: violent video games, for instance, don’t seem to make people commit more acts of violence, though there is some evidence they make us more aggressive.

Other forms of media seem more manipulative, empirically speaking. Social media can induce moods in people: depressing content makes people sadder, and positive content happier. Consumers become more narcissistic as they spend more time on social media. That makes sense on the surface: humans are social creatures, so it makes sense that being immersed in a culture of selfies and self-promotion would make one feel that they have to behave the same way.

Troublingly, an increase in narcissism among the young and the decline in global support for democracy could be connected. A 2018 study found that U.S. and Polish citizens that were more self-centered expressed less support for democracy. From the Pacific Standard:

…people with higher levels of narcissism were more tepid in their endorsement of democracy. Specifically, they were more likely to agree with statements such as, “Democracies are indecisive and squabble too much” and “Democracies aren’t good at maintaining order.”

Not surprisingly, people who held right-wing authoritarian views (measured only in the American sample) were less likely to endorse democratic values. But even after that mindset was taken into account, narcissism was still associated with lower support for freedom-based, representative government.

It is intriguing to me that narcissists are less supportive of democracy, and that narcissism is one of the traits associated with authoritarian leaders — indeed, it is a trait that is celebrated by authoritarians’ followers. Likewise, Trump was perhaps the finest example of a narcissist who leveraged social media to build his following.

And speaking of Trump, how and why was he able to get away with how he built his following? Trump leveraged the free publicity machine of Twitter to build a following that many would regard as at least demi-authoritarian in nature. He built a cult of personality around himself. And he was able to do all of this because of the structure of Twitter itself.

Meet the influencers

Silicon Valley is not exactly an exporter of democracy, as many of its luminaries reveal. PayPal co-founder and billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel has railed against democracy as incompatible with freedom, and even gleefully analogized tech companies to dictatorial monarchies. Still other techies in his circle form the crux of a growing movement of techno-authoritarians, people who work in or among the tech industry and believe that monarchies or despotisms are the best way to rule over people. Perhaps the hierarchical nature of tech companies, and the CEO- and founder-worship problem in Silicon Valley has led some techies to locate their politics in that lens as well.

Though perhaps it is unsurprising that some techies would turn authoritarian, as we know of other instances in which the organizational structure of institutions often begets their politics. As I’ve written before, the anarchic desert canvas of Burning Man was easily gentrified and remade by rich people because it never had any egalitarian guarantee from the start. If there are no rules from the beginning, nor regulations, those with the most power and the most money reign supreme, as they have the greatest ability to shape a landscape.

Nowhere is this truer than in the world of social media. Anyone can gain a social media following, but it’s easiest if you have money — to promote your content to others, to vet your tweets before they go out to prevent you from saying anything too inflammatory, and to spread your message widely through the magic of PR firms. The landscape of social media is already deeply classist in this sense. The people whose views you are likely to stumble upon are more likely to be the rich and powerful (This is oddly analogous to American politics: a vast study of American elections, often cited by Noam Chomsky, found a linear relationship between which congressional candidate raised more money and which one won).

The landscape of social media is in no way a democracy. Even the way that social media sites structure themselves promotes a sort of top-down approach to existence: Twitter and Instagram profiles prominently list one’s “followers.” Not one’s “coevals” or “co-equals,” but followers — a telling word that recalls cults. The language implies that Instagram and Twitter consist, then, of leaders — the people who dictate down to us, the lowly followers.

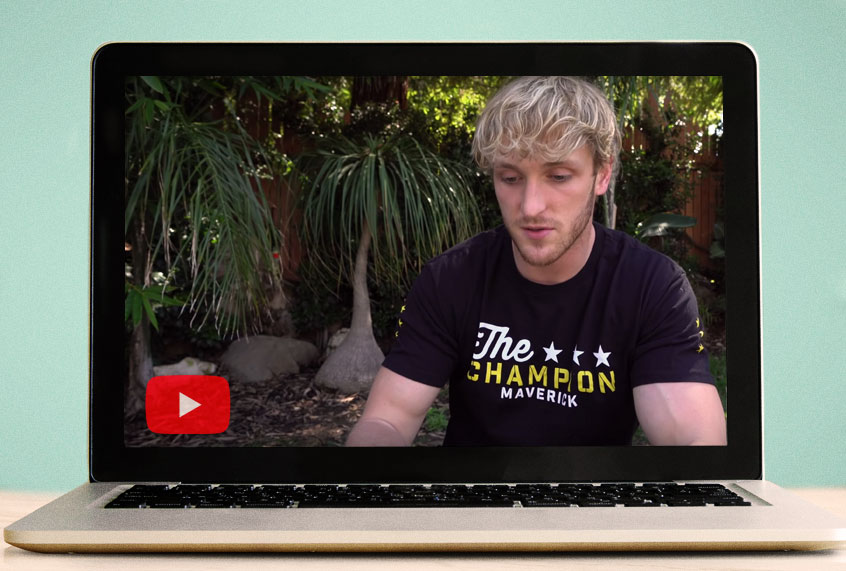

The dystopian term “influencer” has gained mainstream acceptance over the past few years, and means, roughly, a postmodern celebrity whose fame derives from their celebrity. Marketers seek out sponsorships with influencers to help sell their products out to the influencer’s followers. Influencers often do nothing other than look as though their lives are enjoyable, which is the point of image-centric social media sites like Instagram and YouTube. The idea sounds inane to older generations, but the youngest generation reared on these sites, are obsessed. Parenting blogs are rife with accounts of children who become addicted to YouTube; a British marketing study claimed that around 17% of 11- to 16-year-olds aspired to be “social media influencers” when they grew up.

As influencer culture attests, the entire structure of social media is top-down, an organization of leaders and followers, the kings and the peons. Many critics have written off social media as the ultimate tool of neoliberal culture, a vessel for hyperindividualism that encourages all of us to see our humanity as fully monetized. You can see how the more hierarchical aspects of social media might also lend themselves to authoritarian thinking, too. (Not that neoliberal economic policies and authoritarianism are mutually exclusive, but they can exist separately, too.)

We, the followers, aren’t finding space on Instagram or YouTube to work together and build solidarity movements. It’s simply not designed to do that, at least not easily — and that’s not what makes these companies money.

Social media is designed to encourage us to strive to become influencers, leaders whose ideas will be believed by virtue of our follower counts, who will be listened to and paid attention to merely because our popularity is a self-reinforcing feedback loop. It sounds an awful lot like authoritarianism, albeit with a faintly egalitarian twist — anyone can become an elite if you just monetize well enough and get that follower count up.