Secret files found on a longtime Republican operative’s computer after his death revealed that he compiled racial data to help his party draw new political maps and impose voter ID laws.

Thomas Hofeller, who is considered the master of modern gerrymandering, left behind at least 70,000 files that were found by his estranged daughter after his death in August 2018. Some of those files have already been used to successfully challenge North Carolina’s gerrymander and the Trump administration’s plan to add a citizenship question to the census, which Hofeller argued would help “Republicans and non-Hispanic whites.”

More files, obtained by former Salon editor David Daley at The New Yorker, show that Hofeller and his race research played a key role in Republican gerrymandering efforts in North Carolina and other states, as well as other efforts intended to make it harder for African-Americans and college students to vote.

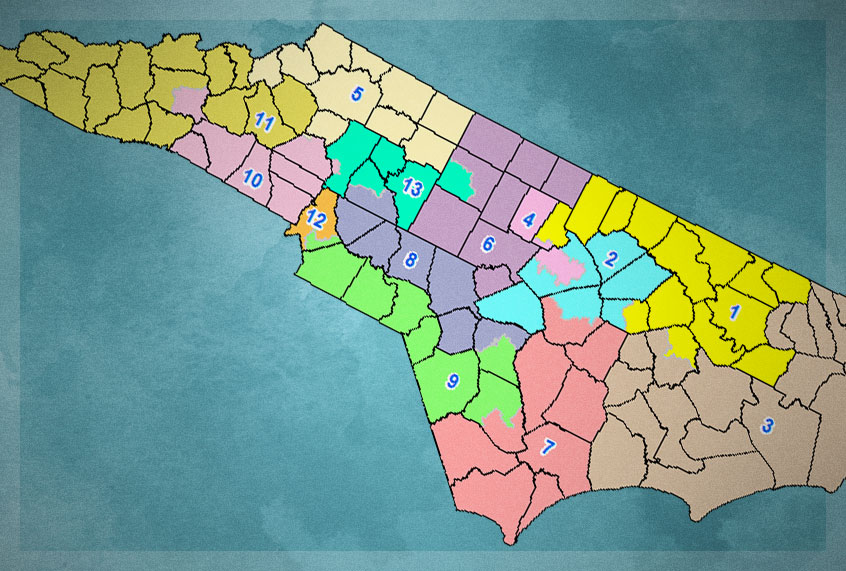

Though North Carolina Republicans have argued that their maps discriminate based on partisanship and not race, Hofeller’s files show that he compiled maps with overlays of the black voting-age population by district, suggesting that racial data was a key part of the gerrymander, which is at the center of a years-long legal battle.

The files contradict claims Republicans have long used to defend their maps in court. Republicans had long denied that a congressional-district line that cuts right down the middle of the largest historically black college in the United States, North Carolina A&T State University, was intentionally drawn to dilute the black vote, even though it effectively guaranteed two Republican districts. But Hofeller’s files show that the effort clearly focused on the race of students.

Hofeller created “giant databases that detailed the racial makeup, voting patterns, and residence halls of more than a thousand North Carolina A&T students,” Daley reported. “He also collected similar data that tracked the race, voting patterns, and addresses of tens of thousands of other North Carolina college students. Some spreadsheets have more than fifty different fields with precise racial, gender, and geographic details on thousands of college voters.”

A spreadsheet found on Hofeller’s computer shows that the operative sorted students by the residence halls they lived in along with racial data and voting status information.

Hofeller also had dozens of “intensely detailed studies” of the racial makeup of North Carolina college students that was cross-referenced with driver’s license files to determine whether these students likely had a proper ID to vote, according to the report.

Emails on his computer also show that Hofeller billed North Carolina Republicans tens of thousands of dollars for his work. Federal Election Commission filings also show that the national Republican Party paid Hofeller more than $2 million for his work.

Other files show that Hofeller, a key player in the Trump administration’s push to add a citizenship question to the census, compiled data on the citizen voting-age population in North Carolina, Texas, Arizona and other states going back to 2011. In memos, Hofeller argued that drawing maps based on the number of citizens rather than the population would “clearly be a disadvantage to the Democrats” and help “non-Hispanic whites.”

Hofeller also submitted memos to the Trump administration urging them to justify the census question with the dubious argument that it was necessary to enforce the Voting Rights Act. The New Yorker report shows that he also worked for a Massachusetts Republican who wanted to use the Voting Rights Act to turn Boston into a single district, so Republicans could contend for suburban Massachusetts congressional seats. Though Hofeller’s efforts were unsuccessful in Massachusetts, the files show he also compiled data on states like Virginia, Mississippi and Alabama.

Emails found on Hofeller’s computer also show that he advised top Republicans in Florida on gerrymandering effort, despite a state constitutional amendment that bars partisan gerrymandering. Florida officials have denied that Hofeller played any official role in the effort but a state judge later ruled that the Republicans “conducted a stealth redistricting operation that snuck partisan maps into the public process and made a ‘mockery’ of the state’s constitutional amendments,” The New Yorker reported.

The files show that Hofeller also traveled around the country to educate Republicans about redistricting and urged them to push for prison gerrymandering, which allows inmates to be counted as residents of the area where the prison is located, often helping Republican lawmakers.

Hofeller’s emails also show that he grew concerned that his maps would be undone by the anti-Trump wave that followed his election.

“Meanwhile the GOP continues to bury its collective heads in the sand or in other higher places. Trump is only a product to this stupidity,” he wrote to a Republican consultant in 2016. “Do not worry about us in North Carolina in terms of redistricting. Even in the coming political bloodbath we should still maintain majority control of the General Assembly. The Governor cannot veto a redistricting map, so the Democrats hope is that the Obamista judiciary will come to their rescue.”

Last week, a North Carolina court struck down the state’s legislative maps that Hofeller helped create, ruling that they violated the Constitution. The new map had been drawn after the Supreme Court struck down North Carolina’s previous map as a racial gerrymander.

The court ruled that Hofeller’s maps “deliberately minimized the effectiveness of the votes of citizens with whom they disagree,” arguing that the map amounted to “viewpoint discrimination” against Democrats and an effort to “retaliate against voters” for voting for Democrats.

The court said that the files on Hofeller’s computer showed evidence of “predominant focus on maximizing Republican partisan advantage in creating the 2017 Plans.”

“The evidence establishes that Dr. Hofeller drew the 2017 Plans very precisely to create as many ‘safe’ Republican districts as possible, so that Republicans would maintain their supermajorities, or at least majorities even in a strong election year for Democrats,” the court said. “Hofeller drew the maps with an intent to preserve Republicans’ control of the House and Senate.”

The court gave state lawmakers two weeks to draw nonpartisan maps. Republicans have sued to try to get a court to seal or destroy the files, arguing that they should remain confidential because they were obtained from his daughter and not from him.

The files could be a treasure trove for voting rights groups as they seek to challenge years of Republican efforts to gerrymander districts in order to gain an unfair advantage, as well as to impose voter ID laws to make it harder for certain populations to vote.

“We’ve already seen that these files have been instrumental in exposing lies around the effort to add a citizenship question to the census and around subverting a court’s order to redraw gerrymandered lines,” Kathay Feng, the national redistricting director of Common Cause, told The New York Times. “The Hofeller files are important because they’re the only thing that will allow the American people to know the truth behind the efforts to rig redistricting and elections.”

The files show only a fraction of the work Hofeller did, which stretches back to the 1980s. Files obtained by The New Yorker show that Hofeller continued to work to help Republicans even after he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

“I still have time to bedevil the Democrats with more redistricting plans before I exit,” he wrote to a friend. “Look my name up on the Internet and you can follow the damage.”