The most recent unemployment numbers state that an estimated 26.5 million Americans are without a job due to the pandemic. Reports of overwhelmed food banks and shocking number (one third) of of Americans who didn't pay rent in April are reminders of how close so many Americans are to poverty, and how capitalism is failing those who live below the poverty line.

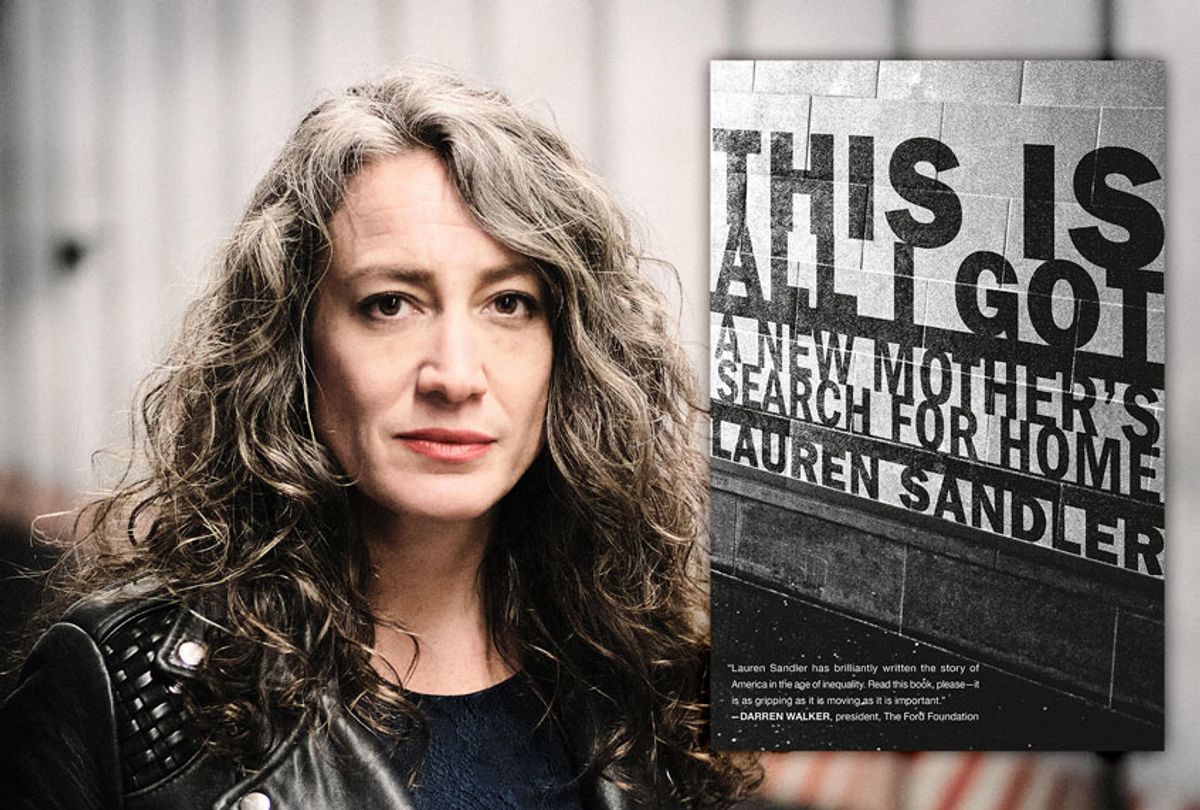

Yet if you haven't experienced poverty directly, there is only so much these data-driven stories and reports can tell you — which is why Lauren Sandler's new book, "This Is All I Got," is so powerful. A work of narrative non-fiction, Sandler follows Camila, a young single mother hunting for affordable housing in New York City. "Picture yourself at twenty-two with no margin for error," Sandler writes in the book. "Picture yourself shouldering the stress of caring for an infant while attempting to navigate the system." If picturing yourself in these shoes is hard, Sandler's vivid writing helps.

In reporting on Camila, Sandler transforms from journalist to friend, fostering a deep intimacy between the two that is evident in her reporting. Moreover, Sandler shows us that if Camila can't break the poverty loop, then nobody can. "What it means to get stable housing, not just in this city, but in this country, is something that is systemically impossible because of our policies," Sandler told Salon in an interview.

We sat down with Sandler to talk about the country's housing crisis, poverty, and privilege. As always, this interview has been condensed and edited for print.

Congrats on your book, I thought it was great. I wanted to hear more about why you wrote a book on homelessness and poverty. It sounds like you were disturbed by how the urgency of the poverty crisis has waned in the media over the last couple decades.

Homelessness is something that appalled people, that felt like a human rights crisis. It was a sign of our failed state, back in the '80s and early '90s. It's something that the [New York] Times covered once or twice a day on average, that was on the cover of magazines, as a true, true crisis.

When I moved to New York in 1992, over 20,000 people slept in New York City shelters. And it was considered an abomination, as it should be. I think that what has happened is [that homelessness became] something that people have grown accustomed to, and there has been an entire narrative that has been built around that. [That] is the ripple effect of Reagan. The narrative said that homeless people are homeless because they couldn't make it, and that we live in a country where everyone has a shot. I don't think that you need to do extensive immersion journalism to discover that that is shockingly untrue.

I think that another part of this is that we don't have a lot of stories of people who live in poverty. It doesn't mean that we have none. There's a golden age of journalism around doing this work. But it's expensive work to do, and it's hard work to do. It used to be that people would pay journalists to do this really in-depth, really sustained, character-driven journalism around issues like poverty. And as journalism has changed, so have our stories. Today, we learn about homelessness and poverty in general, mostly as big data stories, or big system stories. And that data is really important, but what happens when we don't get to enter what poverty feels like, how it's lived on a daily basis, there's a separation that's permitted there. And I think that that's an issue with our discourse around liberalism, as I think it's a lot easier for people who are separated from poor society to feel concerned because they read data stories about it. But they never really get to feel what it's like to live a different life. That's what literature does.

The storytelling of this book is such an important component. It's interesting though because Camila's life might not look like how people think poverty looks like. For instance, she's not living on the streets. And I'm wondering if as a journalist, as a writer, if it was important to you to tell a story about poverty that might look different to people who haven't experienced it before?

The majority of people who are homeless don't sleep on the street, at least in New York City. The majority of people who are homeless are single mothers with children. Yet we have the image of the guy on the bench, the guy on the subway. That's what homelessness is to people. The shaking coffee cup, the cardboard sign. That is not the majority of homelessness in America though. It's just simply the most visible one.

But we have a different crisis . . . . which is that one in 30 kids are homeless. And if you're a single mother, you cannot sleep on the street with your kids. I mean, there are some that do, but for the most part, that is not the choice that you can make. We have a large homeless shelter population and that shelter population is often made up of people who work as well — who you would not recognize as stereotypically homeless in any way.

When Camilla and I would go through New York City — and there's privileged me, next to Camilla and her baby who have just met up with me from the shelter, and we're taking the subway through New York — no one bats an eye that we are somehow separated. And it's not because either of us were dressed differently than we usually dress or acting differently than we usually act, there was just an assumption that, I imagine, that she's somebody who wouldn't be homeless. And that's the case with every woman who I knew in the shelter. The women in that shelter worked at Applebee's, worked at the Gap, worked as home healthcare aides.

You really immersed yourself in Camila's world, and she becomes your friend. What has that been like?

Yes. I mean, we have a complicated relationship. She and I go through periods in which we are incredibly close as I write in the book. I gave the toast at her wedding. I've been there as her friend and not as a reporter a lot. We really had the agreement that when the action of the book ended, I was no longer there as a journalist, but just as someone very close to her. But that doesn't mean that putting out a book about her isn't something to navigate. It's hard to be written about. Even if you have been a collaborator in the process. Not of writing and not of editing, but of, of course, inviting someone into your life.

And I think that if I had maintained very strict boundaries, the way that maybe other journalists would and hadn't become so deeply involved in her life, that might have been a simpler path. That might have been the notion of, "Thank you, got what I needed, going back to where I came from, and I wish you the best." But I think the part of why the book functions the way that it does, is there is really true intimacy between us.

And that was a very mutual thing and that's where we remain five years later. I haven't heard from her in probably four days and that is a while and that makes me anxious.

Your friendship and your intimacy makes the reporting so great. And I think it also, it shows it requires a certain vulnerability from you too, which I think is really interesting.

Oh, I love that you just said that. I've gotten some pushback from journalists, friends along the way about how I report. Not just for this book, but I think probably most radically for this book. I show up and I connect with people and not just in a journalist and the murderer way, but because that's part of why I do this, is because I want to deeply and authentically connect with people. I also think that that's what makes the work something that a reader can deeply and authentically connect with.

What role has your privilege played while reporting on her? How did you navigate that?

I mean, it's a huge central question. And as you can tell from the book, it's something that I have spent a lot of time thinking about.

I am aware that my privilege was always the unspoken element in every situation. She is a person who does not flag that difference. She's someone who tends to be really interested in closing differences instead of pointing out differences. And so it was not something that she would bring up a lot — which in some ways, was convenient for me, but in other ways, meant that there was, for me, a constant ethical undercurrent. It's something that I would bring up. I thought it was really important for me to acknowledge it constantly. But at a certain point, it felt like she was like, "Yeah, yeah. No, I get it. I get it."

She's one of these remarkable people who tends to make herself at least outwardly comfortable in so many different relationships and so many different environments. And so I think that she did that with me as well. And I felt it was my responsibility to be mindful of my privilege, not just in writing, but also just in walking through the world. And it was not her responsibility to be noting it at times.

Right. Yeah.

There's one thing I do want to add to it, which is, it is my privilege that lets me be a journalist. It is the fact that I graduated from college without student loans that allowed me to start doing work that didn't pay very well. And I also feel it has been my obligation as a person of privilege, to do work which is about people who live differently than I do. I think that there's been a lot of questions about who gets to tell whose stories? And that is a really important conversation to have. It is the conversation that I expected would be the main conversation around this book when it came out. That of course was before, the world fell apart for many more people.

Right. And "American Dirt" resurfaced this conversation recently.

I think it is important to talk about who gets to tell whose story and why. American Dirt obviously surfaced that issue most recently. And it got so much attention even though now that feels it was in a different world. I don't think that those were petty concerns of a different world.

I think it's important that we still continue to have these questions about identity and privilege and who gets to narrate history. Who gets to tell the story of how we live. And I would hope that my work is something that allows that. That the work speaks for itself. And then I have done it with a sense of calling and ethics that my privilege has allowed me to do.

Right, yeah. That all makes sense. Your book shows that it's incredibly challenging to get out of the poverty loop, even when you work hard and are determined. But for many, as we see in the book, working hard and having a sense of determination can be a source of hope. Do you think that hard work and determination is the only way out, if you're lucky?

No. I mean, it's hard to imagine someone working harder or being more determined or more organized or more tenacious than Camilla was. And it didn't matter. So anyone in that shelter would tell you that the most foundational need that they have is housing. There's a million other things that are needed as well. But without that most basic element of stability, the rest of it is impossible. And what it means to get stable housing, not just in this city, but in this country, is something that is systemically impossible because of our policies.

I was in a Zoom meeting with this guy who runs an organization for homeless outreach in Seattle. He's been doing amazing work there. And he said something that I really wish I had thought about on my own. But I just keep thinking about it and he said, "Everyone's so appalled with price gouging about hand sanitizer. Why is no one appalled about price gouging about housing?

That's a very good question.

I mean, it's so perfect. Of course, housing goes to the top bidder . . . . and if you can't afford it, then you don't get it. End of story. There's no notion that housing is a human right. There's no notion that this is something that should be regulated, that it should be fair in any way. And of course, what's happened is the real estate market has made housing an impossibility for people. I mean, a majority of people are rent-burdened.

I know, it's crazy.

It's crazy. So what is it that we expect people to work hard to do?

So [Camila] entered a lottery, to try to get affordable housing. And her name comes up in the lottery, and she still can't afford it because it's not affordable for people who are poor. We used to understand this, we used to know that housing vouchers were essential to give people housing security. We used to think that public housing was a really good solution to a really bad problem. And now those are things that just are impossible for people to access.

The notion that this isn't completely rigged, the notion that you can somehow supersede the extent of systemic injustice, unless you're born into a family that can help you do it, it's all just the inheritance game. And it is impossible. And it's a tragedy. And it's a tragedy that people don't see it.

The other thing that makes me crazy is how easy it would be to fix this. I mean, I've been watching as we all have, the bailout that's been going on, the stimulus package, and it's like the ability to just commit trillions of dollars. The number that most people have agreed on for years now to end homelessness has been $20 billion. $20 billion. So the amount of money that we just handed over to Delta and Ruth's Chris Steak House, I mean, it blows my mind, how if we wanted to fix these problems, we could. And frankly, if Mark Zuckerberg wanted to fix this problem, he could write a check. If Jeff Bezos wanted to write a check for $20 billion, he would still have $90 billion.

Shares