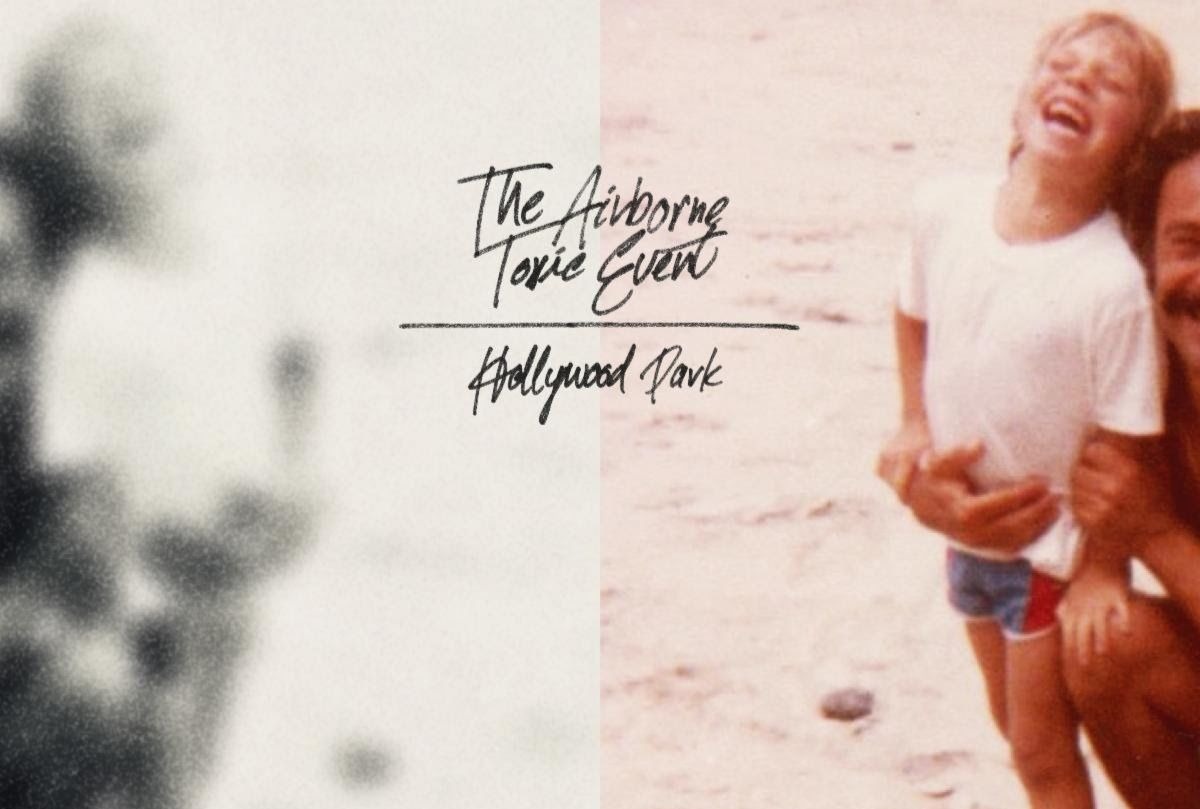

On May 22, the Airborne Toxic Event released “Hollywood Park,” their first album since 2015’s “Songs of God and Whiskey.” The Los Angeles band, led by Mikel Jollett, has always favored music informed by moody ’80s alternative music, cinematic indie rock and the artistic grandeur of acts such as David Bowie. The majestic “Hollywood Park” — which boasts spacious arrangements, dynamic guitar swells with orchestral flourishes, and Jollett’s emotionally weathered baritone — is no exception.

Lyrically, the album “Hollywood Park” follows the thematic arc of Jollett’s memoir of the same name (out May 26, Celadon). The book is an absorbing, emotional read: In the book, Jollett navigates his complicated relationships with his mother and older brother; reconnects with his father; and digs into the deep, long-lasting reverberations he experiences from living in (and then escaping from) the infamous cult Synanon.

The memoir “Hollywood Park” came together over the course of several years. Jollett spent five to six days a week writing the book. He’d rise at 5 a.m., write until 10 or 11 a.m., and then edit for an hour or two before turning to reading. “I have to read every day or else I can’t write,” he says. “I usually read four or five hours a day.”

To inform his writing, Jollett also visited different places that appeared in the memoir. “Toni Morrison has this wonderful idea about re-memory and how memories exist in the places where they occurred, so you can go back to those places and they’re right there,” he explains. “And I found that to be true.

“I’d sit and take notes or speak into like a tape recorder, and get everything that I was thinking down — sights and sounds and things and every new memory that came rushing back. It’s like a string you keep pulling on.”

Jollett spoke to Salon about the Airborne Toxic Event’s return, how his memoir came together, and why bands such as The Cure and The Smiths meant so much to him growing up.

You started writing songs about half a decade ago, and then your book just grew out of it. How did this start? What was your process?

When my dad died, I was really floored by it all — just really sad. I had been on the road for a long time. I told the band, “I need a break from everything.” It’s not romantic to talk about in interviews, but I was just depressed. I don’t know how else to put it; it was a depression.

Being on the road for so long — you’re always up, you’re up, you’re up, you’re up — [and then] next thing, you’re up, you’re up, you’re up, next thing. And it was a combination of things. I mean, the biggest, of course, being my father’s death. I became unhinged for a while and just didn’t leave the house.

You know, I didn’t expect how big a deal it would be. I don’t know if you’ve ever had anyone close to you die, but it’s really disorienting. I knew it would be sad, because he was sick for a long time. And I didn’t really expect how much it would be confusing. It was just confusing. Like, “What are we do now? I don’t understand; how can he not exist? It’s like saying water doesn’t exist.” It didn’t compute.

It took me a long time to process it all. I started writing songs; I was trying to capture what was going on. It was almost like I needed the music like I had always needed music.

Lewis Hyde is a guy who wrote this book called “The Gift,” which has been really influential for my life and as an artist. He has this thing where, basically, the idea is, it’s better when there’s some mystery, when you don’t really know why everything that’s happened has happened, where it all comes from or why you’re doing it. I don’t know why it felt good to write super-sad songs when my dad died, but it did.

I could take some guesses, but the truth is it just felt good to get lost in it and fully feel it and really embrace it. So that’s what I did. And, after awhile, I decided I wanted to write a book. That was also just a very, very long journey, from about three years start to finish.

When you sat down to write the book, having the time for total immersion into it would also make a difference, I’d think — especially because everything is so distracting, you know between going online and everyday life.

Absolutely, like no social media on writing days, that’s for sure. [Laughs.] You’re drawn into the subjectivity of other people, and with writing you want to do the opposite. You want to try to remove all of that, and just focus on the thing you can concentrate on.

Being isolated and working down here — I have a basement office-studio that I built in my house here. I like a bunker. Some people like a view; I like a bunker. I like the feeling there’s nothing to look at but the thing I’m working on. Kurt Vonnegut always says, “Every writer needs an attic.” You gotta have somewhere that you go.

And the time is really important because so much of it was brute force. It was brute force of just writing and rewriting and writing and rewriting and writing.

Obviously, the story in “Hollywood Park” is just incredible, and as the book evolves, there are so many different threads that you realize, where in hindsight, you’re like, “I totally see that.” What revelations did you have as you were writing and sifting through all of these memories?

I came to respect how emotionally complex the world of children is. All kids, to some extent, feel like adults sort of dismiss them. But I feel like we really felt that way — like, the adults just weren’t listening to what we were going through.

Going back, those emotional memories are very strong. I think that’s true for most people. But as children, we don’t have words for it. We can only say, “I’m mad” — or sometimes we’re not allowed to say things like that, so we don’t say anything. But really what’s happening is you’re sort of mad, but you’re kind of sad, you’re a little bit angry at yourself. And you’re also confused and puzzled and a little disappointed in someone. That’s really more what it is.

And then how you experience it is you experience it, through symbolism and metaphor, because a lot of the world when you’re a kid you don’t really know what’s what. Especially when you’re very young. You don’t know if animals can talk. I didn’t — I didn’t know if animals could talk. I didn’t know if I could fly. I kind of suspected I could; for a long time, I thought I could maybe fly. Until I was about seven or eight. It was just a matter of believing I could.

This is going to sound really pointy-headed, but I came to understand that metaphor, as we understand it in fiction, isn’t something that lives in books. Metaphor lives in our lives, and lives within us, and it starts at a young age. And the fiction, or the story aspects of metaphor, they’re an approximation of this very real thing that exists in our brains, and not the other way around.

Not that we read or we watch stories to learn about metaphor — we make stories to try to approximate the metaphor, the imaginative world that we live with very deeply on a day-to-day basis.

When you describe hearing The Cure for the first time, and how Robert Smith was singing, he was really articulating something for you that you couldn’t quite understand, but you were drawn to it for some reason. I was also a huge music fanatic, but I didn’t necessarily think about, “Why was I drawn to this?” I was a big Smiths fan, too, but didn’t think about why the music resonated with me.

What was the first one for you? What was the first Smiths song?

My favorite song was “Hand in Glove,” but I always heard “How Soon Is Now?” first. Our radio station here played a ton of Smiths, so I was very spoiled.

You’re lucky. I had a friend who brought the Smiths into my world. It was “Louder Than Bombs.” I remember we went and bought it the day it came out. And then we went to his garage; we would just play it endlessly here.

And at first I was like, “What is this weird music?” And then the more I started to listen to it, it was the attitudes. There was irony and there was sarcasm and there was a kind of bitchiness that in the world of developing masculinity or whatever that we were exposed to on a day-to-day basis, just was not allowed. To hear Morrissey embracing it in this kind of like Oscar Wilde sort of fashion, we were just like, “Ooh, that’s cool.” [Laughs.] We just liked it.

And the clothes and the attitudes. We were these two white trash kids in the Oregon rain, walking two miles to the mall, to hang out on a Saturday because we’re broke and have nothing else to do. You listen to the Smiths, and it was here’s this faraway world — and the Cure too — there’s this world of metaphor, this world of irony. And they’ve got crazy hair or a cool pompadour and all these guitars.

Something about it all was like discovering a lost civilization, because we weren’t exposed to this anywhere else. And it was like an entry point. It’s like you open this door and you go through this door and then on the other side of this door is the rest of the world of ideas or the world of art.

Writing the book and going through all this, how did it influence the music on the record “Hollywood Park”? How did you find yourself changing as a musician or evolving — or did you in any way?

In some ways, the record was a return to the type of songwriting that I’d done at the start of my career. I guess I was less concerned with structure, less concerned with trying to write songs I thought might be popular. Instead I went back to try to tell a story as I understood it — and thinking about, you know, what I think about when I listen to songs, which is the effect it’s having, what I am trying to get across.

I tend to write about whatever I’m going through or thinking about a lot in that moment. And in the last five years, I was processing my father’s death; I was processing all this stuff of when I was a kid, because that’s what I was writing about; and stuff before my father’s death.

We were really going for a soundtrack. A movie can have a soundtrack; why can’t a book have a soundtrack?

That makes sense, because there is sort of a cinematic or dramatic arc not only to the kind of the sequencing of the album, but also the individual songs. There is space to it that I definitely picked up on that.

That’s what we’re trying to do. I was thinking about Pink Floyd, “”The Wall” a lot. Not trying to sound like Pink Floyd — but the old saying is, you don’t do what they did, you seek what they thought. And in the case of Roger Waters, he’s dealing with childhood trauma because his father was killed in World War II.

And so you see the historical events around that — you learn a thing or two about [the war]; it’s very much alive in the record. And then you learn about his trauma as a kid, and then you learn about how he’s trying to process it as an adult and his artistic relationship to the world, his inner monologue and then his relationships.

That was the idea in the case of “Hollywood Park.” It was like, “What are these historical forces?” There’s my dad’s time in prison; there’s heroin addiction; and my uncle’s in Vietnam and then them joining the cult and us escaping from the cult. And these are all trauma incidents and historical events that led to the trauma, and eventually [there’s] me trying to deal with them in adult relationships in the middle third of the record, and all the different ways that plays out in my entire inner monologue.

And then by the end, [I’m] coming to some new conclusions about family and having lost my father and trying to remain in dialogue with him and realizing just how fierce that love was —and how much I really want to encourage it in my own life and hold on to it.

“Hollywood Park,” both the album and memoir are available now.