WeWork, co-founded by Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey, was designed to provide flexible shared office space for startups, freelancers, and others entrepreneurs. Neumann, who was the public face of the company, insisted "We" — and the emphasis was always plural — "want to make the world a better place — and make money doing it." He gave employees stock options, suggesting they had equity in the company.

For many of the employees and clients of WeWork, Neumann was charismatic and brilliant, and he sold them, not unlike a cult leader, on the benefits of collective energy and having a purpose in their work. He also helped create WeLive, which took the office environment home, creating a "co-living" space, which looked not unlike a college dormitory, and "WeGrow," a private school, spearheaded by Neumann's wife Rebekah, a cousin of Gwyneth Paltrow.

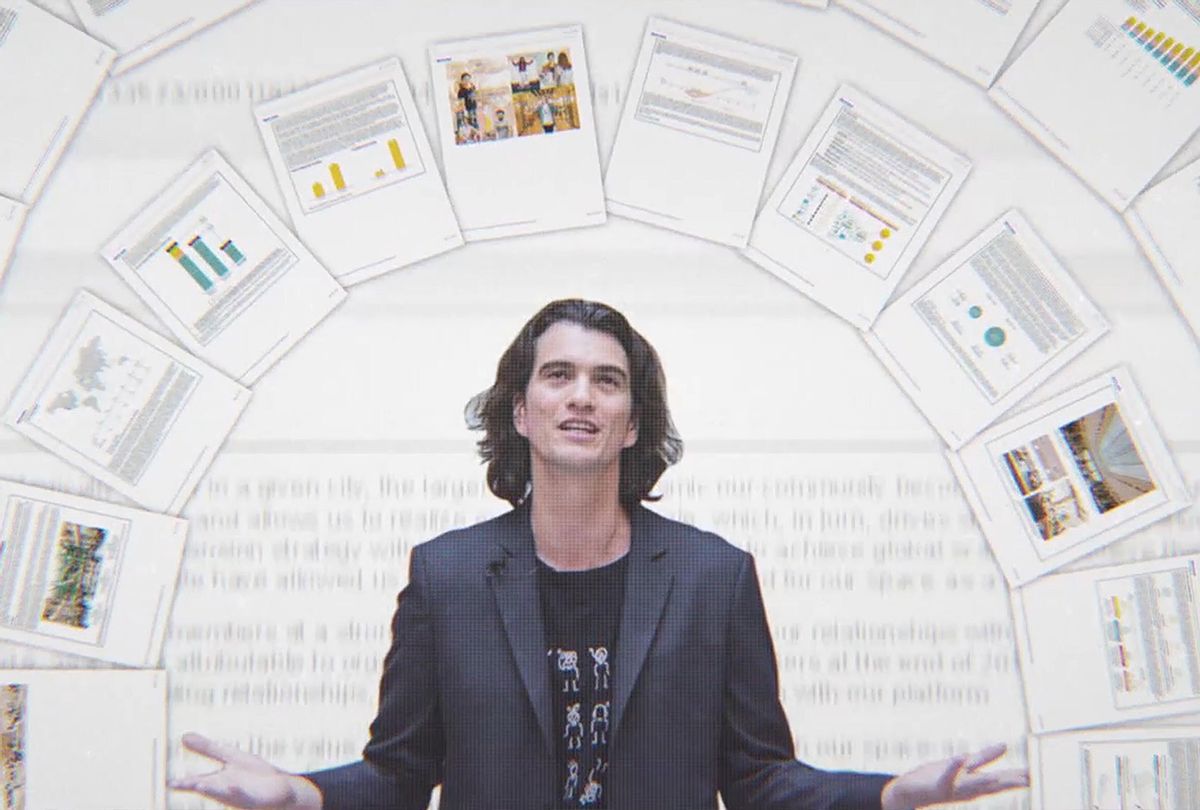

"WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn" is filmmaker Jed Rothstein's ("The China Hustle") shrewd portrait of Neumann, a man whose ambitions, hubris, and greed exceeded his capital and reality. The documentary shows how Neumann become the largest lessee in New York City, but denied that WeWork was a real estate company. He spent money as fast as he could borrow it, getting a $4 billion injection from Softbank's Masayoshi Son when needed. Unfortunately, Neumann postponed his IPO, and questions about WeWork sent the business into a bankruptcy in a matter of weeks.

The overvalued company was flailing behind its positive messages. After the IPO failed to launch, Neumann stepped down from WeWork — but don't feel bad, he failed upward and got a $1.7 billion payout. Most employees who left WeWork got low self-esteem issues, and a begrudging feeling of schadenfreude.

Salon spoke with Rothstein about his compelling new Hulu doc.

What appealed to you about Adam Neumann. And by that, I mean, how would you have been seduced by him as so many others were?

He was charismatic and presented a vision of change and purpose. It wasn't just come sit at a desk and process deals. It was that you are going to be part of something that was going to change the world and make the world a better place. That's a very compelling pitch. I'm sure if I had come across it at the right time, it would have been pretty compelling, to me too.

Your film is a cautionary tale of hubris, ambition, and greed, and I love that your documentary exposes this hypocrisy of how "We" became "I."

When Adam sees this, if he hasn't seen it already, I hope he would like it. To me, the story is of a guy who has a big vision, and gets a lot of people to follow it, and then kind of loses his way. He gets greedy and makes some very selfish choices in the end. And there might be people who hate him for that — and maybe justifiably so. But I don't think it is a story of a bad, evil person, or a one-dimensional character out to scam people. I think it's more nuanced and complicated than that. I hope that if he sees it, he would feel that.

Do you think Neumann could have done something right to make WeWork work?

Yes, I do. At the end of what became his journey with WeWork, there were all of these red flags in the S1 [SEC form] that were not illegal, but perceived as self-dealing or bad corporate governance: having the company buy the trademark from you for $6 million; having office locations you own be leased back to company; having the leadership succession plan so his wife would choose his successor. There are things that when a company goes public, institutional investors would look at and see these red flags and they might expect a young company have some of these. But WeWork had all of the bad red flags. There were people inside the upper echelons of WeWork who probably encouraged him to unwind some of those before he went public, and if he had been a little more temperate, the media would not have had such a feeding frenzy on their efforts to go public. When things did unwind, he had put himself in a position to have the leverage over Softbank to extract an enormous amount of money. More consideration could have been "we" as to the "me" when things washed up on the rocks from their first efforts to go public.

A credit indicates that Adam and Rebekah declined participation. How actively did you chase them?

Very. We spoke with their rep extensively and urgently, and over a good period of time. At a certain point I thought it was possible they might, but they didn't.

What about Miguel McKelvey? He seems conspicuously absent from the narrative. What is his story?

Miguel was important in forming the idea of what WeWork became and especially important in envisioning the physical spaces, bringing light in the space, making them much more pleasant offices to be in than a lot of the earlier version of coworking spaces. We focus more on Adam because he was the public face of the company, though Miguel did appear. Adam was much more involved in the elements of the story that drove WeWork up to its delirious heights and brought it down so quickly. Those meetings and relationships really hinged on Adam, so he became a more central focus to the story. From speaking to people who were at WeWork, Miguel's title near the end was Chief Community Officer. He was keeper of the flame of the original idea. Interestingly, he stayed at WeWork until June of 2020. He did not leave when Adam left.

This is very much a "follow the money" story, only in some cases, there was no money to follow. Can you talk about how you pieced the narrative together?

Every story like WeWork's has multiple threads and multiple narratives. It was important for us to understand what was the special sauce — why did this thing come together? This wasn't a Madoff thing where he just made stuff up. There were office spaces; people did rent them. In the garden years, they were growing fast, and did these things that created an esprit de corps. But what were the inflection points where things changed? Perhaps the biggest one is when Masayoshi Son invests $4 billion and says, "Go crazy." That changes the nature of the business. They have enormous cash to play with, but also enormous expectations put upon them. It opens up pressures to grow and achieve certain financial benchmarks, and that's where you begin to see cracks in the fantasy tale. How do you tell that part of the story? What are the pieces of evidence that show that is happening? We found stories from people like Justin Zhen and Johanna Strange. Johanna was an employee and Justin was a member, but they began to see that the story being told was not what was really going on. But it's a big complicated story. Maybe that's not the whole thing, but it leads us in a direction to look at other elements of what became an increasingly divergent path between what they were preaching and what was really going on. That split between the "me" and the "we" encapsulated in Adam in his personal story and reflected in the company itself. That's why I like financial stories. When all this money is on the line, it clarifies things. It's a story about how people behave. Money makes the decision points happen and injects the drama.

Yes, your film, "The China Hustle" did that.

The impetus behind that film informed this one. The guys in "The China Hustle" started making so much money that they asked questions about why they were able to make so much money. They asked, "How is this company so much more profitable than every other company of this type?" When they couldn't get answers, that's when they dug into it more, they determined they were shams and they began to short them. With WeWork, you had a huge chunk of New York Real Estate firmament and a huge chunk of the savvy investors in Wall Street and Silicon Valley, and smart reporters enamored of WeWork and Adam. There were lots of reason to get on the train, because it seemed like a great path to be on. But a few people started saying, "Is this a tech company? How is it a tech company? Aren't you just renting real estate and slicing it up into smaller pieces of real estate?" When they asked these basic questions, the answers got more filled with yoga-babble and talk about community, and different standards of calculating money. Not asking those simple questions, [explains] why something can spin up so big and collapse as rapidly as it did. They didn't have answers to some of those questions.

So what lessons are learned here?

In a way, the system worked. Sometimes you make a film like "China Hustle" and the moral is we have to change the system. This story is why do we keep encouraging these super-heroic founders to emerge and save us? Adam is going to reimagine work and living and school. And it's going to be worth $47 billion even though no one can quite figure out how the rental math works that way. We want these heroes to save us from ourselves. But it's not bad to encourage visionaries, but we need to have a system that encourages them to walk the walk a little more. With WeWork, we can say the financial system at some level, worked. The S1 process required this revelation of the numbers. It didn't add up, and investors who were not excited by the communal "we," and solving problems beyond the world of office space, were interested in, "Is this a good investment or not?" It didn't add up. That saved the losses from being socialized to the broader market. I would argue the staff members and people who worked there in expectations of these payoffs, suffered and emotionally, people who bought into something that turned out not to be what they were sold by Adam.

How did you assemble the film and footage and select the interviewees to help tell the story?

I knew WeWork had filmed a lot of its own story and put it up on social media sites and its members did too. I wanted to tell the broader experience of all the participants in the WeWork phenomenon. It was a blessing to stitch together this quilt. It gives us a great scope. You can see how the physical plant of WeWork grew and changed, and you see how Adam and others involved grew and changed. I was happy to tell the story through all of this footage.

I was especially fascinated by testimonies of folks like August Urbish who bought into the WeLive idea. What observations do you have about him and his experience?

August was very moving. The WeLive story was important for me to include. I didn't know much about it before I got involved in the film. It was a new and interesting dynamic, and it was the most thoroughgoing manifestation of the WeWork idea. You are living the "We" life. August was working in a WeWork, and living in a WeLive. His whole life was in this community, and that seemed like a totalizing expression of all the ideas that Adam and Rebekah and Miguel were putting forward. What's it really like when someone goes all in as August did? His experience is the most delicate and subtle form of heartbreak. When he talks about realizing one day that it's weird to go out to other places because no one wants to leave the building, and his other friends from before visit only once because it's too weird. Those are cult-like characteristic. I don't want to say it's a cult. There's a psychological element to being in the group and forming an exclusion of people and things not in the group. August realized that there was a cost to that, and he didn't want to pay it anymore. What could the WeWorld have become if it had gone into full flower? To me it is like a stress test that puts the ideas behind it into a harsher light. They work as business slogans, but when you are really trying to build a complete community of people living inside this philosophy, what holds up and what doesn't?

You made this film during COVID. What are your thoughts about the impact of the pandemic on places like WeWork?

I would bet that WeWork and other companies like WeWork will be very well positioned when we come out of COVID. I don't buy that everyone wants to work at home forever. There are things about having a work community and workspace — especially if you have kids and don't have a big house, or it's hard to focus and concentrate. People will want to return to offices, but the way we work, and the rigor of 9-5, will be transformed. I imagine we will have more coworking spaces, whether you are a small company or an enterprise company. Big companies will be happy to shed be rid of long leases. They can be networked and have space-flexible leases. [WeWork] was prescient about the need for more flexibility in the workspace and they will strangely be fortunate in ways they couldn't have anticipated when we come out of the pandemic. I think ultimately, we will all be happier for it. We want to work together and see people, and have this community, and not have it be structed the same way it always was. Even if you live alone, psychologically, it is nice to have a separation. If Adam had been smarter about it, he could have held on through this. I'm sure he'll have a second act somewhere.

"WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn" premieres Friday, April 2 on Hulu.

Shares