As a Black man coming of age in the era of mass incarceration, I know how easy it is to go to prison. Especially in my hometown of Baltimore, when Martin O'Malley was mayor, and all you had to do to earn a few nights at central Booking was be Black and walk down the street. The arrest was so bad, and so racist, that the former mayor turned governor was sued by the NAACP and ACLU.

And we always hear about the scores of Black men and women coming in and out of the system –– and how poor politicians push poor policy on top of poor policing, and how the sum of all continues to fuel mass incarceration, but what about the families of the incarcerated men and women? If you are the provider, and you go to jail –– how does your family survive? If you are released, and become unemployable because of your record, how do you resume your role as a provider? And if you can't resume the role of provider, then what's to stop you from committing another crime and repeating the cycle over and over again, leaving your family in the same position? Award-Winning director Garrett Bradley captures this cycle, and the other side of mass incarceration brilliantly in her Academy Award-nominated film "Time."

Amazon's "Time," directed and produced by Bradley, follows the journey of Sibil "Fox" Richardson, a true warrior for justice as she fights for her husband's freedom while challenging our broken system, making a living and raising their six boys. I recently got a chance to talk with Bradley on an episode of "Salon Talks," about how she got involved with the project and the role of artist in our nations fight for equality.

You can watch my "Salon Talks" episode with Bradley here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below to hear more about the mission behind her creativity, the success of "Time," and the power of enjoying the moment over always focusing on what's next.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

How have you been surviving the pandemic and all this craziness that's going on in the world?

Surviving the pandemic, I don't know. I think you just take it day by day. I think that the pandemic has been illuminating for all of us, right? It's just been a unearthing of everything that's always been there, so I'm grateful for that, actually, and in a place of just thinking about how we can change the world, really. That's how I'm spending a lot of my time.

It seems like as a filmmaker coming out with a project around this time, you do have a lot of people in the same place at the same time, so a lot of people are going to get a chance to see and enjoy the film. I think it was amazing. Can you give our viewers just a brief background of the project without giving too much away?

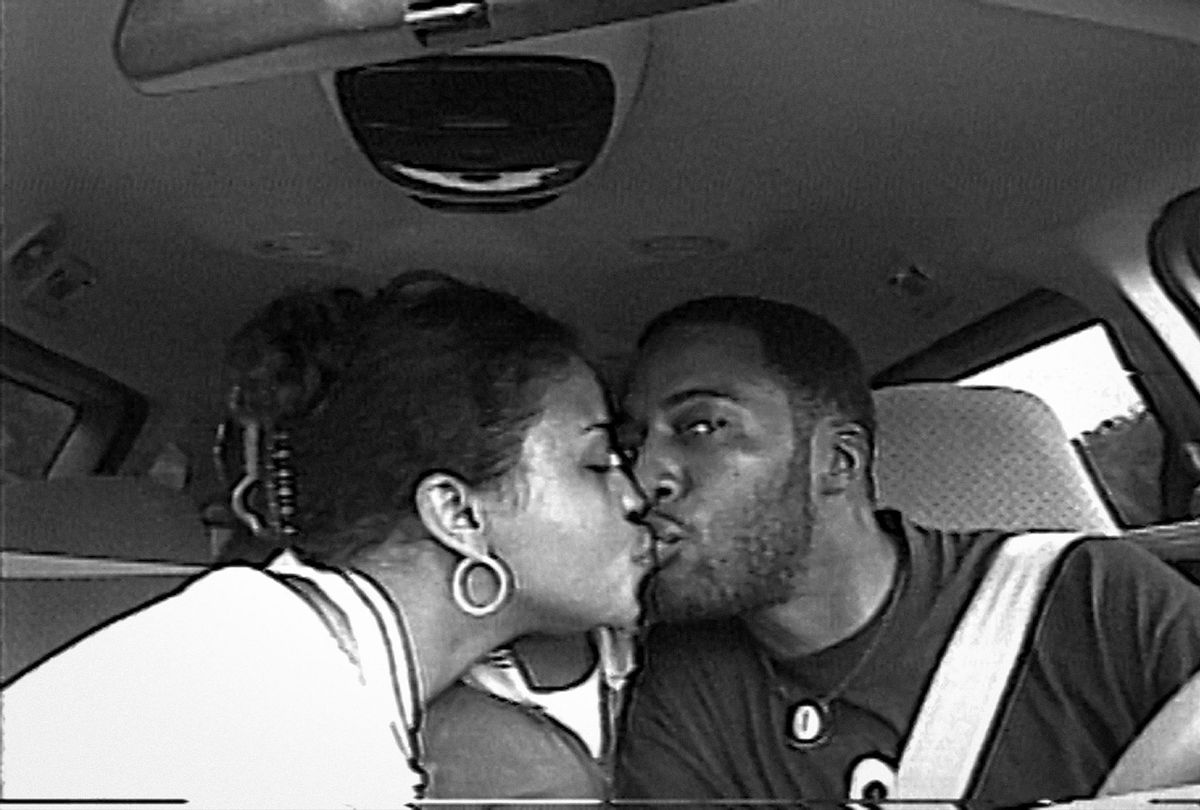

Yeah. It's so funny. It's like that's always the hardest thing to do, actually, is to recap, but I'm going to do my best. At the heart and soul of it, really, without even getting into the minutia, "Time" is, it's a love story, really, that spans over two decades and it's really centered around Fox Rich as the family matriarch who spent 21 years fighting every day to reunite her family and we're in New Orleans, Louisiana. I would say that's the meat and potatoes of it. I'd like to think that all films and all things that we make, there's also so many more layers and nuances within that.

How did you get involved in the project?

I feel really, really lucky that every project I've made has just come out of my natural and real relationships with people and things that are happening in my community. I've never gone out thinking, "I want to make a film about incarceration." That's something that has just been in close proximity to me and came out of making a short film called "Alone," which I always say for anybody who's out there watching this. I didn't know anybody at the New York Times. "Alone" was a New York Times Op-Docs film. I went to their website, I submitted an idea. They responded to me three months later and I made the short film, and so anyone can do that, first of all. That film was really, it was also centered around a woman who was navigating the system, trying to figure out how to really put one foot in front of the other while her partner awaited trial for a year and a half in a private prison in Louisiana.

Because of the stigma around the incarceration, there were very few people that she could talk to, to get support, to get information. So the impetus for that film was really trying to facilitate intergenerational conversations between women who could offer support to one another. I contacted this organization, did another Google search, contacted this organization called FFLIC, Friends and Families of Louisiana's Incarcerated Children and Gina Womack, who's the co-founder and director of that organization picked up and said, "The first person that Lon needs to speak with is Fox Rich." So Fox is briefly in "Alone" and makes a really vivid connection between slavery and the prison industrial complex. Again, it wasn't like saying, "I want to make another film about incarceration," but, to me, it felt like there is such an absence, such a void of talking about this issue from a Black woman's point of view, from a mother's point of view, from a family's point of view and it just was a natural thing that happened.

Something that just blew my mind was how Fox has so many home videos in a time where everybody wasn't walking around with their cell phones all day. Could you talk about that a little bit and what was she shooting on?

A Hi8 mini or mini DV tape camcorder. So there's a couple of things to say about it because I think that the Black family archive in America, for us I feel like is, it's a type of resistance in and of itself, because it's evidence of ourselves as we see ourselves in a way that works in parallel to mainstream media where we don't always see ourselves as we see ourselves, right? We are building our own legacy in the process of documenting our families. I think that for Fox, and that even is a added layer when you think about it in a Southern context, in a context in New Orleans, in Louisiana, where Katrina obliterated the legacy of many, many families, right?

So there's that. I think that there's also this element of what you're speaking to where Fox is literally speaking to the camera. This is before social media. This is before it's actually going out anywhere. I think it was a type of therapy for her. I think it was, on some level, her also finding her voice and transitioning from, we see this evolution of Sibil to Fox. But it was also in my mind, this really incredible testament to her character, to her complete lack of doubt that her husband would come home and see these videos. I think that that's a really incredible thing not to overlook because self-doubt is something that sometimes in our worst moments, we are led by.

This woman had no doubt in her mind that she was going to create this archive and document these moments and also in doing so, recreate imagery and symbolism around what being wholesome was and what being an American family was. It was incredible.

So in looking at all those home videos, did that have something to do with your decision to make the film black and white? Where did that come from or how did you arrive on that, because I'm pretty sure her videos were in color?

They were in color. Yeah. The videos were – they were beautiful and they were so vivid and so lush – and the black and white, again, I thought I was making another short film, to be honest with you, because "Alone" was 13 minutes long. So I was really committed to all of the stylistic and visual choices that I made with that short film. I really wanted those to be adapted into this other film, so I didn't even have to think about it. I knew it was going to be a black and white. I knew I was going to shoot it the same way. When I realized that the archive existed at the end of filming, not something I had the forethought to be able to include in my mind. That was something I learned on our last day of shooting. It was more like I knew that self-documentation was a part of her life, but I had no idea that she had 100 hours of personal hallmark. She, herself, didn't know that she had 100 hours.

I just feel like single mothers who have to raise kids while the fathers aren't present are just too often left out of the conversation. I think you did a great job amplifying that. Fox's voice is extremely strong, and it deserves to be heard. What should the world know about women who face this in this country?

Well, that's a great question. I think, first of all, Fox herself I think would pay homage to her mother, to Miss Peggy, who was also a key role in keeping the family together and taking care of the boys. I would also say that although Robert, their father, was physically separate from them, was incarcerated, Fox and Rob made a commitment to one another when they both were incarcerated that they would not let the system separate them. That unity is a part of resistance, right? We've been separated systematically as Black and brown people from the beginning of time, from the beginning of the New World. So being together, whether incarceration is a factor or not, is a type of resistance to that history and as parents, they were keenly aware of that.

So I just am wanting to say Fox did an incredible job raising her six sons, but I think she, herself, would also want to say it came through the support that is intergenerational, that was from her mother and that was also very much connected to her husband and their father staying involved in their life. I think if there's one thing that is actually really important that I would hope people take away from this film really is this idea of forgiveness, because the film is not trying to make a case for innocence. They committed a crime. They made a mistake. Fox is very clear in saying they were in a desperate situation, and desperate people do desperate things, right?

But what does it mean for us, then, once the crime has been committed, where do we go from there? How do we actually think about forgiveness as a key part of changing this world, as a key part of giving people an opportunity to contribute to society and to contribute to their families in meaningful ways? What do we actually gain from separating people and throwing them in a cell and keeping them there for a lifetime? What's actually lost in that? I think whether someone is touched by incarceration or not, I think it's about having an imagination saying, "Imagine if I were in that situation and what is it that I need to forgive in myself, what is it that I need to forgive in others?" If we can think about that as the bedrock and the foundation of society, we can actually start to create change.

Something that I don't want people to miss in the film, is just this whole idea of plea deals and how important they are to our criminal justice system that it just totally doesn't work. Could you speak to that?

Yeah. I think that I made a choice, actually, when I was making the film, not to get into the intricacies of the legal system because I feel that to a certain extent, "Time" really stands on the shoulders of a film like "13th," right? Ava [DuVernay]'s film "13th."

Her film does an incredible job of really mapping out, unequivocally, for people, the connection between American slavery and the prison industrial complex. She does that through the minutia of the system, understanding plea deals, understanding bad lawyers, understanding wanting people to be punished from the beginning without any kind of fair trial, without any real guidance in any kind of real way. What needs to exist parallel to that is the human experience and is the effects of the data, the effects of those facts. I'm going around that question a little bit intentionally because I'm trying to make a point that in order for us to actually demand change and understand change, we need to separate ourselves from our political allegiances, from our political identities and think about, "Who am I outside of what I think I know about a system?"

So I can try to explain a legal system to you till the cows go home, but I'm asking you to actually ask yourself, "Who are you as a father? Who are you as a mother, as a daughter, as a grandparent?" If something was done that was wrong, is locking somebody up for a numerical life sentence really worth it? What's actually lost in that? What would be gained again through this idea of forgiveness and how do we shed light on the hope and the resilience and the strength of 2.3 million American families, right?

That's really where I want to center the conversation because I think that there are conversations that are happening around the legal system that are critical, that need to continue to be illuminated. But in parallel to that, we need to also talk about the human experience and the human effects of that on love, on Black love, on Black joy too.

Do you feel like a lot of your work or the bulk of your work is mission-based?

Yeah, absolutely. I think anything you put into the world is mission-based. I think it's impossible to do anything, even our conversation, even "Salon Talks" is mission-based on something because it's like you have an intention, and then, you're giving something to the world. I think that that's even more critical when you understand the medium of filmmaking, which is around images, and images are so powerful. They last longer than us. They, oftentimes, are seen sometimes without context, right? The image itself is both specific and it offers context all at the same time.

So how we see ourselves, how we document each other says a lot and I think everything I do is motivated by the idea of celebrating people, celebrating families, celebrating individuals in their strengths, in their beauty, in their resilience. I don't work with people that I don't love, that I don't have respect for, and it's really about trying to share that with people. I wouldn't even say it's like giving voice. I think it's saying, "There are these voices that are already there with or without me, and I would like to help amplify that. I would like to help celebrate that."

Do you feel like some of these things are going to cause a shift in and lead towards systemic change?

I hope so. I think all we have is hope. We have to aspire to something greater in order to move forward. I think that images, again, when you think about the Vietnam War and that being the first time that people could see war and being able to see it meant that they could believe something and then be angry about something and protest something. When we think about Emmett Till's mother and her brilliance and understanding what it means to have an open casket so the world could see. Images hold systems accountable in a way that sometimes nothing else does. So I feel like part of my mission, going back to your question, is in creating images that prove what's happening in our country and the system, the prison industrial complex is invisible by design.

The only evidence, sometimes, of 2.3 million people being incarcerated is in the family, is in those that are serving time on the outside. So I think that there is a call to action that is also about demanding more sight, demanding more visibility and transparency around what's happening. Angola, which is a private prison where Robert was incarcerated for 21 years, with several plantations that were consolidated into one plantation that is 18,000 acres of land. My drone could only get a fraction of that and so that says something to us about why people are not on the streets demanding that this be taken down and stopped right away. I don't think it's because people don't care. I think it's because they literally don't know and that, again, is by design. That's intentional.

What are you working on next?

Well, to be honest with you, I really am trying to just honor this moment right now. It's always natural for us to try to jump to the next thing and I'm trying, right now, just to enjoy this with the family, enjoy this with our film team and just have a good time and then sleep a little bit and then figure it out.

"Time" is available to stream on Amazon.

Shares