Dr. Thomas Price, a senior lecturer of evolution, ecology and behavior at the University of Liverpool, has had a lot of time to consider how humans are at a disadvantage because of our external reproductive organs. Some animals have testicles inside their bodies, but others need the testicles outside of their bodies so they’ll be cool enough to produce sperm in a process known as spermatogenesis.

This has a well-known downside, though. As Price did research on testicles and fertility, he learned about that downside firsthand.

“Five years ago, back when we could all meet up, we used to play 5-a-side football at work,” Price told Salon by email. “I did a (I like to think) Van Dijk–like defensive tackle on one of the PhD students who was about to shoot. Unfortunately he followed through and booted me in the plums.”

He recalled, “As I lay there, it really brought home to me what a terrible, terrible idea it is to have external testicles. Elephants, dolphins, and hedgehogs all have internal testicles. I really think it would be a lot better if we did too.”

The risk of excruciating, embarrassing and arguably comical blunt force injury is not the only downside of having your testicles outside your body. This fact has been demonstrated by the work that was being done by Price and a team of ecologists. Price was the senior author on the study subsequently published in the journal Nature Climate Change, which proposed that climate change could cause extinctions among species with external testicles.

It is not hard to ascertain why. If species need their testicles to be kept at a certain temperature so they can reproduce, there is a risk that they will become less fertile as the planet’s average temperature rises. Unfortunately human beings since the Industrial Revolution have been emitting so-called “greenhouse gasses” like methane, carbon dioxide, water vapor and others, that trap heat on our planet. This is expected to cause apocalyptic conditions over the next few decades: extreme weather events like hurricanes, blizzards and droughts; refugee crises as coastal cities are flooded and marginalized populations disproportionately suffer; and resource scarcity as it becomes harder to grow food and maintain commercial supply chains.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Now Price and his colleagues have added boiling testicles to the list of climate change-related problems. They studied 43 species of fruit flies (Drosophila) and found that their distribution across the globe more closely correlated to the temperatures at which males were sterilized than the temperatures at which the flies died.

This suggests that, when it comes to predicting the futures of a number species (including humans) in a post-climate changed world, fertility may matter more than is widely appreciated.

“I think people just hadn’t made the connection,” Price told Salon. “It is a bit surprising, because people have known for at least a century that spermatogenesis requires low temperatures, which is why testes are kept in a sack outside the body while ovaries and most other important organs are protected deep in the main body cavity.” He added that it is also more difficult in general to measure how temperature impacts fertility as opposed to how it can kill organisms.

“There is no visible sign that an organism has become infertile — you have to heat them at a specific temperature then give them opportunities to mate,” Price explained, mentioning that his co-authors Steven R. Parratt, Benjamin S. Walsh and Nicola White “spent an enormous amount of time doing the practical work for this study.” By the time they were doing their research, Price noted that a number of scientific groups had begun to simultaneously realize that climate change could impact fertility.

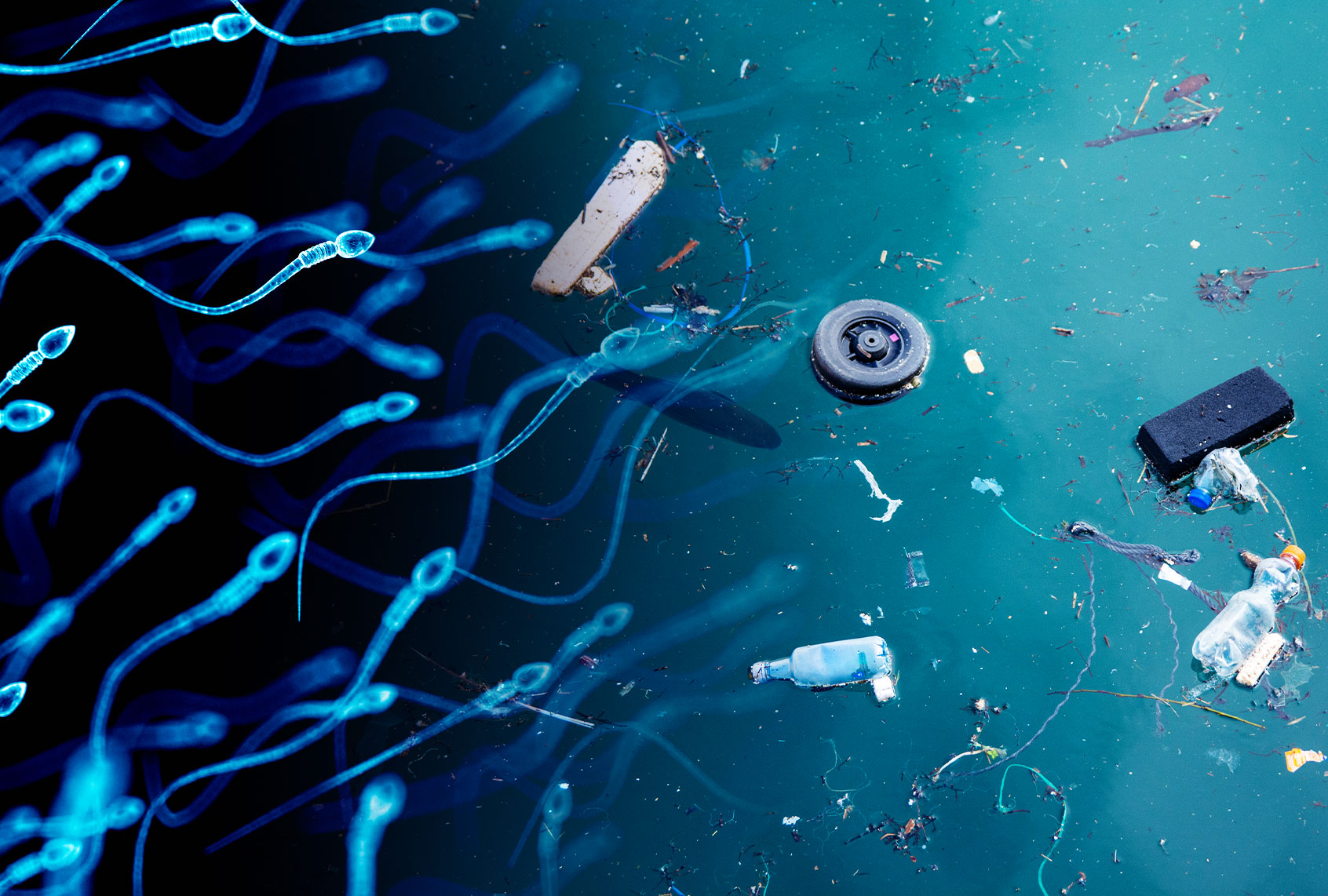

Salon asked Price whether he felt his research intersects with research indicating that chemicals in plastic are also making humans infertile, including by lowering sperm counts, as well as with a recent World Wildlife Fund report which found that population sizes of “mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish” have fallen by 68 percent since 1970. He said that scientists do not have data on how plastic pollution might combine with climate change to further reduce male fertility, although he guessed that “individuals whose fertility is already damaged by pollution, including plastics, will be even more vulnerable to temperature stress during a heatwave.” When it comes to mass extinctions, Price expressed the personal view that there are many other factors driving them including habitat destruction, the introduction of invasive species, disease, overhunting and other effects of climate change.

This is not the first recent study to link climate change to fertility issues. Scholars from the University of Queensland published an article in the scientific journal Environmental Research arguing that there may be a connection between temperature rises and stillbirths.

“Climate change can have a multitude of impacts on an individual’s health, especially among vulnerable populations,” the research team behind the study told Salon by email at the time. “For pregnant mothers, extreme weather events can impact access to antenatal services and increase risk of heat-related illnesses. Mothers living in low-resource settings are particularly vulnerable to these effects.”