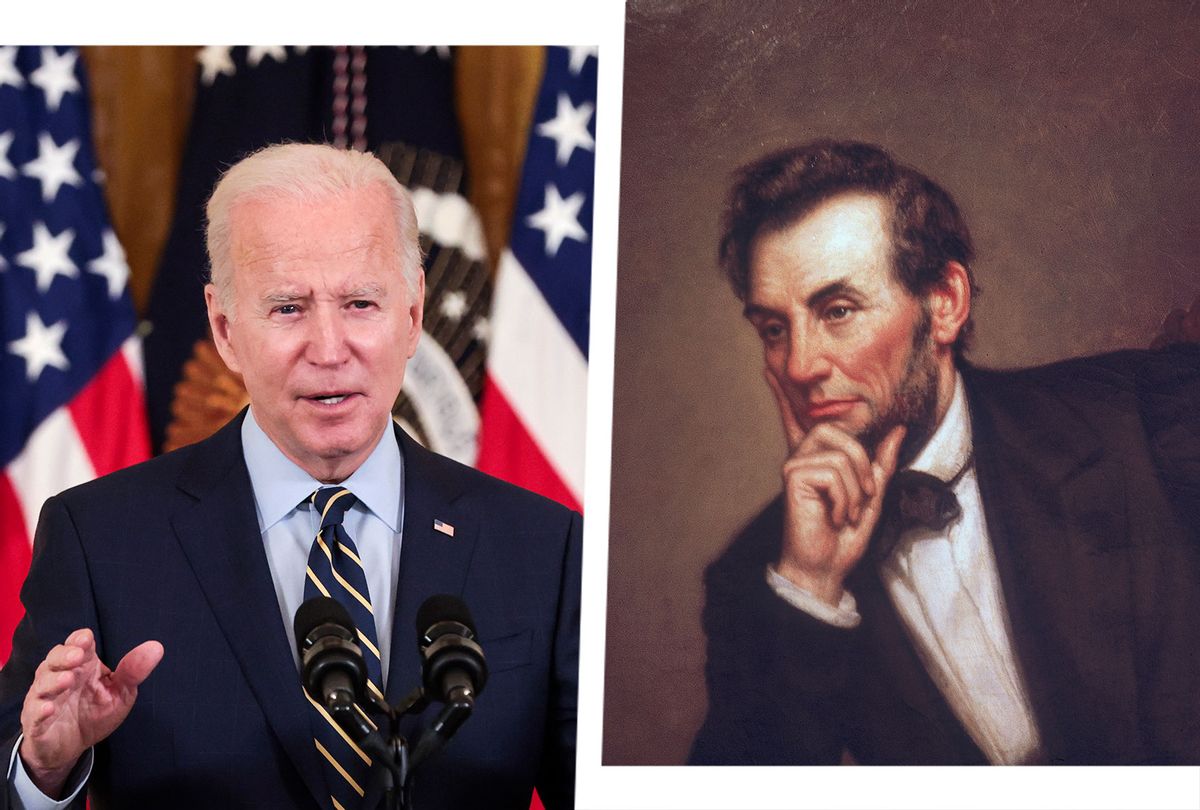

Only one president, before the current one, won a national election only to see a large proportion of the country outright refuse to participate in our democracy rather than accept the result. That president was, of course, Abraham Lincoln. He concluded that those who conspired in an illegal plan to undo the American experiment in democracy had to be permanently banished from politics. It is a lesson Lincoln's successors forgot, and arguably one that should be studied carefully today.

There are key differences, to be sure, between the situation faced by Lincoln and what confronts Joe Biden today. Lincoln's victory in the 1860 election was controversial because of his opposition to slavery. No one claimed the election result itself was fraudulent — a region of the country simply despised him for being a Republican, with Lincoln's name being left off the ballot on the ballot in most Southern states. What's more, the aftermath of Lincoln's victory led to a literal civil war, and despite some dire predictions we are not close to that in the 21st century. In addition, while the 1860 election tore America apart because of one grave and highly divisive issue (that being slavery), the 2020 election posed a major threat to democracy largely because of the damaged ego of a highly narcissistic candidate.

In both cases, however, we see a large, reactionary faction rejecting an election loss, and that act serving as the catalyst for a crisis of democratic legitimacy. Lincoln faced a violent rebellion that literally caused armed conflict, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths. What Biden faces today is more difficult to define, but looks to be an effort to subvert the rules of democracy in practice while maintaining rhetorical support for them, and while nominally abiding by existing laws and working through existing institutions.

The political question made visible in both cases is one of self-preservation rather than principle. To what degree can a democracy tolerate the actions of those who wish to destroy it? How much defiance and resistance is permissible before democratic institutions lose all meaningful authority?

RELATED: The Revolution of 2020: How Trump's Big Lie reshaped history after 220 years

We can never know how Lincoln would have governed during Reconstruction, since he was assassinated shortly after the Confederacy surrendered. But in waging war against the seceding states in 1861, Lincoln acted decisively to save democracy, something his immediate predecessor James Buchanan was clearly unwilling to do. Lincoln considered his legitimacy as the democratic leader of the entire nation to be beyond question, and did not hesitate to send men to kill and die for that principle.

Based on the reconciliation policies Lincoln discussed during his lifetime, he clearly had an intended strategy for bringing former Confederates back into the Union. We could call it a carrot-and-stick approach: Go relatively easy on most defeated rebels, below the highest ranking political and military leaders, and make it relatively easy for Southern states to begin governing themselves again (once they accepted the abolition of slavery). The so-called Radical Republicans disagreed with Lincoln on many details and wanted a much harder line taken against former Confederates in the South, and even Lincoln understood that tolerance and generosity would only go so far.

With Lincoln's approval, Congress addressed this question directly. "The laws enacted by Congress to prevent former Confederate leaders from acquiring power after the Civil War provide an object lesson for our time," Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe wrote Salon by email. They have been enshrined in law as precedent for stopping those who would commit violence against a democratic government. Of the resulting statutes, Tribe identified this one as the "most pertinent":

Whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both; and shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

This principle — that involvement in direct insurrection or rebellion must lead to being exiled from politics — was added to the Constitution itself through Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, one of three amendments passed in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. Every former Confederate state had to ratify these amendments before rejoining the Union.

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any state, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any state legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any state, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Tribe explained the rationale behind the "disqualification provision" this way: "The will to violate one's oath to uphold the Constitution of the Union couldn't be relied on to evaporate just because the rebellion had been put down when the Union Army defeated the Army of the Confederacy. The authors of the 14th Amendment knew better than to trust the treasonous insurrectionists with the power of any public office, state or federal, ever again" — allowing for exceptions by way of a supermajority vote in both houses of Congress.

After Lincoln's death, however, nothing went according to plan. The new president, Andrew Johnson, was a Southerner and an overt white supremacist. He had opposed secession, but in every other way was sympathetic to the Confederacy.

Under Johnson, the government's approach "was pretty lenient in terms of whether to exclude or allow ex-Confederates to return to power" says Harold Holzer, one of the leading authorities on Lincoln. Although former Confederate president Jefferson Davis was barred from running for office, his vice president, Alexander H. Stephens — who had given the infamous Cornerstone Speech in 1861, clearly identifying slavery and white supremacy with the Southern cause — was allowed to serve as a congressman from Georgia in his later years.

Holzer also told Salon by email that Stephens "even got a speaking role at the ceremony at which Congress accepted the gift of a painting of Lincoln's first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation. That's how far sectional reconciliation went, in the absence of real racial reconciliation." This was a mistake, Holzer believes: "In my view, lax rules and laws allowed far too many ex-Confederates to return to state and federal government." The clear result of this was the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the Jim Crow regime, in which formerly enslaved people — supposedly granted the right to vote under the 15th Amendment — were effectively disenfranchised and subjected to a reign of terror that lasted almost another hundred years.

Holzer draws a clear conclusion from this history. "If there is a lesson to be learned," he wrote, "then anyone who participated in, or fomented, the January 6 insurrection should be barred from ever serving in government again — from the top down."

Tribe expressed a similar view, citing "mounting evidence" that Trump and various Republican allies — including members of Congress — conspired to overturn the 2020 election. If Civil War precedents are followed, he said, "All of those who were involved in that plot, and those involved in the rally fueling and 'inciting' that 'insurrection,' ought to be investigated and, if the evidence is as it appears to be, prosecuted." Under the language quoted above from federal law and the 14th Amendment, that would also mean permanent disqualification from public office.

There is no indication, however, that Biden or Attorney General Merrick Garland are likely to heed Tribe's advice in general terms, still less seek to prosecute Donald Trump himself. For many critics, this looks to be a matter of putting PR or optics ahead of principle. It might also be described as ignoring or avoiding an important lesson from American history: Don't allow traitors to get away with it.

More from Matthew Rozsa on the contradictions and hidden corners of U.S. history:

Shares