There are few words as overused as “revolution,” which has many Merriam-Webster definitions and here means “a fundamental change in political organization.” While people who discuss politics are prone to dramatic talk of “revolutions,” few of the American presidential elections described that way really merit the term. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “revolution” of 1932 changed the nature and role of government in American life, and Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 undid at least some of those changes. But neither election literally altered how our democracy functions.

Those disqualifying details do not apply to the most recent election — the first one ever in which a losing president refused to admit defeat. It’s reasonable to describe that as the Revolution of 2020.

There have been two previous elections that could be defined as revolutionary. The more recent was in 1860, which both revealed and reflected a profound rift in the American polity and led directly to the Civil War. Eleven Southern states decided to secede after the Republican victory because they feared Abraham Lincoln’s presidency spelled doom for the economic system based on chattel slavery. This story is relevant to the Donald Trump era, but the earlier revolutionary election is our main topic here — and that one is actually known as the Revolution of 1800. As things turned out, it was the rarest kind of revolution: One with a happy ending.

RELATED: Untwist your knickers, Trump fans: History says the 2020 election was nothing special

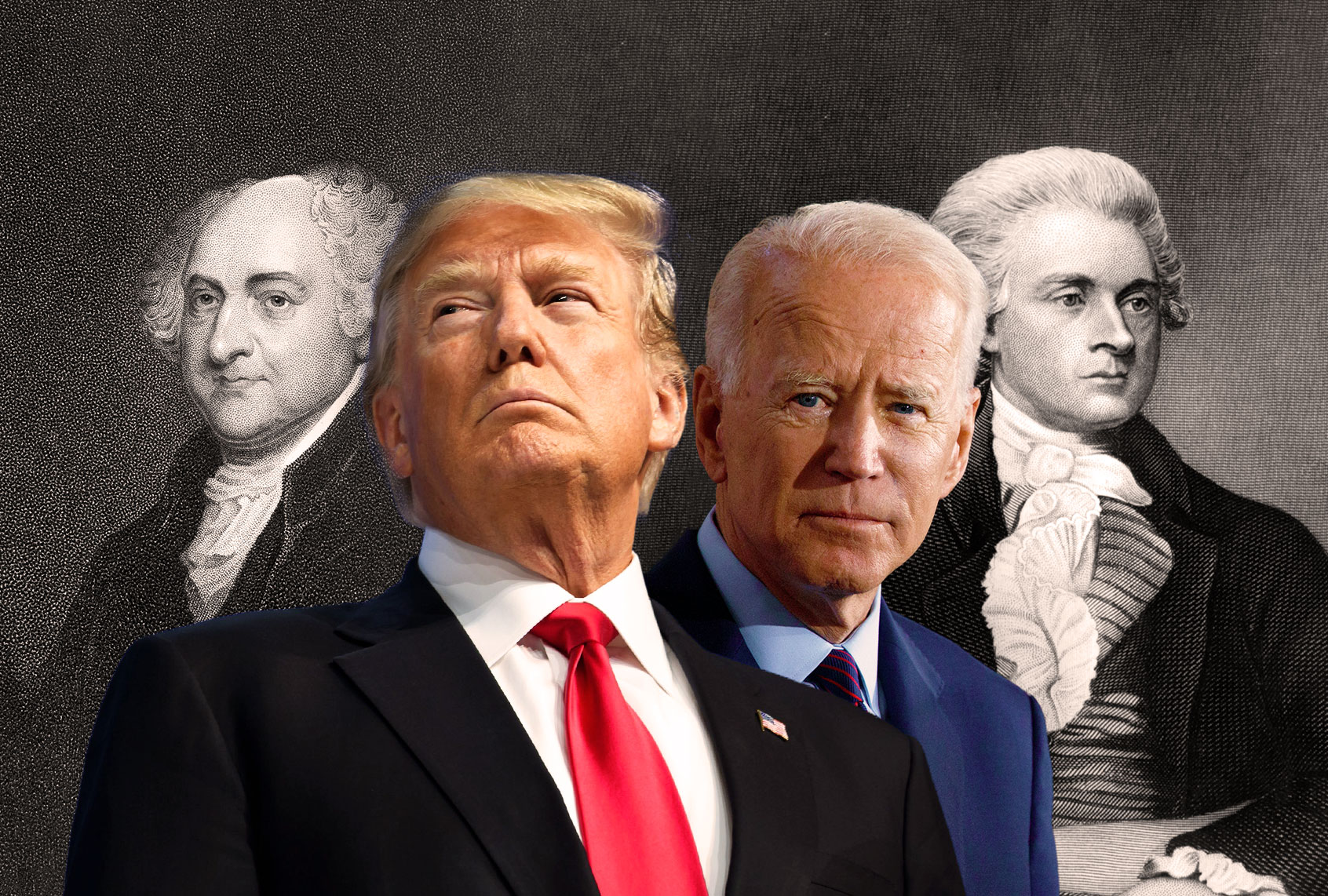

George Washington had served two terms as America’s first president, but without facing meaningful opposition or anything resembling a modern election campaign. After he decided not to seek a third term, the 1796 election became the first to feature serious competition between the nation’s brand new political parties. Federalist candidate John Adams, who had been Washington’s vice president, ultimately prevailed over Thomas Jefferson, former Secretary of State and candidate of the Democratic-Republican Party. But in the momentous election of 1800, Jefferson won the rematch, and Adams — the first incumbent president to be defeated — faced a historic decision: Would he come up with some excuse to cling to power, or simply hand the reins of state to Jefferson and walk away?

If Adams had cried fraud or otherwise claimed the election was illegitimate, he could almost certainly have stayed in office despite electoral defeat. In fact, he wouldn’t really have needed much of an excuse. There was almost no precedent for national leaders voluntarily stepping down in the face of popular rebuke, and plenty of examples — from ancient to modern times — that pulled any aspiring dictator in the opposite direction. But Adams was invested in democracy’s success, and as such swallowed both his pride and his genuine concerns about Jefferson’s political philosophy. He followed the law and surrendered power, and in the process, demonstrated how important the conduct of losing candidates is to democracy. (Like Trump, Adams skipped his successor’s inauguration, but he never tried to delegitimize his erstwhile rival’s presidency.)

Nearly two decades later, it was Jefferson himself who described Adams’ actions as the “Revolution of 1800,” comparing it to the better-known revolution that had begun 24 years earlier:

… that was as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of 76. was in it’s form; not effected indeed by the sword, as that, but by the rational and peaceable instrument of reform, the suffrage of the people. the nation declared it’s will by dismissing functionaries of one principle, and electing those of another, in the two branches, executive and legislative, submitted to their election…

The ideals of self-government captured in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was suggesting, did not become reality until American democracy passed its acid test: The person entrusted with the most powerful office in the land accepted a painful verdict. It had been difficult enough for Washington to leave the presidency, even though he was eager to live out his last years as a civilian. For Adams, it was even worse: He badly wanted to continue as president, and on some level expected to win re-election. In accepting defeat, he proved that democratic government wasn’t just an ideal. It was also workable.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Adams’ precedent was followed without question for the next 220 years, with 10 incumbent presidents leaving office voluntarily after the voters kicked them out. Most were bitterly disappointed by defeat, it’s fair to say, but none of Adams’ spurned successors — from his own son in 1828 to George H.W. Bush in 1992 — tried to concoct conspiracy theories in order to claim they hadn’t really lost. Then came the Revolution of 2020, when the guy who became famous for telling people “You’re fired!” on a reality show refused to accept being canned. That catalyst broke the precedent set in the Revolution of 1800 by America’s first fired president.

Students of history like me, who spent a lifetime before the 2020 election immersed in the story of American politics, instantly recognized the magnitude of what Trump was doing — and understood that he represented a tendency George Washington himself had warned the young nation about. Washington directly identified the fundamental ingredients that made Trump’s coup attempt, starting with a political party so fanatically determined to win that its motivated reasoning could overpower common sense and basic decency. Once the Republicans filled that role, they just needed a demagogue who was sufficiently unscrupulous to exploit that. (Politics is full of egotists, so it says something that Trump was the first politician narcissistic enough to qualify.)

After pointing out that “the very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government,” Washington expresses concern that divisive political sentiments — particularly party zealotry — were “destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency.” In elaborating on this, Washington almost seemed to be looking into the future with a crystal ball. He could hardly have described the hyper-partisanship of our time more precisely if he had actually known about Donald Trump, with all his odious followers and ludicrous assertions. Political parties, Washington writes,

… serve to organize faction, to give it an artificial and extraordinary force; to put, in the place of the delegated will of the nation the will of a party, often a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community; and, according to the alternate triumphs of different parties, to make the public administration the mirror of the ill-concerted and incongruous projects of faction, rather than the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common counsels and modified by mutual interests.

However combinations or associations of the above description may now and then answer popular ends, they are likely, in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion.

Washington was able to foresee all of this because the early American republic was not that different from our own time. Though the issues in the 1800 election may seem remote in 2021, Americans were no less invested in politics. Jefferson was alarmed by the way Washington and Adams had centralized control of economic policy in the federal government, such as by creating a national bank, and was convinced their foreign policies were too friendly toward Britain. He was also appalled by the Alien and Sedition Acts, which brutalized immigrants and violated the First Amendment rights of political dissidents. For his part, Adams viewed Jefferson as a libertine and radical whose ideas might push America into the bloody chaos that had overwhelmed France after the revolution of 1789. And all this vitriol was just from the campaign. After the election was decided, Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s running mate, tried to seize the presidency for himself through Machiavellian backroom dealings, prompting a serious constitutional crisis and the swift enactment of the 12th Amendment as a corrective.

None of the hostile rhetoric between Trump supporters and Joe Biden supporters in last year’s election can match the sheer bile that Adams, Jefferson and their various partisans flung at each other in 1800. The difference, of course, is that only the Republican Party, after being cannibalized and devoured from within by the Trump faction, has actually failed the ultimate test of democracy. The modern GOP produced the only president who refused to honor the American tradition of accepting defeat with grace and relinquishing power peaceably. Exactly what effect the Revolution of 2020 will have on the overall history of American democracy is not clear — but to this point, the signs are not encouraging.

More from Matthew Rozsa on the history of American politics: