According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the omicron variant is now the dominant strain of COVID-19 in the United States. Nearly three out of four new infections are from this mutant virus — an increase by sixfold from where omicron infections stood last week, and an even more startling figure considering the first reported case of omicron in the United States was less than a month ago.

Scientists have made remarkable strides in understanding the origin and spread of COVID-19, which is part of what makes the omicron variant so shocking: its origins are perplexing, as it didn’t stem from other recent prominent strains like the delta variant. The confusion around its origins creates added hurdles in terms of treating it.

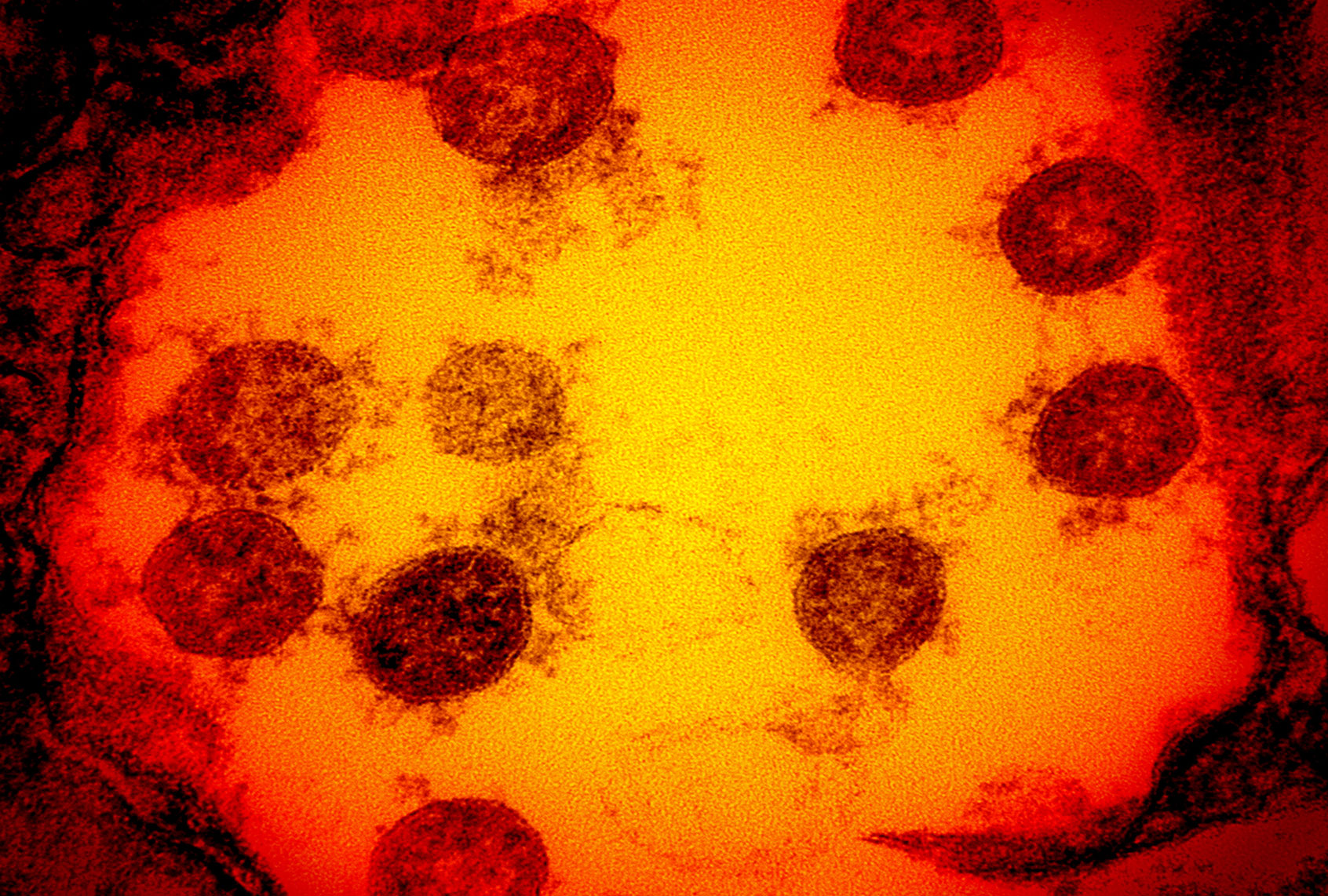

Besides being incredibly transmissible, here’s why the omicron variant is so scary: Omicron has 30 mutations located near its spike protein, which are the thorn-like protrusions on the SARS-CoV-2 virus’ central sphere. Because the existing mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are designed to train the immune system to recognize those spines as intruders, mutations on the spike proteins may help the virus evade the body’s attempts to defend itself, and perhaps partially evade existing vaccine-based immunity.

So how did omicron rack up so many mutations on its spike proteins, without any intermediate steps of evolution through other variants? Scientists have theories about how that happened, though none are comforting.

First, note that mutations are, to some degree, expected of a virus. As the novel coronavirus began to lose battle after battle to human immune systems and due to human ingenuity (vaccines), the “survivor” viruses tended to be the ones that mutated to effectively ward off human efforts at immunity. Those survivors then pass those traits to the offspring viruses it creates through replication. Thanks to genetic technology, researchers have been able to study those mutant strains and learn about SARS-CoV-2’s “family tree,” so to speak — that is, the relationship between all the variants that stemmed from one another.

Here’s where it gets weird. There is a big gap in the omicron variant’s timeline.

Sequence characteristics in any virus’ genome can be matched in databases with other strains so experts can deduce their origins. Scientists trace these family trees to learn more about a virus’ lineage, and in the hope that this information will help them defeat it. Yet the most recent identifiable sequences on the omicron variant’s genome originate from over a year ago, all the way back to the middle of 2020. This means that scientists cannot link it to currently circulating strains. Yet they know for sure that this strain is very different from the original SARS-CoV-2 strain that brought the world to its knees at the beginning of 2020.

So what explains that gap? Where did the omicron variant come from?

One hypothesis is that it developed in an immunocompromised COVID-19 patient. While there is no direct evidence that this happened, scientists do know that viruses can become stronger in the body of a person with a weak immune system, because they circulate for longer — continuing to mutate as they evade the patients’ weakened immune system. A virus that circulates for months in the body of an immunocompromised patient might be able to develop superior survival skills by developing defenses against human antibodies.

Richard Lessells, an infectious disease specialist at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, saw this in action. Lessells observed SARS-CoV-2 samples from the body of a female HIV patient (who had received improper treatment). Over a period of roughly six months, the virus adapted and changed quite a bit in her body.

“Because we had samples from a few different time points over that six-month period, we could show how the virus evolved and variants with some of the same mutations as the variants of concern appeared over time in the samples,” Lessells told NPR.

Writing for Forbes, Dr. William Haseltine — a biologist renowned for his work in confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic and currently the chair and president of the global health think tank Access Health International — observed that there have been a number of cases in which mutant variants have incubated in immunocompromised COVID-19 patients who are treated by antiviral drugs and antibodies after they could not fully shake their infections. These cases have been found in Italy, the United Kingdom and American cities like Boston and Pittsburgh.

Of course, these are merely theories — it has not been proven that omicron originated in an immunocompromised patient. These studies and theories merely demonstrate that such a development could have happened.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Haseltine also touched upon the next much-discussed possibility, which is that the omicron variant emerged from a process known as reverse zoonosis — that is, a situation in which a virus that originated in another animals jumps to humans, then back to animals, and then back to humans again. The COVID-19 pandemic originated from the first step of that process (jumping from an animal, probably a bat or a pangolin into humans), and the hypothesis is that the virus somehow jumped from a human to an animal and then back to a human.

Indeed, the SARS-CoV-2 virus has proved troubling adept at infecting animals that regularly come into contact with humans. The mink farming industry has taken a hit (quite possibly a fatal one) because of COVID-19 infecting huge numbers of the animals that are raised for their fur to feed the fashion industry. Likewise, the virus has infected dogs and cats, and American deer. Zoo animals like lions, giraffes and two-toed sloths have also gotten sick. While there is no evidence that the SARS-CoV-2 strains that entered these animals have managed to reinfect humans, that does not mean this would be impossible.

Not everyone buys that the omicron variant could have emerged that way. Trevor Bedford, a computational virologist and professor at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, told NPR that he doubts the omicron variant started in an animal because he does not see residual genetic material from those animals in its genome, but instead an insertion of human RNA. This “suggests that along [omicron’s evolutionary] branch, it was evolving in a human.”

Haseltine, by contrast, wrote for Forbes that this hypothesis is “entirely plausible, and may indeed be probable.” After pointing out the diverse number of animals that have been infected by COVID-19, he noted that such a double-transfer between species had been observed previously to lead to a new mutation in a spike protein.

Bedford also speculated that the omicron variant’s mysterious origins could be explained simply by its unknown provenance. There are large sections of the planet where COVID-19 is inadequately monitored, particularly in Southern Africa (where omicron was first detected) so a rampant strain might have evolved several times in one of those regions without being noticed — at least, not until it spread outside that area. Yet Bedford also expressed doubt about that argument on the grounds that “it would seem that as [this strain of the virus] was on its path to becoming omicron and becoming a quite transmissible virus, [the earlier versions] would have started to spread more widely before just now.”

Haseltine has also advanced the hypothesis that the omicron variant might have arisen because of human intervention. In his Forbes editorial, he suggested that a COVID-19 patient with the Merck drug molnupiravir might have inadvertently incubated the omicron variant. Molnupiravir works by inserting errors into a virus’ genetic code, making it harder for the virus to reproduce and therefore easier for the immune system to defeat it. Yet Haseltine claims that if molnupiravir is not administered properly (such as by not being taken over the full five-day period), or even if it is used correctly but everyone involved is just unlucky, it could produce a heavily mutated virus strain.

Haseltine noted that an FDA analysis of the drug’s clinical trial results showed that patients who had taken molnupiravir had more viral variation than those who did not, including 72 emergent spike substitutions or changes among 38 patients who took that drug. A Merck spokeswoman told the Financial Times that Haseltine’s “unfounded allegation has no scientific basis or merit” and added that “there is no evidence to indicate that any antiviral agent has contributed to the emergence of circulating variants.”

While the omicron variant is more transmissible than other SARS-CoV-2 strains, it does not yet appear to be more deadly. However, experts believe it will overtax America’s health care system because it will infect so many people, some of whom will inevitably become seriously ill.

“The two vaccinations, typically of any of the vaccines, offer virtually no protection against infection and transmission,” Haseltine told Salon earlier this month. “Three vaccinations offer only very temporary protection after three months.”

Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease doctor and professor of medicine at the University of California–San Francisco, told Salon several days ago that the omicron variant is “more transmissible and will cause a wave of new infections,” but added that “there is now evidence that omicron is less severe than previous strains.” She added that scientists do not yet know “if this is because of increasing cellular immunity in the population in December 2021 versus an inherent property of the strain that makes it less virulent.”

Read more on the omicron variant: