When 24-year-old John F. Kennedy tried to enlist during World War II, he was initially turned away. Although he was the son of one of America’s wealthiest entrepreneurs, Kennedy was not rejected because of connections. The doctors had a legitimate medical concern: Kennedy had a slipped disc around his lumbar spine, because the adjacent bone had inexplicably softened. Historian Robert A. Caro later wrote in “The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power” that it was “almost as if the spine had rotted away,” likely due to medical treatments Kennedy had received for stomach and colon pain. Kennedy was far from surprised by the spinal diagnosis, given that he had been suffering intense lower back pain for months. Yet instead of accepting that he would not serve his country, Kennedy used his rich father’s connections to get a dangerous assignment on Navy patrol torpedo boats in the South Pacific.

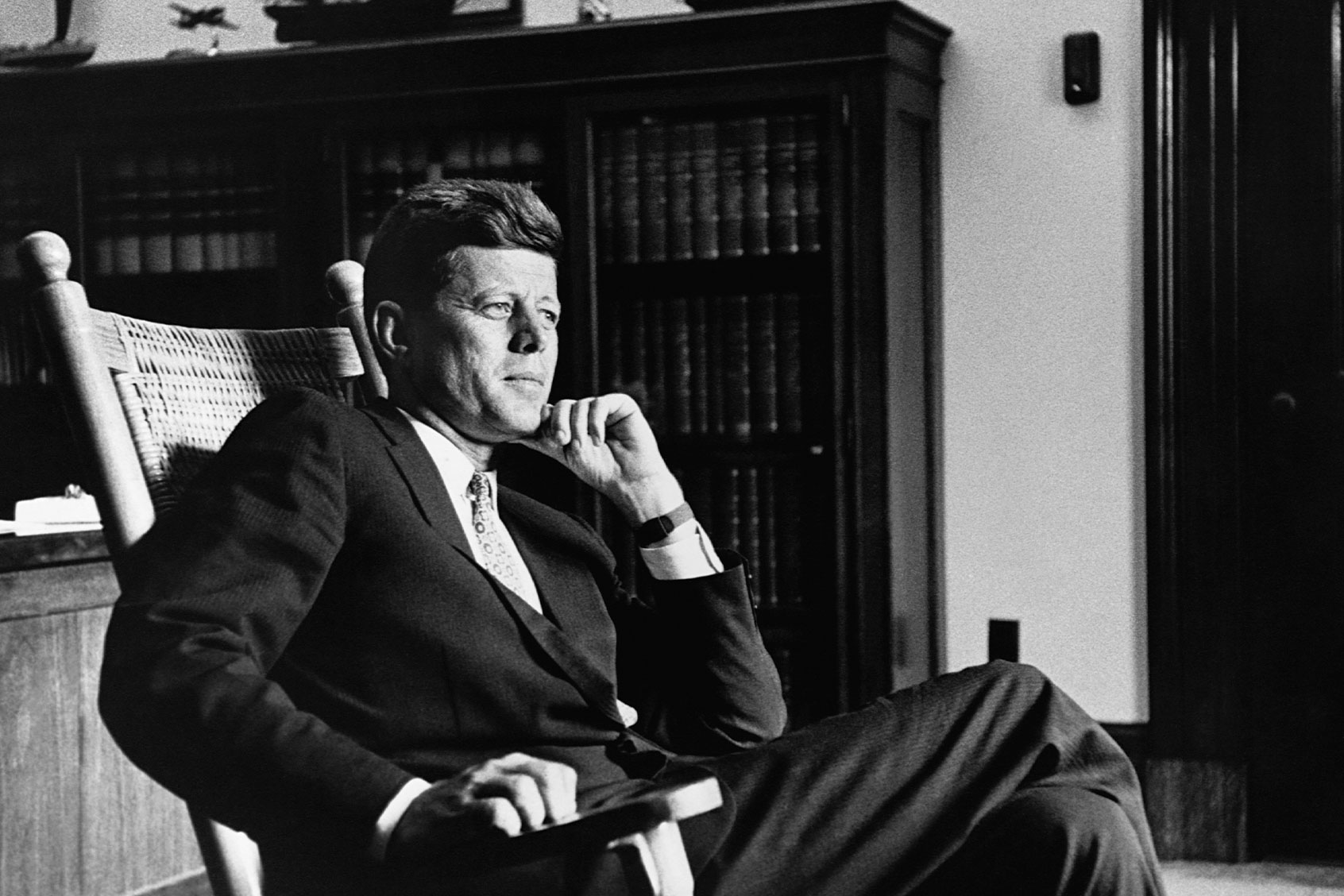

Although Kennedy is not often regarded as an icon for the disabled community, Kennedy’s story is the quintessential tale of overcoming a disability-caused adversity.

For his back pain, Kennedy had nothing but a brace. There is no doubt that, as he commanded the boat PT-109 in August 1943, Lieutenant Kennedy was in immense discomfort on the bobbing, rocking vessel. Despite this disadvantage, Kennedy proved himself a hero: When PT-109 was cut in half by the Japanese destroyer Amagiri (likely due to an intentional collision), he personally rescued three men, then led the group of 11 survivors on a mass swim to an island 3.5 miles away. (It was then called Plum Pudding Island; today it is known as Kennedy Island.) One of Kennedy’s crewmates was so badly injured that Kennedy had to strap him into a life jacket and then pull him with his teeth.

Although Kennedy is not often regarded as an icon for the disabled community, Kennedy’s story is the quintessential tale of overcoming a disability-caused adversity. Throughout his life, Kennedy struggled with constant pain, often resorting to controversial methods in order to treat it. He also had, within his family tree, a dark secret that no doubt gave him an additional sense of personal connection to the disabled community. Even as he kept his pain a secret — much like President Franklin D. Roosevelt, or FDR, had been before him — JFK fought for others who struggled because of disabilities.

“President Kennedy’s interest in the needs and rights of people with disabilities, along with the support of our organization and others, resulted in a national spotlight on the circumstances in which people with [intellectual and developmental disabilities] were forced to live,” explained Julie Ward, SEO of Public Policy at The Arc of the United States, wrote Salon. The Arc was founded in the 1950s by parents of disabled children, and Kennedy created a Presidential Panel on Mental Retardation to create momentum for important changes in national policy. Though the name of the panel would be considered offensive now, at the time it was a normal phrase to refer to intellectual disability.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“At least to a degree, [being disabled] deepened his empathy — on a cognitive level more than an emotional one — toward the sufferings of others, much as polio did with FDR.”

“The Presidential Panel on Mental Retardation in one year made over 100 recommendations that would affect the future of research, health, social services, education, care, and professional development – all of which seeded legislation and sweeping changes over the coming years at the national and state level,” Ward explained.

In addition to his work with the panel, in the final weeks of his life Kennedy signed two landmark bills into law. The Maternal and Child Health and Mental Retardation Planning Amendment to the Social Security Act (quite a mouthful) used up-to-date scientific research to improve the care for intellectually disabled people throughout the country. In addition, it increased funding for maternal and child care that could prevent the development of certain disabilities. A second bill later significantly increased funding for institutions for treating and preventing disabilities. “The mentally ill and the mentally retarded need no longer be alien to our affections or beyond the help of our communities,” Kennedy proclaimed while signing the second bill into law.

“At least to a degree, [being disabled] deepened his empathy — on a cognitive level more than an emotional one — toward the sufferings of others, much as polio did with FDR,” explains Fredrik Logevall, the Laurence D. Belfer Professor of International Affairs at Harvard University and a Kennedy biographer. In addition to contributing to JFK’s moderation of the conservative instincts he had inherited from his Wall Street tycoon father, Joseph P. Kennedy, “no doubt, too, his constant health travails fed his deepening interest as senator and then president in health care and the government’s role in making it broadly available to the American population.”

“The Presidential Panel on Mental Retardation in one year made over 100 recommendations that would affect the future of research, health, social services, education, care, and professional development”

Not all of Kennedy’s efforts succeeded during his lifetime. When JFK attempted to launch government health care for the elderly, a program that would eventually become Medicare, it flopped as his critics accused him of wanting to socialize medicine. Yet when Medicare was ultimately passed by Kennedy’s successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson, it was in no small part because JFK had prioritized the policy during his administration. One of his closest supporters in the Senate, fellow Democrat Clint Anderson of New Mexico, had also been a lifelong advocate of government-funded health programs, noting his own lifelong health issues and remarking that “perhaps a man who has spent much of his life fighting off the effects of illness acquires…an understanding of the importance of professional health care to all people.”

Of course, the reason Kennedy never lived to see Medicare brought to fruition is that he was assassinated on Nov. 22, 1963. Yet even if his life had not been snuffed out by an assassin’s bullet, JFK was so sick — and used so many volatile drugs to combat what Logevall describes as “myriad ailments” — that it is unclear whether he would survived until Jan. 20, 1969 (the end of what would have been his second term if he had defeated Republican nominee Barry Goldwater in the 1964 election). Among these conditions was Addison’s disease, an adrenal gland disease that was often fatal in JFK’s era. This contributed to his back pains, which were further exacerbated because the left side of his body was smaller than the right side. In addition, JFK would often endure bouts of ulcerative colitis.

“It was a rough combination, yet what’s interesting is how little these ailments affected him, at least in terms of slowing him down,” Logevall wrote to Salon. “On the campaign trail, he would go from dawn until after midnight, day after day, driving his aides to exhaustion, never mind that his back was killing him and he had to use crutches to get around. It was almost as though he had to prove — to himself as much as to others — that his maladies would not get the better of him.”

Kennedy did not have to rely on will power alone. As Logevall recalled, the future president began steroid therapy in his late twenties, started taking cortisone in 1949 and worked with Dr. Max Jacobson, a so-called “Dr. Feelgood” known for providing nerve-soothing pharmaceutical cocktails to celebrities from Eddie Fisher and Otto Preminger to Truman Capote and Tennessee Williams. They could include everything from amphetamines and tranquilizers to placenta and vitamins, and Logevall acknowledges that Jacobson’s role in medicating Kennedy remains “murky” today. Even so, it is known that Jacobson “provided amphetamine injections to Kennedy at various points during the White House years” and that “Jacobson’s presence caused consternation among some presidential advisers, including [JFK’s brother and attorney general] Robert Kennedy.”

The drugs were not Kennedy’s only dark secret. In 1941, when JFK was using his father’s connections to enlist in the armed forces, his younger sister Rosemary was given a lobotomy by that very same father. To this day, historians are unclear about the nature of the illness that prompted Joseph Kennedy to seek that radical treatment. We know that Rosemary was prone to seizures and fits of uncontrollable anger, some of which led to violence. She appeared to have an intellectual disability of some kind, although it is unclear what exactly it was. Her parents sent her to boarding schools for intellectually disabled children, and in her teenage years she needed to be taught separately from the other students. As her behavior worsened — including possible sexual encounters — her father was convinced that a lobotomy could end her mood swings and violent outbursts.

Instead she was rendered into an invalid. She had the intellectual capacity of a two-year-old, was incontinent, never fully regained her ability to speak, struggled to perform basic daily maintenance routines, and had a palsied arm. For years her family kept her in an institution in Wisconsin — out of sight, out of mind.

Yet was she ever entirely out of JFK’s mind?

Again, the sources are unclear. Certainly it is easy to imagine that the Kennedys as a family had increased sympathy for mental illnesses due to shame and pain over their handling of Rosemary’s situation. Rosemary’s younger sister Eunice later founded the Special Olympics and acknowledged that part of the reason why was her experiences with Rosemary. Yet even without the Rosemary saga, JFK’s own life story certainly goes a long way toward explaining why he would sympathize with people who struggle in their bodies.

Despite his image as a vibrant and healthy young man, JFK too was disabled.