Octopus minds are notoriously mysterious. Earlier this year, when scientists published a study on measuring octopus brain waves in the journal Current Biology, they were forced to admit that the results were hard to decipher; some of the waves looked similar to those in mammalian brains, but others seemed entirely alien. Back in 2021, a documentary called “My Octopus Teacher” won the Oscar for Best Documentary by chronicling one human’s attempt to understand an enigmatic octopus in the wild. It is hard to deny that octopuses are as fascinating as they are apparently inscrutable.

Yet a recent study in the journal Cell reveals something new about octopuses that was not known before: They can edit their own genetic information to alter their brains as necessary when confronted with warmer or colder temperatures.

Like the study earlier this year about octopus brain waves, this new research on octopus brain RNA raises more question than it answers.

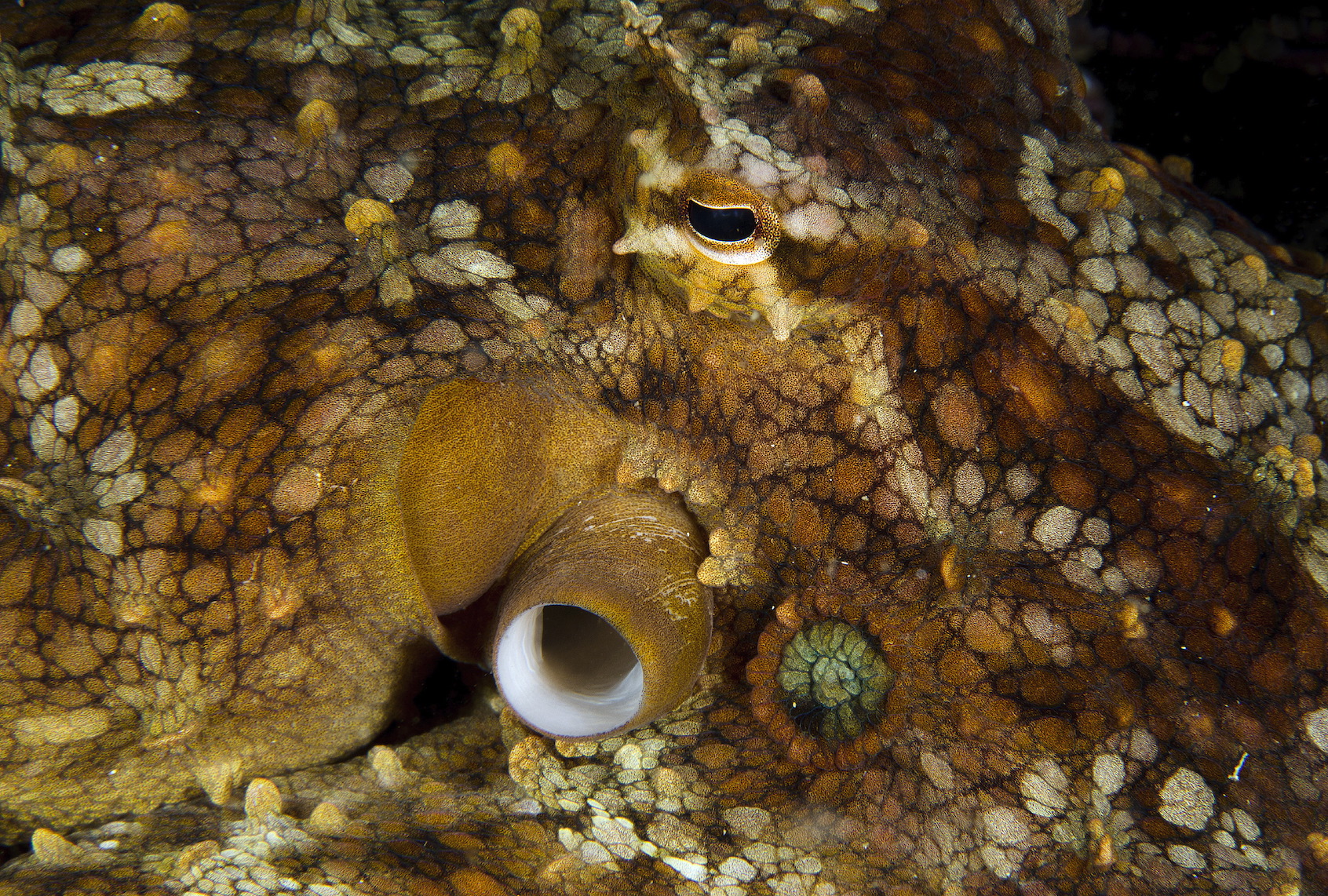

This is no simple achievement: The brain is such a complex organ that it needs to be carefully regulate its temperature in order to work. Octopuses lack skulls and other organs to naturally protect their brains from fluctuating temperatures, yet still need to accomplish this task within their squishy heads and in a constantly-changing environment to boot. To protect their brains, scientists learned, octopuses can alter their own RNA.

When it comes to genes, DNA can be thought of the blueprint of an organism’s body and RNA can be viewed as the courier, a messenger that transmits information so that this blueprint is followed. RNA usually does not get edited very much in organisms, but the scientists behind the Cell article found that in octopus brains it can get edited significantly.

To learn this, the researchers studied the California two-spot octopus (Octopus bimaculoides), which they report is “an ideal species for this study because they experience relatively large seasonal temperature changes, have a high-quality sequenced genome, and a comprehensive map of editing sites across their neural transcriptome has been constructed.”

Of course, like the study earlier this year about octopus brain waves, this new research on octopus brain RNA raises more question than it answers. The underlying mechanism spurring these changes remains unknown, but it occurs rapidly, within a few hours.

“Is temperature-dependent RNA editing used for acclimation, or is it simply a byproduct of the temperature changes?” the authors ask at one point, concluding that “a detailed examination of how recoding events affect protein function can provide critical data to answer this question.”

When concluding their discussion of the study’s results, they speculated that “due to the extraordinarily large number of temperature-sensitive events,” they expect that the effects of this RNA altering “are widespread across neurophysiological processes. Furthermore, it will be interesting to see whether RNA editing can respond to other changes in the physical environment.”

Ultimately these questions could shed light on the evolutionary pressures that helped make cephalopods what they are today.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Octopuses’ ability “to adopt high-level mRNA recoding remain enigmatic and fascinating,” the authors conclude.

Octopuses’ ability “to adopt high-level mRNA recoding remain enigmatic and fascinating,” the authors conclude.

“This study shows for the first time that in the same organism, under different conditions, it expresses different proteins from the same gene,” study researcher Eli Eisenberg, a physicist at Tel Aviv University, told NPR. “And they have different functional behavior that is presumably suited to the external temperature.”

San Francisco State University neurobiologist Robyn Cook, who was not involved in the research, told the station that she would like to learn “what types of behaviors are affected by these different types of changes — their reaction speeds, their ability to camouflage.”

These are far from being the only lingering mysteries about the minds of octopuses. In the earlier research into octopus brain waves, scientists described slow and prolonged oscillations with large amplitudes, unlike any brain wave produced by other animals. Even more bizarrely, the scientists were unable to link any specific waves to activities performed by the octopuses, immensely complicating the process of determining cause-and-effect between certain waves and specific results.

Then again, a 2021 study on octopus brains found some revealing similarities to human brains. Among many other things, they determined that octopus brains have a lot of folds — a physical trait that brains acquire through a process known as gyrification — even though this trait is usually associated with mammals and other complex organisms that need to retain large quantities of information.

Perhaps the most notable intellectual trait possessed by octopuses is their intense curiosity. This has been gleaned by scientists and other nature admirers merely by observing them.

“With such a highly intelligent creature, it’s likely to get bored,” Pippa Ehrlich, co-director of “My Octopus Teacher,” told Salon in 2021. “It wants to explore. It wants to be entertained. But it’s also completely liquid and soft. It has no physical protection against anything, apart from being able to hide in small spaces, because its liquid adds this incredible creativity that these animals have developed over time in order to receive predators and catch prey.”