Less than five minutes into her debut feature, “Bonjour Tristesse,” as faultlessly framed shots of the rippling French seaside and all of its natural wonders cascade across the screen, director Durga Chew-Bose announces herself as one of the great contemporary image-makers. For anyone who’s fitfully torn through the pages of Chew-Bose’s 2017 essay collection, “Too Much and Not the Mood” — adored equally by critics, readers and a musician you might’ve heard of called Lorde — that’ll come as no surprise. She has a knack for holding a feeling so gently that it can be examined without corruption, a method of narrative writing that feels disarmingly intimate. But for those who know “Bonjour Tristesse” as a familiar title, Chew-Bose’s film might raise an eyebrow.

The movie is, after all, the second cinematic retelling of Françoise Sagan’s classic 1954 coming-of-age novel, about a teenage girl named Cécile, whose idyllic summer in the south of France is interrupted by her father’s rigid new lover, Anne. Sagan’s novel was adapted into a film four years later, where French New Wave icon Jean Seberg put a cherubic face to Cécile’s scheming. Both the book and the film have been adolescent media mainstays for decades, which makes attempting a new version all the more bold. But Chew-Bose’s sublimely fresh take on a familiar tale is unburdened by comparisons. Her “Bonjour Tristesse” brings viewers deeper into Anne and Cécile’s stilted relationship, noting how they quietly clash despite their villa being big enough for the two of them. Their power struggle represents a conflict as timeless as the story of “Bonjour Tristesse,” one where we push against change so stubbornly that our resistance turns to cruelty. The summer sun beats down on our skin so intensely that it feels like it could last forever, but admitting that it won’t is purely unreasonable.

Every frame is constructed to look impossibly perfect, like that warm summer day you hope will go on forever. But alongside their director, Sevigny and McInerny carefully remind us that fantasy and tragedy are interlinked.

Resistance was similarly futile for Chloë Sevigny, who stars in the film as Anne. When Sevigny first read the script, she was hesitant. “I was like, ‘Do we want to reinforce this kind of trope?’ she told Salon ahead of the film’s theatrical release. Sevigny was wary of repeating the oft-told story of a middle-aged man (Cécile’s father Raymond, played here by Claes Bang) falling vulnerable to his younger lover and Anne’s foil, Elsa (Nailia Harzoune). Working alongside Cécile (a haunting Lily McInerny), Anne and Raymond’s relationship is tested by youthful, liberated femininity — the antithesis to Anne’s mature stoicism and career-first mentality. “As a feminist, I was a little concerned with that,” Sevigny continues. “Even though being 50 and seeing that happen to friends over and over, it’s just a reality . . . I have a lot of women in my life who are living that. I think it’s a profound thing to examine.”

Chew-Bose’s “Bonjour Tristesse” invites a close, crisp new look at classic ideas we think we know inside and out. She’s deeply interested in why Sagan’s story has maintained its relevance, even if parts of it feel outmoded. Far from a mere remake, her take is a gorgeously rendered, self-reflexive look at cycles as inevitable as the seasons. She wants to know why we repeat our mistakes and convince ourselves that things will be different this time, and why we resist the change that we know will come for us eventually. To do that, Chew-Bose has made a film so jaw-droppingly chic that viewers can’t help but want to live inside of it. Every frame is constructed to look impossibly perfect, like that warm summer day you hope will go on forever. But alongside their director, Sevigny and McInerny carefully remind us that fantasy and tragedy are interlinked. Come autumn, the sun-soaked July mornings will be long gone, and all that will be left are the memories we held onto before they slipped away.

Chloë Sevigny as Anne in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). For McInerny, whose effusive grace is a noticeable contrast to Cécile’s boastful assuredness, time on location in Cassis before filming was essential for inhabiting her character’s demeanor. “A lot of the character work I was doing alongside Durga was in Cécile’s physicality,” McInerny says. “The way she moves through space with an almost genderless and childlike recklessness at the top of the film, and then the way her physicality changes once Anne arrives and becomes an aspirational figure as well as a threat to the version of myself I once was.” From the film’s opening frames, depicting Cécile coasting the crystal blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea alongside her summer fling, Cyril (Aliocha Schneider), Cécile is soaked in respite. Despite some low marks in her final years of high school, she’s unworried and unhurried, content to spend her days gazing at the water or dozing on the beach.

Chloë Sevigny as Anne in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). For McInerny, whose effusive grace is a noticeable contrast to Cécile’s boastful assuredness, time on location in Cassis before filming was essential for inhabiting her character’s demeanor. “A lot of the character work I was doing alongside Durga was in Cécile’s physicality,” McInerny says. “The way she moves through space with an almost genderless and childlike recklessness at the top of the film, and then the way her physicality changes once Anne arrives and becomes an aspirational figure as well as a threat to the version of myself I once was.” From the film’s opening frames, depicting Cécile coasting the crystal blue waters of the Mediterranean Sea alongside her summer fling, Cyril (Aliocha Schneider), Cécile is soaked in respite. Despite some low marks in her final years of high school, she’s unworried and unhurried, content to spend her days gazing at the water or dozing on the beach.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

But these long, hot days are just mimicry. Like most teenagers, Cécile has no idea who she is or who she wants to be. She’s mirroring her father and Elsa, who spend their time lounging, cooking, reading, swimming and sleeping. It’s a charmed life, and as such, totally impractical, as Anne notes when she arrives at Raymond’s behest. An old friend of Cécile’s late mother, Anne’s days are spent designing couture for high-paying clients; sharp, angular garments that find beauty in the construction and hard work. Hers is a success that’s earned, but that doesn’t mean it’s not lonely. Creating such stunning clothing is demanding work that has left Anne little time for anyone else, something Sevigny — a modern bon vivant if there ever was one — says felt true to her life. “[I have] friends that are so committed to their art that, for some reason, they never found the right partner or never decided to commit to having a family,” she says. “Now that they’re older, they’re second-guessing their choices. Playing a character [who has both] strength and restraint, I didn’t feel like I had ever played before.”

Anne’s arrival at the villa is a crossroads, a rare opportunity to choose a new path toward something she hasn’t yet experienced: real, tender love. Though she doesn’t come to Cassis anticipating romance. “I can hold onto my loneliness and still love enormously,” she tells Raymond one afternoon. “I’m very good at doing both at the same time.”

Chloë Sevigny as Anne in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment)Even so, her appearance sends a ripple through the established unit of Raymond, Elsa and Cécile; not because Anne’s necessarily a competitor for Raymond’s affection at first, but because she reminds the trio that life is not all buttered toast and lazy mornings. The thing about eternally enjoying the spoils of life? It gets boring. Our brains crave an outlet for thinking and creativity, more than just the buzz we get from reading a novel while the sun sets over the sea. Anne is an early winter, and Raymond is taken with the idea of a stability that will last long after the summer has ended.

Chloë Sevigny as Anne in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment)Even so, her appearance sends a ripple through the established unit of Raymond, Elsa and Cécile; not because Anne’s necessarily a competitor for Raymond’s affection at first, but because she reminds the trio that life is not all buttered toast and lazy mornings. The thing about eternally enjoying the spoils of life? It gets boring. Our brains crave an outlet for thinking and creativity, more than just the buzz we get from reading a novel while the sun sets over the sea. Anne is an early winter, and Raymond is taken with the idea of a stability that will last long after the summer has ended.

This all sounds like it might ramp up into some shocking explosion. In another filmmaker’s contemporary imagining of “Bonjour Tristesse,” it might. These are the days of Bravo cheating scandals and TikTok fight videos; audiences expect drama and devastation from an immediate and severe fallout. But Chew-Bose’s film is unencumbered by the expectations we’ve developed in modern life. “Bonjour Tristesse” is intentionally slow and quiet. “The pacing [feels like] the content and setting of the languid summer vacation and the time warp you enter,” McInerny says after Sevigny mentions their director's leisurely tempo. Chew-Bose directs viewers to settle into the film’s rhythm, which feels almost analog, recalling a time when our immediate references for human behavior weren’t 60-second vertical videos. Outside two brief shots of Cécile queuing up a song or taking a photo with her phone, Chew-Bose’s “Bonjour Tristesse” could be set outside of time entirely.

This transcendence is one of the film’s greatest gifts, a chance to practice serenity and patience when there is little of either. Chew-Bose makes plenty of space for life’s mundanities. We watch as Anne sections a pineapple and pages through the morning paper, and as Cécile rests on the beaches and in her bed, letting the anxieties pour out of her. Under Chew-Bose’s direction and cinematographer Maximilian Pittner’s singular eye, we are allowed to appreciate the tranquility of existence. And yet, Chew-Bose innately understands how to weave meaning into each carefully crafted shot. Every frame is intentional. The camera blocking is acute and almost frustratingly perfect. Every meticulous detail — from Anne’s tailored pleats to how each woman eats an apple — is beguiling. How can anything look so magnificent? It’s consuming. No wonder Cécile wants to bask in it for as long as she possibly can.

Lily McInerny as Cécile in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). But even all that beauty and precision can’t protect us; they can’t keep life from moving forward. Elsa knows that as well as Anne does, and she reluctantly accepts when Raymond tells her he’s engaged to Anne. The two women work out their differences like adults. Raymond’s drifting affections aren’t easy to grapple with, but the pain comes with life, and Cécile hasn’t lived enough of it to understand that. The breakup signals the end of her vacation before its natural conclusion. When you’re young, you’ll do anything to make summer last a little bit longer.

Lily McInerny as Cécile in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). But even all that beauty and precision can’t protect us; they can’t keep life from moving forward. Elsa knows that as well as Anne does, and she reluctantly accepts when Raymond tells her he’s engaged to Anne. The two women work out their differences like adults. Raymond’s drifting affections aren’t easy to grapple with, but the pain comes with life, and Cécile hasn’t lived enough of it to understand that. The breakup signals the end of her vacation before its natural conclusion. When you’re young, you’ll do anything to make summer last a little bit longer.

“The articulation of artistry is always a little cringey. It’s very hard to do," Sevigny says. "And I remember I kept fighting Durga on it, not really wanting to do it. ‘Can we maybe rewrite it, or how can we get around it?’ I just decided to commit and do an interpretation of Durga. That’s truly her.”

In trying to convey this feeling in the film’s centerpiece scene — newly written for her version of the story — Chew-Bose achieves something remarkable. She brings an intimacy out of her actors that acts as a mirror, reflecting their director’s soft, sweet manner for the viewer. The camera peers at Anne as she looks over sketches for her new collection. The drawings are lush and vivid, sketched with sharp lines and colored with deep red and yellow. Cécile joins her, and Anne asks her opinion. “I like this one,” Cécile says, pointing to a sketch of a woman whose arms are adorned in large fabric roses. “It feels…” Anne says, before Cécile chimes in. “…Free.” Anne corrects her: “Unthinking.”

Initially, it seems as though Chew-Bose is taking a surface-level approach to illustrate the differences between these two people, a departure from how cleverly she’s relayed these variations until now. But Anne continues, “I count on these unthinking gestures, otherwise the work becomes really boring, really bad. The moment things become forced, I question everything. Sometimes I think the point is to know less and less. If I’m creating clarity or meaning, I lose interest. There always has to be a third thing. I don’t know how to talk about it, it vanishes before I can grab hold of it.”

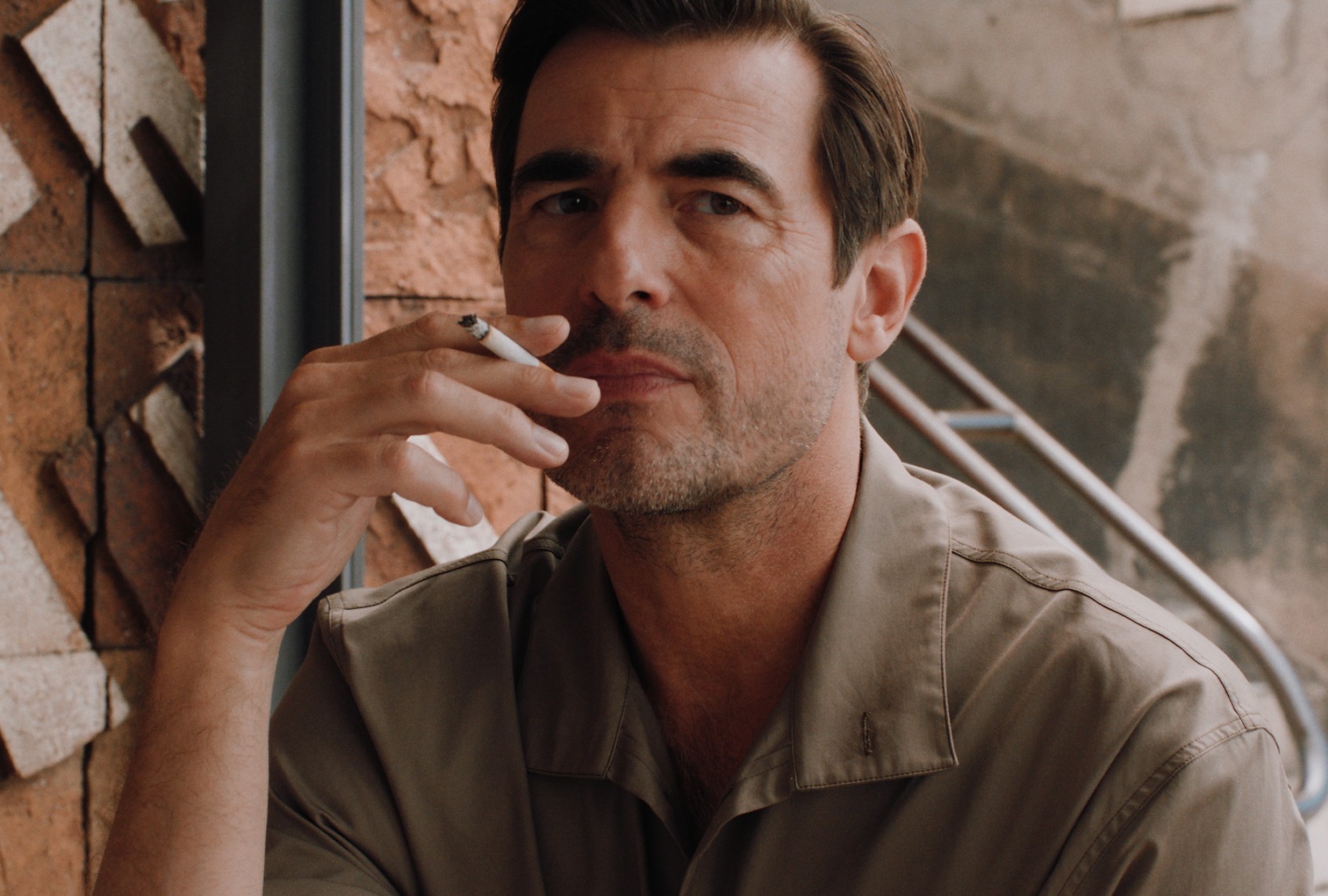

Claes Bang as Raymond in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). When I ask about their memories of shooting this scene together, McInerny and Sevigny recall that it was awkward, even difficult. “That was one of the harder pieces of dialogue,” Sevigny remembers. “The articulation of artistry is always a little cringey. It’s very hard to do. And I remember I kept fighting Durga on it, not really wanting to do it. ‘Can we maybe rewrite it, or how can we get around it?’ And I just decided to commit and do an interpretation of Durga. That’s truly her.”

Claes Bang as Raymond in "Bonjour Tristesse" (Courtesy of Greenwich Entertainment). When I ask about their memories of shooting this scene together, McInerny and Sevigny recall that it was awkward, even difficult. “That was one of the harder pieces of dialogue,” Sevigny remembers. “The articulation of artistry is always a little cringey. It’s very hard to do. And I remember I kept fighting Durga on it, not really wanting to do it. ‘Can we maybe rewrite it, or how can we get around it?’ And I just decided to commit and do an interpretation of Durga. That’s truly her.”

"Our characters are at such different points in our lives,” McInerny adds. “But that was the closest we ever came in the film to being mother-daughter. It was a challenge, attempting to articulate this very abstract concept of creativity and unnameable inspiration."

But by just endeavoring to put a feeling to words, Chew-Bose, Sevigny and McInerny capture the essence of “Bonjour Tristesse,” and our human desire to characterize something inexplicable. The times change, but our struggle to give meaning to joy, love, heartache and eternity never will. We want every summer to be significant, to be the time we sweat out the rest of the year’s uncertainty and experience so much life that we can take it with us when the season’s over. Like Anne, we try to grasp this nameless, formless feeling before it drifts away. But it always does.

Read more

about other films that capture one unforgettable summer