Hong Kong, 1941. Newly-wed Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn floated into Victoria Harbor on a Pan-Am clipper. She was to cover the Sino-Japanese War for “Colliers Magazine,” and he was the unwilling companion, or U.C., lovingly nicknamed by Gellhorn. Though she noted in her memoir, “Travels with Myself and Another,” that he was also “better at the glamorous East” than she, “flexible and undismayed.” Hemingway was fresh off selling the movie rights to “For Whom the Bell Tolls.” At the height of his fame, money in his hand, and ripe to live like royalty. The Prince of Hong Kong, as it were, albeit for a couple of months.

We come to this Pearl City with his footprints in our pocket, ready to discover where he planted them.

The sky darkens as we stand on the corner of Queen’s Road and Pedder Street in Central. Today’s glass and steel tower over the bones of what was once the grande dame of colonial luxury, the Hong Kong Hotel. The waterfront then just a block behind, our couple strolled from seaplane to their suite to begin their first foray into Asia. Surrounded by imperial charm, palm trees and wartime tension, Hemingway quickly found his niche.

The hotel’s lobby bar called The Gripps was made for a tough, hard-drinking, worldly crowd of voyagers, tucked into the far corner of an empire. This became his nightly perch.

The pair met “a maddening, intriguing, colorful world of dictators and drunks, scoundrels and socialites, heroes and halfwits,” per Peter Moreira in “Hemingway on the China Front.” Ernest, being Ernest, quickly fell in with many on the list. Those who trade stories to match pace with endless whisky sodas and hubris. He called them his “Hong Kong millionaires.” One proved to be a favorite for Hemingway, Morris “Two-Gun” Cohen. A fellow globe-trotting adventurer, game hunter, storyteller, and an old bodyguard to Sun Yat Sen. The closest thing to a soul mate he found in town.

Whether it was Gellhorn’s “groaning and sighing steadily” over Hemingway’s nightly revelry or her general distaste for narrow rickshaw-packed streets and “the sheer numbers, the density of bodies”, the pair shifted operations from Central to the relative emptiness of Repulse Bay. We’ll get to that later.

It’s possible the hotel was also happy to bid them farewell, given Hemingway’s conversion of their suite into an impromptu boxing ring with an indoor firecracker habit to boot.

(Howie Southworth) Luk Yu Teahouse

Each night after tall tales and a fair bit more than a tipple at The Gripps, passing on the expected scotch eggs and roast beef at hotel’s Grill Room, the gang would head for an adventurous Cantonese feast. Hemingway “swearing they’d been served by geisha girls,” according to Gellhorn. So we follow suit along with our own thirst.

Luk Yu Teahouse on Stanley Street is emblematic, iconic even, and most importantly, close to the erstwhile hotel. When they served their first steamer of dim sum in 1933, a refined ambiance drew the elite clientele of the era. Though there’s no direct line between Hemingway and Luk Yu, it was the popular spot for an entourage such as this, so it’s the odds-on favorite.

We need your help to stay independent

Through the weighty door lives Hemingway’s heyday — but for all the Instagram posts. The wood is dark and heavy, floor tiles worn as if they remember every shoe that’s passed. Waiters float about in starched whites under slow fans and amber lights. Tables thick with steam, clamor, and the smell of curiosity. Our order walks the line between Cantonese classics that would suit Hemingway’s taste and dishes that surprise then please.

Roast pork belly redolent and tender as Castilian suckling pig. Succulent shrimp wrapped in a scant blanket of starch that would bring him back to Havana. Velvety chicken reminiscent of a Parisian poulet. All manner of poultry, game, seafood and vegetables stuffed into fluffy white buns. Shape and aroma be damned, these were his dishes dressed up in ginger and bamboo. On special is an abalone soup, an alien beast in his time, and not our cup of tea, but they say Hemingway took a shine.

Hemingway chose to dive deep into Hong Kong, especially at a meal like this, at a table like this, with a crowd like this.

On wine, missing were his beloved Spanish reds. An expensive French bottle? Sure enough, even back in the 40s, someone had a stash, and the needy paid through the nose. Hemingway chose to dive deep into Hong Kong, especially at a meal like this, at a table like this, with a crowd like this. In place of fermented grapes stood yellow rice wine, incendiary sorghum liquor and, if the night was long enough, out came a bottle of the latter infused with snake bile, promising virility. Peak Hemingway in a bottle. We opt for puerh tea, a Luk Yu specialty.

We head back out into the night, the rain’s begun, and soon we feel the old stone slabs of Pottinger Street under us. They’re slick when wet. Trinket vendors with whom Hemingway found a passing repartee still line the sides. There is very little else that remains of Hemingway’s Hong Kong at ground level. Streets repaved, sidewalks repointed, shorelines reformed. But these planks of granite lined Pottinger in the 1850s and tilted and dented with time. Millions of feet have fallen on them, and his were surely two. The most authentic moment of our route. That and roasted game birds hanging behind glass. Onward.

(Howie Southworth) Game birds, roasted and displayed

We’re told we must pay a visit to The Old Man, a Hemingway-themed bar a few blocks away. Up the steep part of Aberdeen Street and down a narrow staircase into an equally narrow alley, we find the nondescript door marked only by an illuminated hanging sign at the bottom of the stairs. The interior is chic, minimalist. Old books, some obscure, exotic liquors, and bar menus from around the globe line a few shelves on the walls. The drinks, complex and perfect. A stone mosaic of Papa’s mug dominates the rear wall, it’s abstract. Hemingway would never have drunk here, although the fanfare upon his entry may tip the scales.

This is a tribute bar, to be sure. But not to bullfights, bullets, or bravado. The tribute is to the challenged mind of a genius. The menu is like a novel about a complicated man, and mixology to match. We meet Art, one of the bosses here. Voluble and deep, an artist in his own right. He calls their menu “a progression from balance to freedom to chaos,” and talks of a drink called “Expert of Danger.” It spins the tale of Hemingway the hunter. A jar is filled with hay, then the hay is burned, the mix including pine cone jam and pomegranate is poured inside. A foretelling of last earthly smells, whether for the hunted or the hunter. “It’s pretty dark,” admits Art.

As a last gesture, and to lighten things up, Art orders up two refreshers, one a classic Papa Doble, a fine sip, said to have been invented by or for the man in Havana, and one they dub “The Hemingway Daiquiri,” built stronger and slightly more bitter. All quite fitting.

Now slightly askew, we ascend many stairs and descend many hills from The Old Man and cross the harbor toward Kowloon. Our lodge is not The Peninsula Hotel, but it’s not far. It’s not a proletariat hostel, but it’s in the right neighborhood. The Mira Hotel is a contemporary stay in the heart of Tsim Sha Tsui, and Hemingway never slept here, but we enjoy a nightcap as he would. We sip and think about the Spanish Jesuit missionaries who filled this spot long before it was a hotel. Spain and that old Catholic guilt. Two things that followed Hemingway across the world. They ran in him like rivers of red wine. We raise a glass, a sacrament.

The next day brings humidity but thankfully no rain. It is far from cool. Nonetheless, we take a page out of Hemingway’s book and leave The Mira “as soon after first light as possible.” We can only imagine the sun through this thick air. But it is there, we’re assured. Breakfast is next and cha chaan teng seems to be the move. These Cantonese-style diners cropped up after World War II as a way for locals to enjoy an East-meets-West refueling, and eggs-on-bread options abound. Hemingway missed out on the trend.

One of his creations for a typewriter-friendly bite was sliced onion and peanut butter on white bread, nothing fell apart. A popular and packed cha chaan teng just around the bend serves up something just like it. We order this onion-omelet sandwich held together by peanut butter and bolstered by a strong black coffee. Strange but good. Corned beef, egg, and cheese on a soft roll, cold slab of butter on a warm “pineapple” bun. These places stay competitive with such inventions and the rulebook is always evolving. This time, right in Hemingway’s favor.

Breakfast in the rearview and the city slowly rising around us, we trace Hemingway’s footsteps into one of his more peculiar Hong Kong habits: the track. The sport of kings to some, the sport of paupers for most. Invited by then American Consul General Addison Southard, Hemingway’s first visit proved the beginning of a habit. Like the rest of colonial Hong Kong, that habit saw heavy betting matched with equal parts meat pies and cheap dim sum. And like the rest of modern Hong Kong, that menu met the decades with growing diversity, culminating in choices from fast food burgers and tapas to black truffle potstickers and wagyu beef sliders.

We order this onion-omelet sandwich held together by peanut butter and bolstered by a strong black coffee. Strange but good.

There are no races this day, but from my roadside perch, the vacant track below verdant hills is a sight. Gazing across to the grandstand, it’s easy to spot the memory of Hemingway in his locally-tailored “racetrack jacket,” pickpocket-proof to combat the greedy, his colorful entourage, thundering hooves on matted grass, cursed betting slips being tossed, vendors shilling beers weaving the crowd and wisps of cigar smoke, cheers and despair rising above. Happy Valley used to be covered in gravestones. Plenty more ghosts to see if we stick around.

Over the green hills, we meander beyond Happy Valley to find Repulse Bay. A relief from the urban heat, and like the Hemingways before us, respite from the throng of humanity called Central. Shortly after arriving here, Gellhorn returned to the China front and once again left Ernest to be Ernest, this time with an ocean view and manorial comforts, with a bearable touch of pretension. And Ernest he was, writing in the morning, hiking the lush seaside overlooks in the afternoon, maybe bagging a pheasant or two with “Two-Gun” Cohen, and entertaining in the evenings at the bar. Time drove the old hotel here to the ground as condos rose, but the bar and restaurant wing remains, The Verandah.

Ceiling fans turn lazily above the afternoon dining room, open to the breeze in Hemingway’s day, now glassed-in. The view remains stunning. We settle into rattan chairs overlooking the South China Sea. In 1941, Hemingway sat feet away, entertaining war correspondents, expatriates, and political notables. Some say he spent most tea times with New Yorker reporter Emily Hahn, two legends living legendarily, sharing tales over cucumber sandwiches, curried prawns, scones with clotted cream and strong black tea. Standard fare for the colonial elite. That is, until the gin gimlets started to flow at sundown. “The tipple of Hong Kong,” according to Hahn.

The menu has evolved into a contemporary affair, though our lunch still hits Hemingway’s seaside obsessions. Crunchy and smooth shrimp croquettes, bright and flaky Basque ham and asparagus tarts, briny confit tuna and conserved-tomato toast, crisp then juicy, and pistachio white chocolate mousse. Hemingway didn’t cave much for desserts, but this is irresistible.

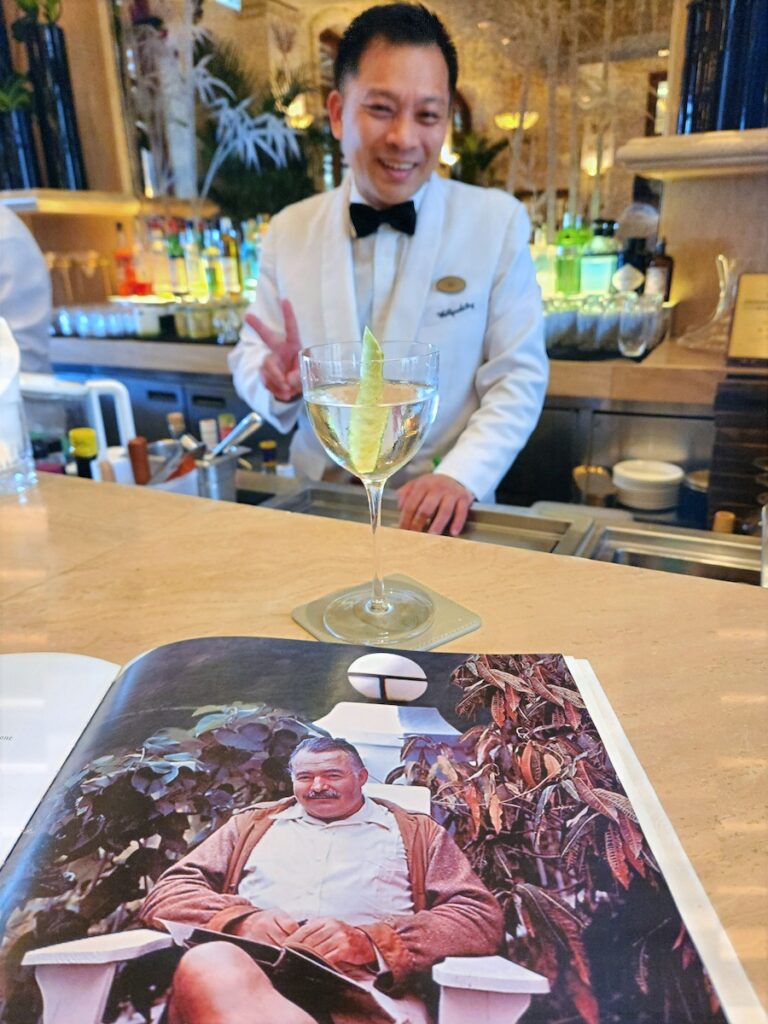

We move to the bar and sip the expected gimlets, expertly poured by the bar captain Joe Chan. His eyes perk when we mention Papa, and he leads me to a small salon. A glass case holds a shrine to the man, a painted portrait, photos, a borrowed typewriter. Hemingway visits around the globe, even brief, often left a trail.

(Howie Southworth) Bar Captain Joe Chan, a Hemingway fan, at The Verandah restaurant

Gellhorn finally persuaded Hemingway to leave the comforts of Repulse Bay and journey to mainland China and the real war. Myth may say Hemingway was sent to Asia as a spy. To the extent this was true, whatever intelligence he was able to collect on a barstool in Hong Kong paled in comparison to his boots getting muddy in China. Visits to the front, rousing of troops, evading rampant typhoid, enigmatic encounters with notable leaders like Republican Chiang Kai-shek and Communist Zhou Enlai. If any intelligence was gleaned, it would have been on the deep divide between these two men trying hard to collaborate while defeating the Japanese. But, we digress.

Amidst the chaos of war, Gellhorn and Hemingway dined with Chinese generals in Chonqing, feasting on spicy Sichuan dishes, many of the usual suspects unsurprisingly from Hemingway’s playlist – smoked duck, braised pork, real kung pao chicken buried in mounds of red chile. Guangxi, their second stop, enjoys a cuisine that celebrates wild game, which would scratch Hemingway’s itch in another way. Throughout, he toasted his hosts with baijiu, a fiery clear liquor. Hemingway, ever the raconteur, regaled the cadre with stories, matching them drink for drink of this local elixir until the nights blurred into memory. Hemingway, remembered by Gellhorn, “planted on his feet like Atlas.”

The harsh realities of the mainland wore on him, and soon he returned to Hong Kong, seeking solace in the familiar surroundings of The Bar at The Peninsula Hotel. When not at The Gripps, The Verandah, or the racetrack, Hemingway soaked himself in the glow of the regular gaggle of journalists here, his personal happy valley. Contented, he lodged the last of his Hong Kong nights at The Peninsula before returning to the US, separately from Gellhorn. After our afternoon of clean salty air at the Bay, we too end here. One final cocktail to remain salty, a Bloody Mary.

After all, Papa laid claim to debuting this concoction in the East on this very spot.

He wrote: “I introduced this drink to Hong Kong in 1941 and believe it did more than any other single factor, except perhaps the Japanese Army to precipitate the Fall of that Crown Colony.”

Read more

about this topic