Have you ever tricked yourself into seeing a non-existent cockroach in your kitchen?

Your hand catches the light just so, casting a shadow into a seldom-examined corner. Something malicious and alive, an indicator of a deeper rot, has crept into your space while you weren’t paying attention, your pest-wary hindbrain yells. A closer look reveals nothing is wrong; your kitchen is as safe as it ever was, but the shredded-nerve feeling lingers.

“Artificial Angels” captures the pummelling wrongness of internet-assisted living in 2025.

That’s the closest feeling I can come up with to watching the music video for Grimes’ “Artificial Angels.” The clip’s endless array of establishing shots will be familiar to anyone who’s had to watch a generative AI demo reel. The Canadian electropop artist dances alongside a mutating array of Grok’s virtual AI companions. Cavemen smoke cigarettes branded with the OpenAI logo. Erratic overlays of cartoon imagery mimic the brain-pummelling effect of videos created by chronic masturbators who fetishize information overload. The song begins and ends with an intentionally primitive AI-generated voice saying, “This is how it feels to be hunted by something smarter than you.”

The song and video should be something that can be observed and put aside. Shocking in the moment and forgotten before the day is out, like a dead animal spotted on a morning walk. But the bad vibes of “Artificial Angels” persist, not just because the name does what it can to cheapen Grimes’ 2015 masterwork “Art Angels,” which sees its tenth anniversary hit this very month. The sickness sticks around, in part, because we can never really leave the world Grimes is putting forward in her video. “Artificial Angels” captures the pummelling wrongness of internet-assisted living in 2025. To be online and aware is to be whacked over the head with clips of bloody conflict, obvious grifts and dogbrained tech that boils the oceans to create shareholder value forever.

That Grimes would turn that perverse feeling into a party is no surprise. The artist born Claire Boucher has always reflected the internet back at itself. If that makes you a little sick, if the whole thing feels a little unclean, that’s only because the internet has become a nauseous, infested place.

(Arturo Holmes/MG21/Getty Images) Grimes attends the 2021 Met Gala

“See you on a dark night”

Let’s back up, though. If you didn’t spend your formative years reading hastily penned blogs that ended with .mp3 embeds of dubious legality, it’s possible you don’t know who Grimes is. If your main interaction with independent musicians comes when they win a surprise Grammy, who the hell is Bonny Bear?-style, it’s likely you’ve only heard of Grimes via her relationship with the richest man in the world.

It can be hard to remember now, but the internet was still a place you went to in 2012. Bloggers passed on their latest favorites like a prophet in the town square, coming in from the online wilderness of music piracy’s heyday with new tracks that could change your life. Twitter was still a place for the early adopters of phone addiction: former forum-dwellers, professional athletes and journalists. The short-form video format and the endless scroll it helped normalize were still a ways off. Most social media platforms had yet to be fully algorithmized, making the process of logging on still feel like a conversation with distant friends and not a shouting match with billions of people.

This was particularly true on Tumblr, a microblogging platform that lowered the barrier to entry for would-be critics to share their latest fascination. The site facilitated the creation of niche fandoms via an interface that mimicked the intimacy of a passed-note conversation at the back of the class. It was a place to share obsessions that, true or not, felt separate from the wider world.

Grimes’ self-produced album came from fully immersing herself in the computer around this time. She holed up in her Montreal apartment with her laptop (and, according to lore, a healthy diet of amphetamines) to record what would be “Visions” in just three weeks. The album reflects this cloistered state. It’s synthpop swells and arpeggios feel like a pure-white LCD sunrise over a William Gibson landscape. Grimes’ filtered coos and hushed vocals approximate cybernetic birdsong. The music video for the stand-out track “Oblivion” highlights the still-extant divide between the computer world and the outside. The pink-haired Grimes dances and smiles in a heavy coat or a Hypebeast hoodie at football games and motorsports events, looking like a visitor from another planet among hordes of shirtless, rowdy men who treat the phenomenon of realizing you’re on camera with something like novelty.

Visually and musically, Grimes was holding up a mirror to Tumblr aesthetes. These diehard subcommunities centered around outre fashion, indie pop and stylish photography took to Grimes, knowing it allowed them to finally become fans of themselves. An internet obsessive and technologist, Grimes knew that she’d struck a vein of something real in the substanceless expanse of the internet. “This is a pretty good representation of the beginning of the future,” she said.

(Francine Orr / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images) Grimes at The Theatre at the Ace Hotel on Wednesday, Sept. 13, 2023, in Los Angeles, CA

“I’m only a man, do what I can”

In 1995, British theorists Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron noticed a seemingly paradoxical blend of hyper-capitalist striving and hippie utopianism that had cropped up along the West Coast of the United States, particularly in Silicon Valley and San Francisco. Dubbing it “the Californian Ideology,” they argued that the “new faith” blended the “freewheeling spirit of the hippies with the entrepreneurial zeal of the yuppies.”

While speaking in the “free to be, you and me” language of liberatory leftists, ideological proponents actually pushed forward the cause of neoliberalism through their celebrations of corporate success. Per Barbrook and Cameron, espoused beliefs in a stateless and fully individualized future promised by the creation of ever-faster interconnected networks and cheaper personal computing technology were ultimately secondary to the creation of an “electronic marketplace.”

Grimes flipped cheerleader routines into an overwhelming bitcrushed force, burying them in a maelstrom of bleeps, bloops and primal screams that sounded like the optimism of Silicon Valley crashing down around her ears.

“West Coast ideologues have embraced the laissez-faire ideology of their erstwhile conservative enemy,” they wrote. “[They are] mesmerised by their enthusiasm for the libertarian possibilities offered by new information technologies.”

20 years and a dotcom crash later, the mood in Northern California was still much the same. Major players like Facebook and Google promoted platitudes about unfettered access to information and instant connectivity to friends and neighbors while privately crafting silos to push users toward avenues they could monetize. A significant chunk of the world’s population was on social media, so few people bothered to kick the tires on the app’s massive valuations. The Cambridge Analytica scandal was still on the horizon. Facebook’s cooked books and the pivot-to-video wouldn’t prove to be a mirage for a few more years.

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

At the tail-end of the technooptimist spike brought by President Barack Obama, this was the last gasp of Web 2.0. The last real moment before an algorithmic clampdown that an artist could use the internet to blow their personality to kaiju levels and set it loose on the general public. It was in this milieu that Grimes settled down to make her “California album.”

For the unfamiliar, a “California album” is pretty much what it sounds like. Typically, the follow-up to a breakout success from an East Coast act, the California album finds the artist with a lot more money and sunshine. They get clean, they drink smoothies, they unclench their jaws for the first time in years. While you’ll never find tracks like “laughing and not being normal” or “Kill v. Maim” on algorithmically generated “breezy SoCal summer” playlists, the effect of a bigger budget and some fresh air is obvious. Grimes’ vocals still dart and jab around most tracks, but tracks like “California” carry the unmistakable, self-assured delivery of a person who just started making their own granola.

Even out west, Grimes was still Grimes, and her interest in the internet would not be denied. She flipped cheerleader routines into an overwhelming bitcrushed force, burying them in a maelstrom of bleeps, bloops and primal screams that sounded like the optimism of Silicon Valley crashing down around her ears. Once again, her reflection of the internet showed us a bit of the future. The utopia of free credit wasn’t long for the world, and the social media platforms built on it would soon become a pit of snakes, ushering in an era of dull and dangerous personalities.

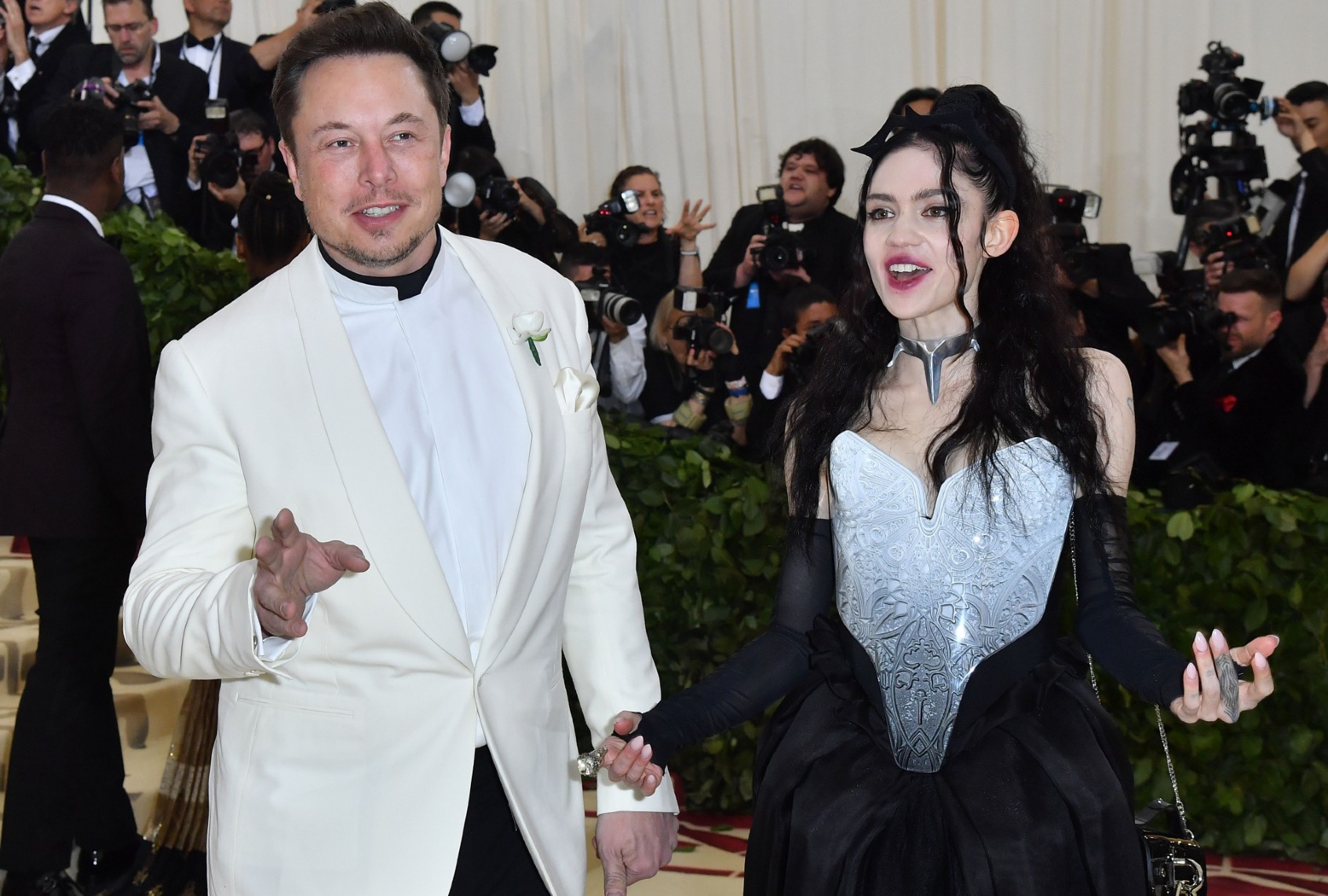

(ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images) Elon Musk and Grimes arrive for the 2018 Met Gala

“The world can only end one way”

We’ve reached the era you don’t have to strain to remember. Facebook advertising helped give us the presidency of Donald Trump. Google search became nigh unusable. Local papers faltered as the tech platforms hoovered up their advertising dollars. Even more fell when those platforms sold them a lie.

It’s possible that the discomfort that comes from Grimes’ enshi*tified output is intentional. She’s earned enough grace over several just-ahead-of-the-curve albums for us to believe that the celebratory all-out AI assault of “Artificial Angels” is not earnest.

The internet went from striving for frictionlessness to being actively hostile toward users, in a process known as “enshi*tification.” Coined by author Cory Doctorow, it refers to the process of intentionally making your user experience worse in service of serving more ads or shepherding them toward a desired outcome. Technofuturists still in California first created fake money and then fake fine art to fill the void left by the end of the ZIRP era. More and more platforms enshi*tified.

The hippies who promoted the Californian Ideology had long since fled the scene, leaving people like Musk and Peter Thiel to logic-puzzle their way into Pascal’s Wager and revive millennia-old fears of the Antichrist. Musk met Grimes while trying to make a dad joke about Roko’s Basilisk, a thought experiment about an all-powerful future artificial intelligence that punishes past critics via time travel. (It’s as stupid and circular as it sounds.) After falling in with the world’s richest man and his cadre of entrepreneurs looking to create a powerful artificial intelligence via massive energy and water usage, Grimes released a playful satire of the climate crisis in 2020 that painted the end of the Anthropocene Era as a good thing.

We need your help to stay independent

After Grimes and Musk split, he memed his way into being forced to buy Twitter for way too much money. He tweaked the algorithm honed over decades to favor fanboy cranks who promoted his cars, space colonization dreams and white supremacist fantasies. The artificial intelligence platforms created by Musk and his compatriots gobbled up ever greater shares of US gross domestic product, energy output and potable water. The unloved product was shoved into every available online space, cluttering up the digital landscape with junk and hoaxes while promising a far-off profit and a future of easy living.

It’s possible that the discomfort that comes from Grimes’ enshi*tified output is intentional. She’s earned enough grace over several just-ahead-of-the-curve albums for us to believe that the celebratory all-out AI assault of “Artificial Angels” is not earnest.

“I think the AI slop is great. I think culturally, it’s a good thing that it happened, because one of the things that drove people to start really caring about artists again in 2024 was the AI slop. I think everything happens for a reason,” she said in a recent interview with Time. “Most of the album is sort of about me being a bit of a Diogenes about the ills of modernity while still celebrating them.”

With that in mind, the shadow cockroach “Angels” projects into your kitchen may be just a bit of Peter Pan-esque play from an inveterate digital prankster. Still, who wants to feel infested?

Read more

about Grimes