Moments after “The Beast in Me” introduces Nile Jarvis, the real estate scion played by Matthew Rhys, viewers are left with few questions as to whether he murdered his wife.

If you haven’t yet watched the limited series, you may be under the impression that this is a spoiler. Rest assured that it isn’t. Rhys goes out of his way to ensure that his character isn’t the least bit charming. His gaze is colder than a shark’s; his words are spiked with rows of piercing teeth. Nile’s first interaction with his new next-door neighbor, Aggie Wiggs (Claire Danes), reeks of odious self-importance: She comes to his door, angry at having her fury-weighted solitude interrupted by his guard dogs running loose on her property and his estate’s alarm system shattering the neighborhood’s midnight peace.

Greeting Aggie is Nile’s gracious, accommodating second wife, Nina (Brittany Snow), who radiates sweetness as she apologizes and admits that they’re huge fans of Aggie’s work. Then Nile emerges on the upstairs balcony, popping out not to say hello, but to demand why Aggie hasn’t acquiesced to his “offer” to add a paved trail to the communally shared woods behind their homes. He then demands that she report to his home office, where, moments after she steps into the room, he tersely says, “Sit,” as if issuing a command to another canine. Almost as an afterthought, he adds, “Please.”

(Netflix) Brittany Snow as Nina in “The Beast in Me”

What follows is less of a neighborly conversation than Nile prodding a potential victim for exploitable weaknesses. Aggie is a Pulitzer Prize–winning author and profiler of modern icons who hasn’t published much since her bestselling memoir came out in 2018. Nile wonders whether the delay has something to do with her young son’s death four years ago, and not politely. As Aggie explodes at this overreach, you can almost hear Nile’s inner voice exuberantly hiss, “Bingo.”

Of course he killed his wife.

Even as we suspect that, we also accept that Nile’s loathsomeness fails to negate his continued influence in this drama’s version of New York. Decades of lionizing men like Nile Jarvis have made his detestable personality not just easy to spot, but queasily appealing.

The arrival of “The Beast in Me” couldn’t be better timed, with the drama surrounding the release of the Epstein files whirling. Aggie and Nile’s cat-and-mouse contest is compelling, but one part of a larger story about corruption and class-based collusion in a city that is home to more billionaires than anywhere else on the planet.

That also aligns nicely with several modern precepts we’ve come to tolerate about certain New Yorkers who are propped up by political and corporate forces that enable them to get away with just about everything.

Nile may be predatory, but his father, Martin Jarvis (Jonathan Banks), operates with an overt ruthlessness. You get the sense that the ambiguity surrounding whether Nile buried his wife was helped along by Martin, who has the pull and wealth to erase anyone he wants from existence. Martin’s current fixation is muscling New Yorkers out of affordable housing to stomp a permanent boot print onto Manhattan.

Decades of lionizing men like Nile Jarvis have made his detestable personality not just easy to spot, but queasily appealing.

If you believe the world is divided into hunter and prey, and that leadership is most effectively wielded by brutes with twisted appetites, you can see why people clamor to be close to Nile and Martin. Nina, for example, was the personal assistant to Madison (Leila George), Nile’s first wife, who was promoted to life partner shortly after Madison’s apparent suicide. (It’s a story as old as time.) The city’s politicians have almost entirely kowtowed to their pet project, Jarvis Yards, save for one council member, Olivia Benitez (Aleyse Shannon). She has mounted a loud protest movement to skew public sentiment against the project, delaying Jarvis Yards’ construction. But the Jarvises have ways of dragging women like Olivia Benitez through the dirt, too.

Guiding the tension through most of this eight-episode thriller, however, isn’t simply whether Niles will continue skating free of legal consequences for anything he does, but whether he’ll devour Aggie as part of the hunt he’s lured her into — supposedly for redemption.

Officially, “The Beast in Me” isn’t based on any true story, although its resemblance to the events of “The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst” is impossible to ignore. For one, the Jarvises are New York real estate moguls like the Dursts. Like Madison, Durst’s wife, Kathleen, mysteriously disappeared in 1982. Friends and family long suspected he was behind her vanishing, which only increased when others who grew close to Durst began dying violently.

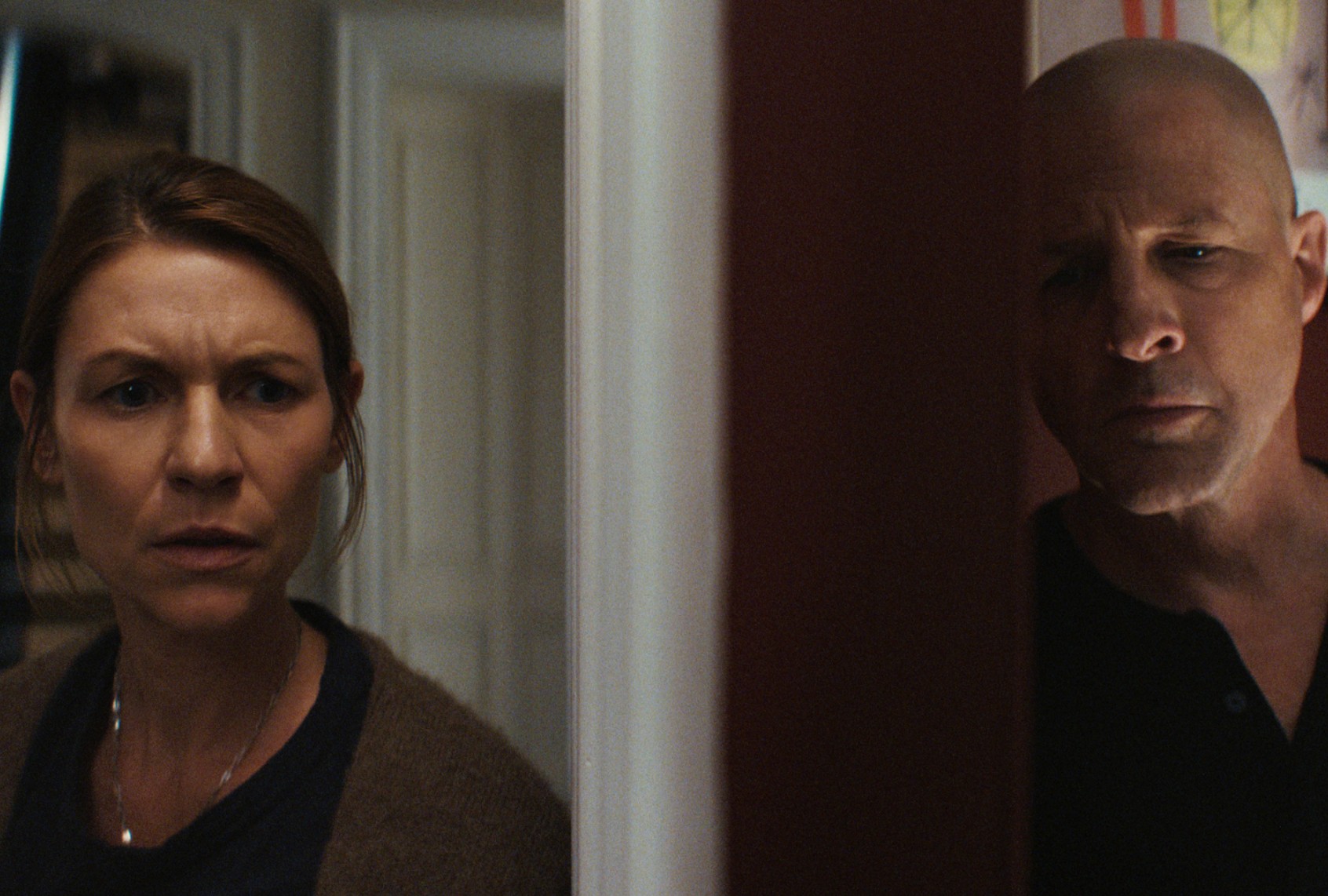

(Netflix) Claire Danes as Aggie Wiggs and Tim Guinee as Rick in “The Beast in Me”

The explosive “Jinx” finale coincided with Durst’s arrest and being charged with the murder of his longtime friend, Susan Berman, in 2000. He was tried and convicted of killing Berman in 2021, the same year that New York authorities charged him, finally, with Kathleen’s death. He died in 2022 before he could face trial.

As for Nile, the Jarvises point to a suicide note that Madison left, one that seemed out of character to at least one person who was close to her, as well as the FBI agent (David Lyons) investigating Nile’s corrupt business deals. Everyone else parrots the official ruling, especially those who have something to gain. The Jarvises’ intimidation tactics secure some of this agreement, enacted by threats and other grim work carried out by Martin’s imposing brother Rick (Tim Guinee), the family’s muscle.

But the audience is only privy to this after Aggie agrees to Nile’s invitation to profile him for her next book, instead of examining the unlikely kinship that existed between Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, people with starkly oppositional interpretations of the law and justice. Potentially fascinating subject matter, no doubt, but also a snooze, Nile tells Aggie. Isn’t he, one of the richest men in America and a guy everyone thinks offed his wife, better bait?

What may be an unusual persona for Rhys to take on is entirely familiar to anyone who has seen that archival video of Jeffrey Epstein in ’80s party monster mode.

From an outsider’s perspective, this is a mutually beneficial arrangement — if the circumstances were equal. Nile recognizes that Aggie’s writer’s block is a byproduct of an all-consuming rancor directed at the young man who caused the crash that killed her son, who walks free after the tragedy was ruled an accident. Aggie also has a stellar reputation in the literary world, making her a worthy instrument to persuade the world of his innocence. Since she’s immune to Nile’s intimidation tactics, he secretly does her another “favor” she’d never ask of him, mainly because doing so also satiates his sociopathic urges.

Danes and Rhys each starred in popular, critically acclaimed prestige dramas — she in “Homeland,” he in “The Americans.” That is the simplest explanation of why “The Beast in Me” has caught on with viewers. “Homeland” co-developer Howard Gordon serves as this show’s showrunner, and he’s amply familiar with Danes’ preternatural ability to break out an anxiety-squinched expression and quivering lower lip precisely when the action calls for them. Few humans pretend to hover on the brink of a total breakdown more convincingly.

Rhys’ portrayal of Nile, though, is another story. As Soviet spy Philip Jennings on “The Americans,” Rhys stood fast in his character’s compassion for others despite his escalating body count. Nile, though, is unencumbered by empathy, guilt, or the urge for compromise, a mile-long bunting of red flags spooled into one cashmere-clad creep.

We need your help to stay independent

What may be an unusual persona for Rhys to take on is entirely familiar to anyone who has seen that archival video of Jeffrey Epstein in ‘80s party monster mode. You know the one, right? Donald Trump whispers something in Epstein’s ear, causing him to break into a ghastly smile. It has been played dozens of times across TV since Epstein became America’s Baba Yaga because that moment, more than others, encapsulates our predatory era.

People from every stripe of the partisan spectrum have clamored for the Epstein files to be made public on the simple assumption that the renowned pedophile had damning relationships with wealthy people they’ve long detested. Trump is only one of them. The thousands of pages of emails, text messages and other communications that the House Oversight Committee obtained from Epstein’s estate provide insight into his links to famous writers, university officials, political advisors, everyone from Steve Bannon to Peter Thiel to Woody Allen.

News outlets have focused on what Epstein’s emails reveal about his friendship with Trump, and what the president knew and did versus Trump’s clumsy disavowals of his old friend. But it shouldn’t escape notice that many of the communications soliciting Epstein’s advice and favors occurred after the financier pleaded guilty in 2008 for soliciting an underage girl for prostitution in Florida. People who knew what he was doing still desired to benefit from his influence.

(Netflix) Jonathan Banks as Martin Jarvis in “The Beast in Me”

Although releasing the files was a campaign pledge, Trump’s political hijacking of the Department of Justice made it a near certainty, he thought, that he could renege on that assurance without losing his base.

After all, the other and more significant promise he made to his followers was that once he returned to office, he would mount a revenge campaign on everyone who had wronged him. “I am your warrior. I am your justice,” he said in 2023. “And for those who have been wronged and betrayed, I am your retribution.”

More than two years after giving that speech, Trump’s retribution campaign has materialized as terrorizing blue cities with Immigration and Customs Enforcement jackboots haphazardly assaulting American citizens and detaining law-abiding immigrants. He’s shaken down the media with flimsy lawsuits that some of the biggest companies elected to settle instead of battling. He’s compelled his Justice Department to indict current and former officials who dared to hold him legally accountable for some of his wrongdoings.

None of it has expanded employment opportunities for Americans or helped the cost of living go down, a factor of reckless tariffs imposed on foreign trade partners — another revenge target.

Want more from culture than just the latest trend? The Swell highlights art made to last.

Sign up here

“The Beast in Me” says nothing directly about any of that, of course, but it doesn’t have to. It functions as a parable confirming our resentment of class abuses, distilling that hostility into a dance for dominance between a hostile prince and a pursuer of truth he suspects he can fool, just like everyone else. Ultimately, it isn’t Aggie’s curiosity about Madison’s murder that spurs her on, well past the borders of dangerous territory. Rather, it’s her realization that Nile set himself on exploiting her darkness for his own benefit.

“Retribution is seductive like that, promising a clean line between good and evil. But it’s an illusion,” she eventually concludes in her book. “I know because I felt its pull after losing my son. I cradled vengeance like a second grief, a sacred companion. I told myself a story about right and wrong, about punishing the guilty.”

(Netflix) Claire Danes as Aggie Wiggs in “The Beast in Me”

Niles caught the scent of her bloodlust, she says at a public reading, “and like some dark angel, made manifest a wish too horrible to name.”

Improbable scenarios are part of this show’s bargain with viewers. I will never understand why people refrain from locking their doors, for example. But the series’ demonstration of what many of us are willing to excuse to rise on the wings of wrongdoing makes absolute sense.

That too many pardon the worst sins of the wealthiest evildoers is the fatal social flaw “The Beast in Me” observes with a piercing stare. Whether this case’s resolution can be characterized as realistic is open to interpretation; as we said, it’s entirely fictional. But the one certainty it hints at is that the Nile Jarvises among us will continue to get away with murder, and worse, because it’s safer to turn a blind eye to those crimes than to insist the perpetrators be held responsible, regardless of how wealthy they are. Sadly, that is the nature of willing prey.

“The Beast in Me” is currently streaming on Netflix.

Read more

about lifestyles of the rich who get away with it