Heather had invited me over to her apartment in Inwood several times in the last year or so, but for one reason or another, the scheduling had never worked out. We kept promising each other, “soon.” Now I was finally here, for the first time, to help pack up her things. She’d been dead for a week.

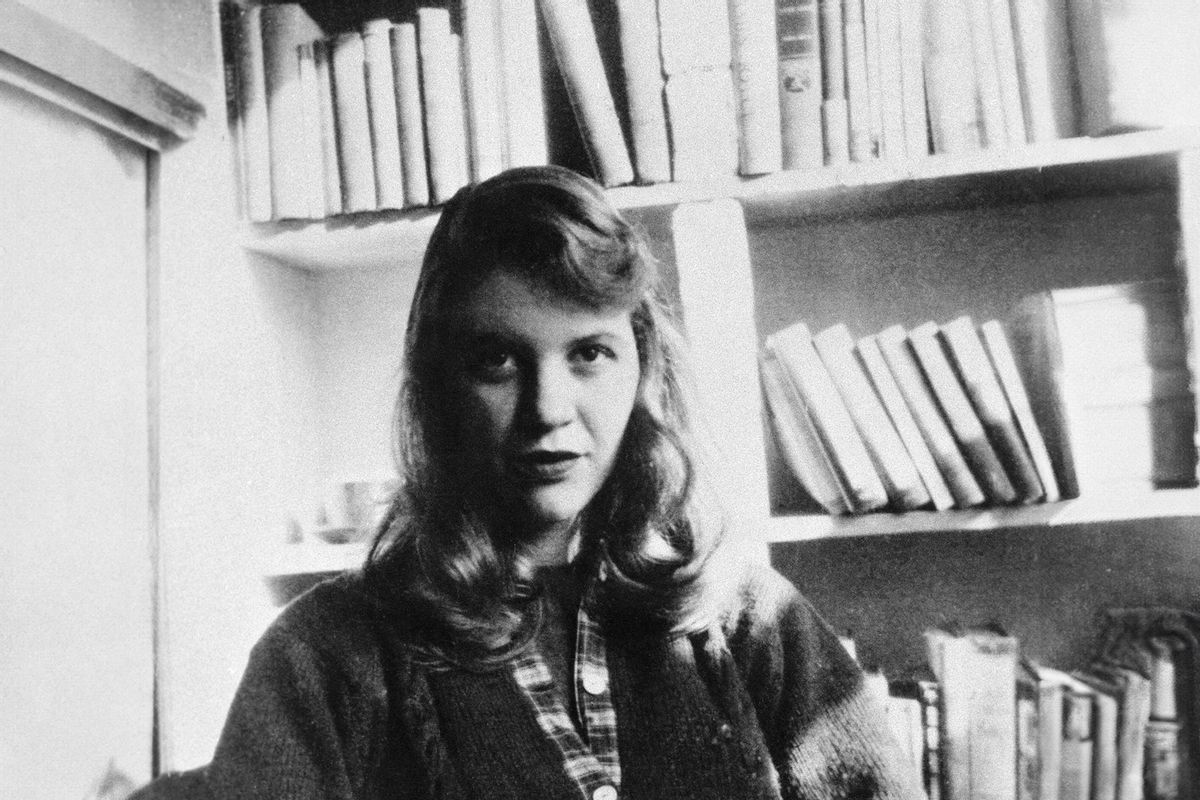

I scanned the stacks of books teetering against one wall, not on shelves but layered like bricks, and a slim off-white spine called to me: Sylvia Plath’s "Ariel." It felt like a morbidly appropriate souvenir of this day.

Heather was a definite Plath Girl as a teenager. I was too — just two of countless teenage girls since the ’60s to proclaim our love for the bracing and violent "Ariel" poems, and "The Bell Jar," Plath’s fictionalized account of her first mental breakdown, suicide attempt and institutionalization — a not-at-all-subtle way of making sure the world knew we were in pain. “I just really identify with Esther Greenwood,” we’d tell adults: a threat. Claiming Plath was a way to elevate our teenage sadness from pedestrian and expected and cliché to literary, tragic, romantic. To tie our early-aughts angst to a dignified and important history.

We weren’t the first or the last teenage girls to romanticize sadness and tragedy, of course. Before Plath there were Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson and the Brontë sisters, each with her own morose devotees.

First Love: Essays On Friendship By Lilly Dancyger (Courtesy of The Dial Press)

First Love: Essays On Friendship By Lilly Dancyger (Courtesy of The Dial Press)

More recently, there was the “sad girl aesthetic” era of Tumblr — young women posting photos of themselves with mascara tears running down their cheeks, or black-and-white selfies in which they’re staring mournfully into the distance, with quotes about depression and existential ennui for captions. The social media sad girl has a very specific tone — the inherent vulnerability of expressing sadness coated in a protective gloss of sardonic humor and irony. Alongside the dramatic crying selfies, sad girl Tumblr pages were full of simple, morose statements like “I hate my life” written in glittery pink cursive or pastels, the cheerful presentation clashing with the message to strike the discordant note central to so much internet humor.

* * *

When I got home from packing up Heather’s apartment, I wrote “Heather’s” on the title page of her copy of “Ariel” in small, neat script, as if I could forget. I started to read it, but only got as far as “Lady Lazarus,” five poems in — to the line about meaning to “last it out and not come back at all” — before the connection to Heather felt too painfully literal. I closed the worn paperback and slid it onto a shelf, where it would sit unopened for years.

Claiming Plath was a way to elevate our teenage sadness from pedestrian and expected and cliché to literary, tragic, romantic.

The tragedy of her death mingling with the brilliance of her poetry made Plath an icon, but it also made her sadness and her tragic end her defining traits. It wasn’t until decades later that a new generation of Plath scholars would advocate for dimension in readings of her work — pushing fans to celebrate her birthday rather than her death date, publishing analyses and close readings of her poems about bees rather than only the ones that evoke death and violence. “The public perception of Plath as a witchy death-goddess had been born and would not soon die,” Plath biographer Heather Clark writes.

I don’t want to flatten Heather in this way — as sure as I am that she would absolutely relish the title “witchy death-goddess.” It’s too easy to remember her as a sad girl because of her sad death. To rewrite her life, starting with the end. But there was so much more to her than that.

She carried herself with the ease of a beautiful woman, swinging her hips and not blushing at raunchy jokes, when the rest of us were still awkward girls.

She was proud of being Jewish and proud of being Chinese and she delighted in the exploration of both sides of her heritage, through study and food and fashion — cooking noodle kugel in a qipao and calling herself a “Lower East Side special.”

She had this guffawing laugh — not the cackle that cracked the air around her when someone else said something funny, but a single goofy exhaled chuckle, the laugh she laughed after she said something she thought was funny. It was so totally incongruous with the hot girl it emanated from, so unexpectedly and endearingly dopey, you couldn’t help but laugh at her laughing at her own joke.

These are the things I most want to remember about Heather.

But the sadness was such a big part of who she was, of how she saw herself and how she moved through the world, it would be as much a disservice to her to gloss over it as it would be to let it take over my memory of her completely.

* * *

The first time Heather called me in the middle of the night saying she wanted to kill herself, I treated it like an emergency.

It’s too easy to remember her as a sad girl because of her sad death. To rewrite her life, starting with the end.

I woke up to my phone buzzing on the table next to my bed, confused. It was past three in the morning. I blinked the sleep from my eyes and cleared my throat before answering urgently, “Hello?”

On the other side of the line, Heather sobbed. When she finally spoke, it was more of a wail, “I wanna die!”

I offered to come to her, asked if she wanted to come to me, asked if I should call an ambulance, but I realized quickly that she didn’t want to be rescued, she just wanted to be heard. She wanted someone to know how much she was hurting. So I listened. I got back into bed and lay down, but didn’t close my eyes.

“I love you,” I said. “I’m so glad you’re alive. I’m so sorry.”

Eventually her sobs slowed to sniffles. I asked if she thought she’d be able to sleep and she sighed, “Yeah.” When I woke up again a few hours later, there was a text from her: “Thanks. Feeling better. Love you. <3”

But that call was just the first of many.

They all played out the same way, but after the third, or fourth, or twentieth time over the next few years, my responses lost some of their urgency. I stopped fearing that her life was truly at stake and came to understand the calls to be a release valve. They became routine. Then they became overwhelming. I started to run out of ways to tell her to go back to therapy, to take her meds; to reassure her that she was loved and yes, she would be missed if she died — desperately. I could sense her wariness, not wanting to give me more of her pain than I could handle. I would never stop taking her calls, but she could tell they were wearing on me, that I didn’t know what else to say.

Eventually, the calls stopped.

I learned after she died that I was one of several people who got these calls — she rotated between us, trying not to dump too much on any one person. But still, one by one, we ’d all burned out. We all reported the same thing to each other, after: “Eventually, she stopped calling.”

* * *

In the year before her death, when she’d run out of people to call in the middle of the night, Heather started venting her sadness on Instagram instead. She posted frequently, mostly memes about mental illness and extreme close-ups of her face, bleary-eyed like she’d been crying. Slack, expressionless. Wearing too much makeup. Her posts made me uncomfortable.

We’d posted all kinds of dark s**t on our LiveJournals back in the day, sure — but Instagram was different, less anonymous. And we were adults now, with professional jobs. I also didn’t yet fully understand what her recent bipolar diagnosis meant; how much was out of her control. I judged her for being such a mess.

Layered over that visceral reaction was a more conscious understanding that I was wrong — that she could post whatever she wanted — and I didn’t like myself for judging her. So rather than staying in the cycle of having a knee-jerk negative reaction each time I scrolled past a new lurid selfie and then feeling guilty for recoiling, I unfollowed her. (This was before Instagram had a “mute” option.)

I know that Heather’s Instagram isn’t a work of art on par with “Ariel.” But it was a hurting woman’s connection to the world; it was how she expressed herself.

Of course, after Heather died, I wanted to go back and scroll through all of those selfies, to examine them like clues, to see if maybe there was a caption that would feel like a message from beyond death, like Plath’s “Dying/ Is an art.” But she’d locked her account, so I couldn’t re-follow after she died. It took seven years for me to swallow my guilt and ask our friend Sydney to take screenshots of some of Heather’s posts and send them to me.

I remembered Heather’s feed as one bleary-eyed, desperate-looking selfie after another, hard to look at and hard to look away from. But in the month before she died, I notice when Sydney sends me a folder full of screenshots, there were only a few of these. I find them beautiful now — not for their tragedy, but just because they’re my friend’s beautiful face. They don’t look as dramatic as I remembered. Interspersed with these selfies is a perfectly normal-looking amalgam of glimpses of her life: a sign for evening services at her synagogue, a spread of new paints, a David Foster Wallace meme, a tattoo she liked of a sloth’s face and the words “Live slow, Die whenever,” and an absolutely stunning black-and-white photograph of her in which her hair is curled and her eyebrows darkened, and she looks like a Wong Kar-wai heroine.

Twelve days before she died, Heather posted a smiling photo of herself with the caption “One week. Different world. Different mood. Different me. Living proof. Things do get better.” I scanned back through her posts and saw that seven days earlier she’d posted two depressed-looking selfies; one of her in bed, her hair covering her eyes, her mouth slack; another of her holding a cigarette, staring blank and expressionless past the camera. But it’s the smiling “Things do get better” post that gets me in the gut. To see that she was trying, that she had hope, even, just 12 days before she decided there would be no hope for her ever again. In this picture, she’s smiling, but her eyes are glassy, with dark circles under them. I can see the strain, the effort it took her to feel optimistic. Or maybe I can only see that now, looking back, knowing she’d be dead less than two weeks later. Would Plath’s reference to carbon monoxide in “A Birthday Present” (“Sweetly, sweetly I breathe in”) feel as ominous if you didn’t know she died exactly that way soon after writing it?

I know that Heather’s Instagram isn’t a work of art on par with “Ariel.” But it was a hurting woman’s connection to the world; it was how she expressed herself. And now it’s an archive rich with posthumous meaning. So I don’t think the comparison is that much of a stretch, actually.

* * *

Heather’s last post ever is a meme, white text against a dark purple background: “i put the hot in psychotic.” A decade later, this meme and the bleak black-and-white selfies are clearly recognizable as pitch-perfect examples of the sad girl aesthetic. Heather didn’t have a Tumblr account, as far as I know, but she embodied the aesthetic on her Instagram right at the time when it started to spill over onto that platform and others beyond its birthplace.

Today, the once-controversial jokes of the online sad girl are ubiquitous far beyond their original little corner of the internet, with people posting casually about depression and dissociation on their otherwise professional Twitter accounts. The Reddit group r/depressionmemes — a mix of the general “lol life is pain” brand of memes you can expect to find on other social media, and posts that directly express, if in meme form, suicidal ideation — has tens of thousands of members. And the sad girl lives on in yet another generation on TikTok, where “#SadTok” videos of (still pretty, young, mostly white) girls looking into the camera as tears roll down their cheeks have millions and millions of views.

If jokes about wanting to die are so casual now, how are we supposed to know when somebody means it?

When Heather and I loudly proclaimed our misery as teenagers, we were signaling our separation from the herd, our rejection of the social standard. Declaring that we saw the world clearly enough to see how f**ked up everything was, even if the powers that be didn’t want us to notice. But these sentiments aren’t subversive anymore — they’re almost assumed as a baseline.

This sense that everyone is depressed feels like it’s at least in part a reaction to the political climate and the literal climate of the last few years; the pervasive feeling that the world is ending, for real this time. Impending fascism, global pandemic, daily mass shootings and frequent catastrophic weather events have primed us all for malaise. And there’s something cathartic about how normal it feels now to say out loud that everything feels hopeless and you’re not sure you’re going to live much longer. But I also can’t help but think of Heather these days when I see one internet acquaintance after another post about being too depressed to cook — not as if this were a dire state to be in, but as a casual way to ask for recommendations of easy recipes; or express their enjoyment of new music by any of the new guard of sad girls like Mitski, Lucy Dacus and Phoebe Bridgers by posting about how hard they’re crying. It all feels so normal that it doesn’t worry me at all. But the fact that it doesn’t worry me sometimes worries me. If jokes about wanting to die are so casual now, how are we supposed to know when somebody means it?

The internet makes it difficult to tell what’s real. This is a common conversation in terms of presenting only our most manicured selves, especially on Instagram — the most aspirational of the mainstream social media platforms. The prevalence of posts about depression feels like a reaction to the too-perfect online aesthetic that developed with rise of influencers. People are rejecting the shiny illusion and trying to show each other that sometimes our hair is dirty and our desks are cluttered and our coffee doesn’t have little foam hearts on it; that sometimes we even want to die. But even when people try to post about the messy, ugly, real stuff, it still feels like a manicured presentation. Like it’s all still curated and put on for consumption, another lever to pull in adjusting how we want to be seen by the world. So much so that even a depression that will soon lead to suicide can feel, through the filter of social media, like content.

Heather wasn’t just sad, she was prone to severe depression. But because being a sad girl had been part of how she presented herself to the world for so long, it seemed like she could go on posting mental illness memes and playing “Crazy” on the jukebox at the bar forever and ultimately she’d be OK.

If you are in crisis, please call the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by dialing 988, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.

Shares