I once lost my job, and at least slightly altered the history of what was then known as “alternative journalism,” because of an obnoxious comment I made in a bar. Human history is full of stuff like that: random encounters that didn’t seem to mean anything at the time, but assume a different resonance in the rear-view mirror.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that story lately, mostly because of its minor-key resemblance to what’s been going on at the Denver Post and the Los Angeles Times, two venerable daily newspapers whose newsrooms have engaged in more or less open rebellion against their corporate owners. But my long-ago personal drama took a much stranger turn toward contemporary relevance this week with the indictments against the proprietors of Backpage.com, a now-shuttered website that has been accused of tolerating, enabling or facilitating the sex trafficking of underage girls and boys.

One could argue that there’s a distant but discernible connection between my entertaining anecdote from 20-odd years ago and that still-murky criminal case. And I’m tempted to suggest that the story that leads from there to here is also the story of what happened to the American independent media, and maybe, along the way, the story of what happened to America. But that part is up to you.

So here’s the scene: Some upper-middle fancy hotel bar in Boston, in the summer of 1994. (I think.) I had just gotten off a plane from the West Coast into a classic Northeast Corridor heat wave, and had almost certainly been drinking en route. I was the editor of SF Weekly at the time, in town to attend the annual conference of the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies, an umbrella group that at the time had dozens of member papers spread across every major metropolitan area in North America, and a whole bunch of minor ones.

(I am happy to report that the organization still exists, as do a fair number of the papers I remember from the ’90s. Many of them have since gravitated online, of course, and I don’t think even its staunchest defenders would claim it has a fraction of the cultural prominence, or the veneer of countercultural coolness, that it did in those days.)

There was an impromptu gathering in the bar of various editors and alt-media characters who knew each other mostly by reputation, or on the phone, or because of the outrageous things we had published. (Remember, it’s 1994. The internet sorta, kinda existed, but I would like those of you over 40 or so to supply that modem-connecting noise.) I started talking to Cynthia Heimel, the feminist legend and humor columnist who pioneered the girl-talk-about-sex genre with a book called, well, “Sex Tips for Girls,” published in 1983. We were soon joined by David Carr, who was then the editor of the Twin Cities Reader in Minnesota but would go on to much greater fame as media columnist for the New York Times.

I liked Cynthia and David very much and they’re both dead now. I hadn’t really thought about that when I started writing this, but I’ll try to steer away from pseudo-Proustian melancholia; neither of them would have any patience with that. Also joining us was a guy named Jack Shafer, then the editor of the Washington City Paper. He’s not dead; he writes a column on the media for Politico these days, and will be back later in the story. Across the table, near Shafer, was a man whose reputation preceded him: Mike Lacey, the founding editor of Phoenix New Times, which had already spawned clone-like papers in several other cities.

I didn’t know Lacey personally, but he was known throughout the alt-weekly biz as a maverick or a “disruptor,” although nobody used that word that way at the time. The New Times papers stood out because they weren’t overtly political and had been successful in fast-growing Sun Belt cities that weren’t especially liberal: Phoenix, Dallas, Denver, Houston, Miami. They did plenty of legit news reporting, to be fair, but they didn’t endorse candidates or crusade for specific causes or line up with particular political factions.

That was extremely different from the journalistic climate in more cosmopolitan and self-important coastal cities like mine, where there were often multiple alt-weeklies competing to out-left each other. Our paper in San Francisco advocated for marriage equality a full decade before that surfaced as a vaguely plausible mainstream political issue. (At a low-end estimate, our readership was about one-third LGBT, and about 95 percent people who saw themselves as LGBT allies.) We crossed a line, apparently, when I agreed to publish the sex-advice column by Seattle writer Dan Savage, who initially wanted correspondents to address him with a hate-speech epithet I’m not supposed to use in Salon. I had to spend an awkward afternoon at the GLAAD offices being benevolently lectured about homophobia; it was like a scene in an imaginary sitcom about San Francisco in the ’90s, except real.

Our principal competitor, the Bay Guardian, campaigned openly for socialism, in the form of “municipalizing” the public utility company and enacting single-payer health care. (I don’t think I knew what that meant at the time.) I’m sure they ran a story at some point about Bernie Sanders, the anomalous congressman from Vermont. I’m sure I laughed about it: Ha ha, some old dude from the ’60s, how tedious. You win some and you lose some.

But let’s get back to that 1994 conference hosted by the Boston Phoenix, a first-generation alt-weekly founded in 1966 that grew into a New England mini-chain, with sister papers in Portland, Maine; Providence, Rhode Island; and Worcester, Massachusetts. It published its last issue in 2013. (The Portland paper still exists, under different ownership, because Maine is not quite part of the 21st century.)

At some point during the drinking, we started talking about the audiences for our respective publications. I said something about how SF Weekly was for unemployed grad students who wore black and never went outside by daylight, and people whose bands were too cool ever to get signed. I was kidding, or at least “kidding”; I believe that’s a literary device known as hyperbole. We had other kinds of readers too: Radical vegans and squatters who believed property was theft and lesbians who worked in libraries and people who spent their college years doing too many drugs and reading too much Jacques Derrida. (See: I can’t stop myself! Even now.)

I know this made a big impression on Mike Lacey because he testified under oath, more than a dozen years later, that he “wanted to kill” me after hearing me say that stuff. A reporter for the Stranger, the Seattle alt-weekly, called me up in 2010 to seek comment on Lacey’s witness-stand description of me as a member of the “snotty upper-class elite” who courted "an increasingly small, sophisticated, cutting-edge audience of underemployed graduate students and disaffected radicals."

I told that reporter that I couldn’t remember saying anything like that. But I'd like to apologize to him now, because when I read the whole thing later in print I thought, well, that sounds an awful lot like something I would say. (Except for “increasingly small,” which was simply not accurate.) What I would say now is that Mike Lacey and I didn’t speak the same language and were virtually incapable of understanding each other, and that when you look around the United States today you see that problem writ large.

Lacey evidently decided to buy SF Weekly as he sat there staring at me across the bar table in Boston, because I was an arrogant asshole (which was fair) and he thought San Francisco deserved an alternative weekly that wasn’t just for black-clad weirdos and vegans and Derrida readers and so forth. That part was what we might call a misreading of the market.

Lacey and his Phoenix business partner Jim Larkin bought SF Weekly from our original publisher (for chump change, basically) early in 1995, launching a period of dramatic expansion and consolidation during which their company became the biggest player — indeed, pretty close to the only player — in the alt-weekly field. Ultimately they would end up owning both the Village Voice and the LA Weekly, by far the most prestigious brands in the industry, along with established weeklies in Cleveland, St. Louis, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Nashville, Seattle and various other places.

Those guys would never again make the mistake they made in San Francisco, where they announced they were buying our paper — and replacing me with the aforementioned Jack Shafer — a full month before they actually closed the deal. So my staff got four issues in which to dramatize our plight and poison the water, depicting ourselves as the scruffy, black-clad radicals being displaced by soulless corporate rube-drones from Arizona, of all places. I could tell you stories about the people in this photograph, taken in a parking lot in what would soon become an unspeakably trendy district: One of them is me, one of them is an editor at the New York Times, one of them edits children’s books at Scholastic, one of them works at a university in Southern California. At least one of them is dead now, but I don’t want to get distracted by that issue again.

Later that year, a homeless man with newspaper in his shoes came up to me on the street and told me it was a shame what had befallen our wonderful publication. All of that was indulgent nonsense, basically: I have no grudge against Mike Lacey for firing me. It was his paper. As for Jack Shafer's brief tenure in San Francisco, of course I'm not an objective observer. Perhaps the fairest thing to say is that he didn't last too long working for Lacey and he did OK for himself later on.

More than a decade later, I went back to San Francisco to testify against Lacey’s SF Weekly in the court case that occasioned the Stranger article mentioned above. It was a complicated suit brought by the Bay Guardian, which Lacey's company had tried to drive out of business in various dubious or illegal ways. New Times and/or Village Voice Media (as it was later called) had to settle that suit for an undisclosed sum well into the millions, several times what it had spent buying our paper in the first place. The entire alt-weekly business was already in a steep downturn by then, so that wasn’t the beginning of the end: It was closer to the end of the end.

Between 2011 and 2013, Lacey and Larkin’s company sold off all the alternative weeklies they had once owned. Some still exist (largely on the internet) and some don’t. Their last remaining property was Backpage, the classified advertising site they had launched in 2004 as an edgier, riskier competitor to Craigslist.

That part isn't incidental at all: If we observe the investigative journalist's dictum to "follow the money," it might be the most important part of the whole story. During the early years of this century, classified advertising -- and more specifically ads for "adult services" or "escort services," meaning prostitution and other forms of sex work -- had gravitated online. To be frank, that pretty much destroyed the business model of the entire alt-weekly industry. Under pressure from law enforcement and government regulators, Craigslist removed its “adult services” category in 2010. Backpage “refused to buckle,” in the words of its Wikipedia page.

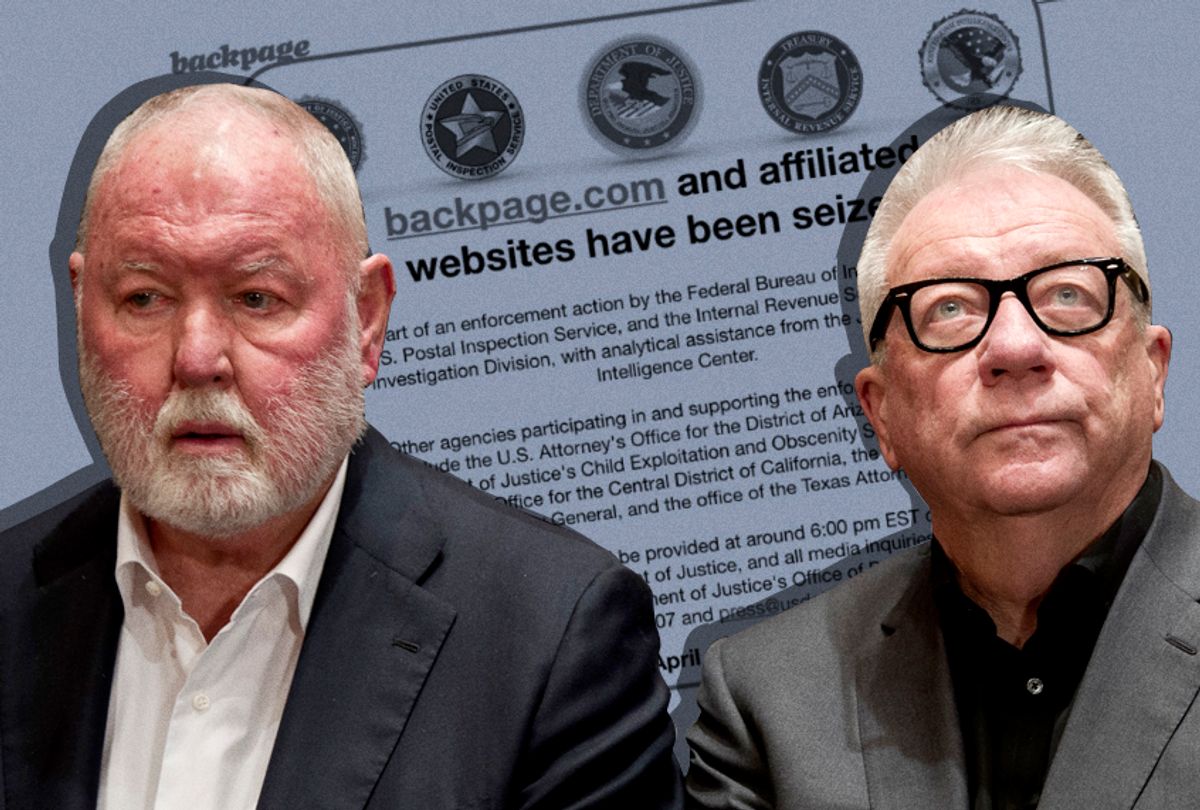

Lacey and Larkin positioned themselves as First Amendment warriors, carrying on the struggle in the commercial realm. That worked brilliantly, for a while. Officially, they sold Backpage to two Dutch holding companies at the end of 2014. But according to the 93-count federal indictment unrolled against them last Monday, that was all a scam. Those companies were allegedly controlled by Carl Ferrer, their hand-picked CEO, and the $600 million purchase price was mostly lent to Ferrer by Lacey, Larkin and two other co-conspirators. Take a look at that number again, and reflect that the guys who had spent $1.3 million in 1995 to buy my little newspaper (barely half of that in actual cash money) made hundreds of millions of dollars in this decade alone off online prostitution ads, some of which allegedly contrived to conceal the sex trafficking of children.

I think I need to make clear that this story is no longer funny and no longer about me. Maybe my interactions with Mike Lacey have taught me to say things more simply. He once hated me so much he tried to destroy my career, but right now he’s sitting in jail in Arizona, the home of his onetime newspaper empire, facing the kinds of criminal charges that are likely to mean the end of someone’s life. (Ferrer has apparently flipped on Lacey and Larkin in grand style, and was reportedly flown around the country last week to enter guilty pleas in various jurisdictions.)

I don’t know the facts of the Backpage case, but everything about it is deeply troubling. On one hand, I don’t believe sex work should be illegal, and I think law-enforcement crackdowns almost always end up making the lives of sex workers worse. What’s more, Lacey and Larkin were longtime adversaries of former Phoenix sheriff Joe Arpaio — the notorious racist recently pardoned by President Trump — who once arrested them on spurious charges that wound up costing the Maricopa County government millions of dollars in damages. It’s not unreasonable to perceive a possible link between that history and these indictments.

On the other hand, if Backpage generated any of its epic flow of money by conspiring with pimps and procurers in various countries to sell underage boys and girls for sex, as is alleged in the federal indictment, then whatever happens to Lacey and Larkin and their co-defendants now is arguably not bad enough. It’s deeply shocking, and I don’t want to believe it.

Here’s what I mean: When I go back to that night in Boston in 1994 with David Carr and Cynthia Heimel, who are no longer available to give us their versions, I want it to be tragicomic. Mike Lacey hated my guts and decided to buy our little left-wing newspaper because we were from different places and different backgrounds and simply couldn’t understand each other, even though we were both Irish-American dudes who worked in the scruffy underside of the news business. I want us to be people of principle, even if he thinks I’m a jerk and I think he’s a dumbass.

I don’t want it to be an awful and tragic story about a guy who started out with more or less honorable intentions (whether or not I approve of them) and launched himself down a path of soullessness, depravity and greed. I definitely don't want it to be a story about how the anti-establishment, truth-to-power tradition of alt-weekly journalism -- which Mike Lacey and I both believed in, in our own ways -- always had a dark side that ended up, in this case, corrupting the entire enterprise. My early career of Mission District burritos and leather jackets and drinking too much was funded by those back-page ads I never really thought about. I hope they all involved consenting adults. But I can't know that for sure.

So when I see Mike Lacey now, pushing 70 and potentially facing a long stretch in federal prison, I feel no impulse to gloat. I feel something else: Not exactly guilt and not exactly complicity, although there might be a tinge of that. I guess it's doubt, because if there's one consistent lesson you learn from journalism and history it's that you should never feel too sure about where to draw the line between the good guys and the bad guys, or about which side of that line you're on.

I suspect there's something in this story about what happened to alternative journalism and Mike Lacey's newspaper empire and the civic and cultural life of America's cities that speaks to bigger questions. (Such as the always-relevant David Byrne question: How did we get here?) Maybe it offers an illustration of capitalism's general tendency to default to its darkest impulses, or the way our country has torn itself apart into warring camps with competing visions of reality. But I played a role in this story, however minor, so I'd better not kid myself that I'll ever understand it.

Shares