However you feel about President Donald Trump and his policies, “Trumpism” ought to signify a specific political philosophy — the form of populism that Trump has brought into the mainstream of American politics, which had either not been there at all in previous eras or had only lurked in the background of our national conversation.

To better understand Trumpism, I have tried to perform the difficult exercise of approaching it from a detached point of view. (I am pretty much a New Deal liberal myself.) If Trumpism is indeed to be distinguished from other forms of conservatism and populism — and if liberals are to recognize those distinctions — it becomes necessary to look at how Trumpism deviates from status quo conservatism. It also becomes necessary to perceive advocates of Trumpism in the same way that they see themselves.

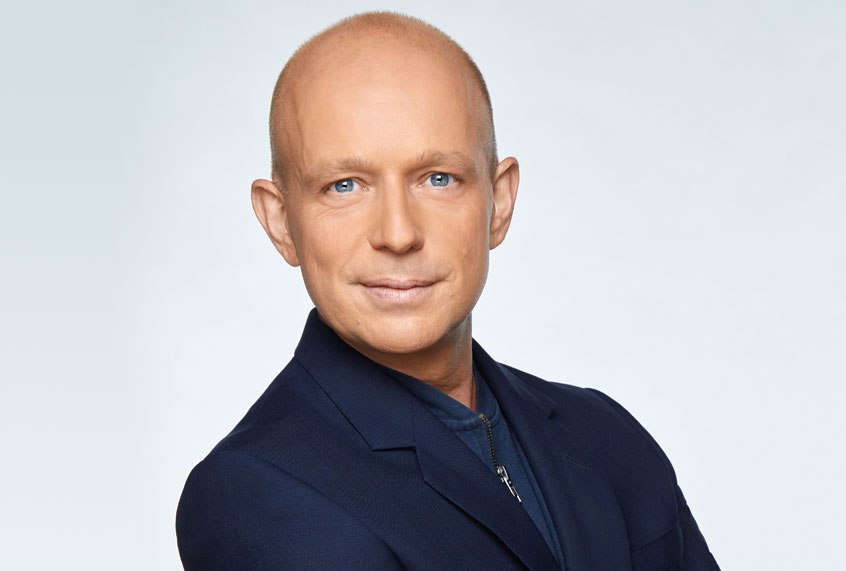

It was for this reason that I reached out to Steve Hilton, a man of many ideas and a policy aficionado who previously worked in British politics, including as an adviser to former Prime Minister David Cameron. Tuesday marks the two-year anniversary of his Fox News program “The Next Revolution with Steve Hilton,” a weekly show that airs on Sundays at 9 p.m. Eastern.

Donald Trump has made it abundantly clear that he watches Hilton’s show. In the past five weeks Trump’s Twitter account has either cited or directly quoted “The Next Revolution” on six occasions. When Trump was interviewed by Hilton on May 19, the show averaged more than 1.3 million in total viewers, which was higher than CNN and MSNBC combined in that time slot, according to Nielsen Media Research. And Hilton’s program has itself done well in the ratings, outpacing CNN and MSNBC in total viewers for its time slot so far in 2019.

Hilton also wrote a book last year, “Positive Populism: Revolutionary Ideas to Rebuild Economic Security, Family, and Community in America” that sheds light on the distinct brand of conservative populism that Trump’s followers find so attractive. I have no idea whether Trump has read “Positive Populism” or agrees with Hilton’s policy prescriptions, but the premise behind Hilton’s book — namely, that movements like the one that elected Trump are rooted in people being fed up with those they perceive as out-of-touch elites — rings as very, well, Trumpist.

Hilton has a knack for presenting his ideas in a lucid and intelligent fashion, and for being respectful to others while holding firm about his own convictions. That makes him worth listening to, for anyone who genuinely wants to understand conservative populism. I asked him to explain how Trumpism can be distinguished from other populist and conservative philosophies that came before it. What are its basic ideas?

“I think the closest articulation of it actually is that ‘America First’ phrase,” Hilton said. “If you look back, the interesting thing about him is that these are very consistent views. I mean the other night on my show, I did a sort of China thing, where we had clips of him in the 1980s and ’90s, [and in] 2010, saying exactly the same thing about trade as he is saying today. And people say, ‘Oh, well, he was then talking about Japan.’ He was, but he was also talking more recently about China, and China’s rise, and so on. Totally consistent for the past 30 years or so.

“In those days it was all about America: ‘We are being ripped off, America should be doing better.’ It’s a fierce kind of patriotism, and a belief in America, I think. ‘America First,’ therefore, is the closest thing I think you’re going to get to a defining idea of Trumpism. And that does connect trade issues and immigration issues.”

If it sounds like philosophy isn’t really a big thing for Donald Trump — well, Hilton would agree. “I think the president himself would be the first to say that the notion of a sort of philosophical approach is somewhat alien for him. That’s not how he sees things. He really is, I think at heart, a pragmatist. He’s like, ‘OK, there’s a problem here. How do I fix it?'”

Hilton elaborated on where his own views dovetail with Trump’s: “I think that the skepticism [about] unaccountable policy-making, particularly in the international arena, I think there’s a really strong overlap there.”

Hilton specifically cited Trump’s views on trade policy, which he said was “likely to be one of the defining elements of the Trump presidency,” which is almost certainly true. He added that he shares Trump’s distrust of “multilateral bodies that end up being run by international bureaucracies,” including the World Trade Organization and European Union.

Those are especially significant aspects of Trumpism because they involve breaks from the political status quo. Since the 1930s, presidents and presidential candidates from both parties have supported “free trade,” as the term is used today, in large part because the protectionist policies of Herbert Hoover were widely believed to have worsened the Great Depression. (Whether or not that’s true is a matter of ongoing debate.)

Similarly, major-party nominees since the 1940s have united around the idea of U.S. participation in multinational organizations such as NATO in order to preserve an international order. In the aftermath of World War II nearly everyone in American politics accepted that we could not afford to stay out of those organizations if we wished to protect democracy, thwart tyranny and prevent World War III.

By bucking the status quo on these issues, Trump has broken with political norms that have existed since Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, which were implemented in direct response to the national traumas of unprecedented economic hardship and war. In the process, Roosevelt himself gave ideological definition to the modern Democratic Party and oversaw America’s transformation into an economic and military superpower.

Trump isn’t quite the first president to break from the post-FDR status quo. The emphasis on decentralized government and the increased influence of Christian conservatism in the Republican Party, for example, can be traced back to the rise of the New Right in the 1960s, which culminated in Ronald Reagan’s presidency. While Trump seems to identify more with Andrew Jackson than Reagan — which is at least somewhat ironic, since Jackson was the first Democratic president — the Trump White House’s deregulatory, anti-tax and socially conservative policies are direct continuations of the Reagan Revolution.

Yet Trump has clearly accelerated the deviation from a policy continuity that had endured for more than 70 years. During his interview with Salon, Hilton connected foreign policy and trade policy to immigration, a third area where Trump’s policies have broken decades of established policy norms followed by both Democratic and Republican presidents.

“This immigration plan that he just put out is very true to his instincts,” Hilton said. “He’s not a restrictionist. He’s not. He talks about it the whole time as a badge of pride. Because our economy is now doing really well, we need more people. They’ve just got to be skilled people. So it’s all about America being No. 1, booming — more people, more investments. To me that is the core Trump thing, ‘America First,’ delivered through economic means.”

Hilton added that this concept also informs Trump’s view on military interventionism. He described Trump as opposed to “global militarism and international expansion, because it drains the economy more than anything else. It’s like, why would we waste trillions of dollars in the Middle East? That doesn’t help our economy. I think that’s how he sees things.”

I made clear to Hilton that I don’t share Trump’s views on any of these issues, or his either. How can liberals, I asked Hilton, engage in a productive conversation — to use Hilton’s own term, a “positive” one — with Trump and Trumpists about these disagreements?

Hilton cited the occasion last week when Trump cut off a meeting with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, irate about the Russia investigation. Trump is willing to talk about policy with anyone, Hilton argued, if he feels his legitimacy isn’t being questioned.

“He and his supporters will say, well, hang on a second — and, by the way, I would agree with this — you can’t expect him to be all cooperative when five minutes before the meeting, you do a press conference basically accusing him of running a Watergate-style cover-up like Nixon. That’s not realistic. You’re questioning the legitimacy of his whole administration. Of course he’s not going to sit down and talk to you after that.”

Hilton agreed, however, with my premise that Trump should be willing to talk to journalists who may disagree with him on matters of substance. “I think if you keep it to policies and ideas — a respectful ideas-based conversation, and not, ‘Why are you a Russian traitor’ or whatever, you’d have a very, very good conversation,” Hilton suggested. “I definitely think that people would see a side of the president that they can’t imagine, if all they see are the angry tweets about the Mueller witch hunt and so on.”

What can liberals learn from Trumpism? Perhaps the first lesson is that any viable political movement in this era must position itself as siding with ordinary people and not with “elites.” This is a skill that Trump possesses in spades, as do some progressives at the opposite end of the spectrum, like Bernie Sanders or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

While ideology isn’t irrelevant to populism, the latter is more a matter of style than of policy. People who gravitate toward Trump believe he is fighting for ordinary people against various elite groups. Any politician who wishes to build a legacy in this portion of the 21st century — who wants not only to gain power, but to hold it and do something lasting with it — must, in that sense, be a populist.

Liberals and progressives also need to learn to talk to people like Steve Hilton, even when we strongly disagree with them. That process isn’t always easy, but it does no good to demonize one’s opponents or to misunderstand their arguments. Democracy depends on dialogue, even when it’s difficult. As I’ve learned from talking to conservatives over the past year or so —from Tucker Carlson to Trish Regan to Raheem Kassam of Breitbart — it can be done.