A week ago last Saturday, my mother called me just as my kids and I were ordering food at a diner in Massachusetts, partway through a long day’s drive. There’s nothing exceptional about that, and moms the world over have an uncanny ability to phone their adult offspring at inconvenient moments. But my mother is well over 90, and while she doesn’t have any major cognitive impairment, she has pretty much stopped making phone calls, to me or anybody else.

So I took the call, and my mother was nearly crying — with happiness. She had been watching the results of the Nevada caucuses on TV, and she was calling to tell me how happy she was that she had stuck around long enough to root for a socialist presidential candidate who might actually win. “He’s 80 and I’m 90,” she said — which isn’t quite right at either end, but close enough — “but it was worth waiting for.”

I could have told her, I suppose, that whether or not Bernie Sanders really qualifies as a socialist is debatable, and that even after the sweeping victory in Nevada, it remained unclear whether he could win the Democratic nomination, still less the presidency. (She didn’t enjoy the South Carolina result this past Saturday nearly as much.) But I didn’t say any of that, largely because I love my mom and it was immensely moving to get that unusual phone call while we were sitting there in Lowell waiting for our orders of ribs and pot pie to reach the table.

I also didn’t say it because she was right, in a way: One important element of the narrative about this political moment is that “movement politics,” in the leftist sense, has become a central factor in the Democratic primaries for the first time since the Rev. Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition campaigns of 1984 and 1988. (Jackson himself has drawn the comparison several times, including very recently.)

I was there for those too, and sitting in that diner in Lowell dealing with the upwelling of emotion and memory from across the decades — both my own actual memories and my family history — was one of those extraordinary experiences where you feel the connectedness of human existence, which we too often experience as fragmented and isolated. My mother was a labor activist and a member of the Communist Party in the 1940s, organizing office workers in Washington and mine workers’ wives in western Maryland, and then was a Henry Wallace delegate at the Progressive Party convention in 1948. (Come at me, red-baiters; I’ve heard it all before.)

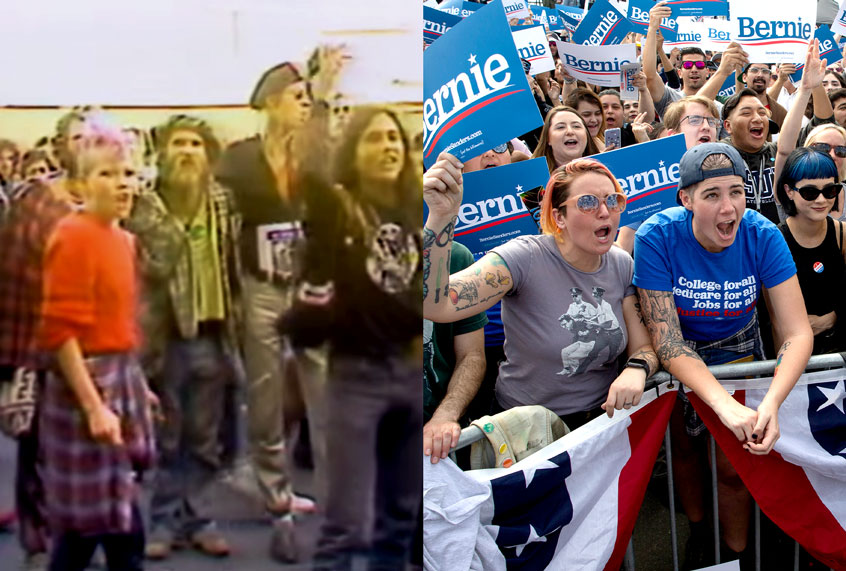

As a college student in 1984, I was outside Moscone Center in San Francisco when Jesse Jackson was the only prominent Democrat willing to come out and engage with what the media called the “peace punk” protests during that year’s Democratic convention. Some people involved called it the “Summer of Hate,” in an explicit rejection of the hippie ethos of 1968 — but trying to make that distinction comprehensible to younger generations is a lost cause.

Most mainstream Democrats were profoundly bewildered, if not outraged, by the sight of angry young people protesting their convention rather than making common cause against Ronald Reagan. In retrospect, especially given the present-day vitriol between the Sanders campaign and the rest of the party, I understand that better than I did at the time. The mayor of San Francisco, future U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein, repeatedly sent in the cops to break up protests and restore some semblance of order, which they did, shall we say, with vigor and enthusiasm.

Gary Hart and Walter Mondale, who were still struggling over a nomination that hadn’t entirely been decided — yes, superdelegates were involved! — completely ignored what was going on outside the arena. Jackson, who hoped to use his 400-odd delegates as a bargaining chip for progressive policies, came out to see us during one especially rowdy afternoon. He had completely lost his voice but stood on a riser croaking into a bullhorn, telling us that he understood our concerns and would represent them inside the convention as much as he could.

What were those issues? I won’t pretend they were entirely coherent or consistent, but the punks and anarchists who gathered in San Francisco that July believed the Democratic Party of that era would do little or nothing to address systemic racism, police violence, the AIDS crisis or (most of all) the threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union, which hovered over everyday life in America like an ever-darkening cloud.

My friends and I might have told you at the time that the Democrats were not seriously opposed to the vicious rightward turn in American politics represented by Reagan’s victory in 1980: They wanted to modulate it somewhat and frame it in friendlier terms by putting a few women and black people on the stage, but both parties were just different faces of the same failed and corrupt system.

Be as judgey and as “vote blue no matter who” as you like; my point here isn’t to defend that analysis. Here’s how I see it: There are clear historical threads that lead from that moment to this one, 36 years later, and yet everything has changed. Some aspects of the Democratic Party’s current dilemma are almost eerily familiar from that time, but the context, the issues and the cast of characters are almost entirely different. (Was Bernie Sanders personally at that convention? That seems entirely likely, but I haven’t been able to figure that out.)

If the original Sanders campaign of 2016 was unquestionably the grandchild of that ’80s and ’90s protest tradition — a “movement” insurgency that came much closer to winning than anyone expected — the 2020 Sanders campaign is something else again. On the cusp of Super Tuesday, this controversial and still-improbable candidate is poised for a historic breakthrough, no matter what happens.

Let me be clear that I’m observing a personal dictum, drawn from advice I got years ago from Bill Moyers: Who will win and who should win are always the least interesting part of politics. I don’t make specific predictions, and I don’t try to convince readers how to vote. (The first is always likely to be wrong, and the second is none of my business — and both of them are likely to drive away everyone who doesn’t agree.)

I don’t know how many states Sanders will win this week, although it will definitely be a nonzero number, and will include some big prizes that would have seemed unlikely just a few weeks ago. I don’t know whether Sanders will emerge on Wednesday as a dominant frontrunner or locked in a death-match with Joe Biden that could extend until July. With the abrupt departures of Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar within the last 48 hours, and the Democratic wagon-circling around Biden in full effect, that latter scenario has gotten a lot more plausible.

I have some misgivings about Bernie Sanders both as a potential Democratic nominee and a potential president, most of them for predictable and obvious reasons. I have no investment in lecturing people who dislike Sanders either for ideological reasons or his admittedly abrasive personal style, and entirely too many people who largely agree with him on the issues have been driven off by the abusive behavior of some of his online followers.

But the Sanders campaign of 2020 is an extraordinary thing — a predominantly young, predominantly working-class leftist coalition of people of many races, backgrounds and faith traditions. No matter what you may have been conditioned to believe, it is not a predominantly white campaign or a predominantly male campaign, and it is absolutely not a predominantly middle-class campaign. Many observers have struggled to articulate how and why Sanders’ campaign — which was written off so early by so many people — has survived and prospered, while Elizabeth Warren’s superficially similar campaign has fizzled.

I do not dispute that sexism in the media and the voting public has played a role in the peculiar tale of Warren’s rise and fall, but there is a simpler and more powerful explanation. Warren surrounded herself with “movement” progressives, and has learned to talk the talk convincingly. But she is not a movement person. She is a lawyer, an administrator and a policy wonk. Her tactics and goals are reformist and managerial, not transformational or revolutionary. Her fans will tell you that would make her a better president than Bernie Sanders, and they may be right. We are not likely to find out.

This will come as cold comfort to Bernie Sanders’ fans if he is defeated again this year, but as historian Michael Kazin recently observed in a New York Times op-ed, his campaign has already transformed the Democratic Party and American politics, win or lose. Kazin compares Sanders to William Jennings Bryan, George McGovern and, yes, Jesse Jackson, all of whom “stirred great enthusiasm among voters but also met stiff resistance within their parties, a major reason none came close to taking the White House.” They also all shifted the center of political gravity and created new possibilities, which in some cases took many decades to arrive.

This sense of historical possibility, and of history echoing itself in strange and unpredictable ways, is exactly what my mother and I channeled during that phone call. Sanders wants to be the next Franklin D. Roosevelt, as Kazin sees it, but it’s just as likely he will become the next Bryan or Jackson, a “transformative figure” who changes the world even in defeat. Whatever happens on Super Tuesday or at the Democratic convention in Milwaukee or on Election Day in November, Bernie Sanders will be remembered as the symbol of an important pivot-point in 21st-century political history. Is there anyone — I mean, literally anyone — who believes that Joe Biden will be more than a footnote?