Detroit native Selina Mahmood was in the first year of her neurology residency when the pandemic hit. Abruptly, she was thrust into a healthcare crisis of urgent need and conflicting guidance, a period of intense demands — and profound loneliness.

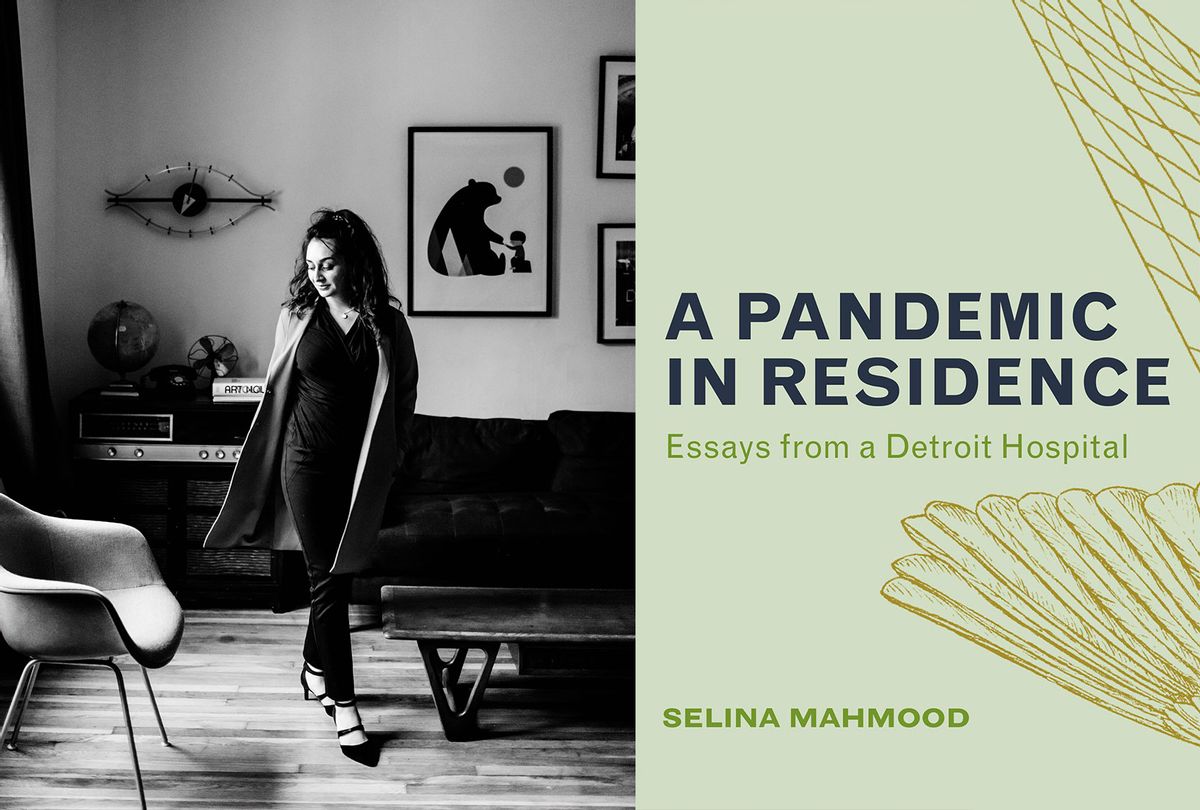

Now, those early days of COVID-19 and a previous presidential administration feel like another era in history. The threat is not obliterated and the pain and grief have not dissipated, but that initial confusion and exhaustion have transformed. And Mahmood's "A Pandemic in Residence: Essays from a Detroit Hospital" is a profound, moving and unfiltered account of not just a frontline worker's experience at an unprecedented moment, but a story of family and identity, of pop songs and PPE.

Mahmood spoke to Salon via phone recently, after getting off from a night shift, about her pandemic year, and what it taught her about our healthcare system. As always, this interview has been condensed and edited for print.

The book takes us through December of 2020. What do your days look like now compared to what they were a year ago?

At this point last year, I was still living in the hotel. I was thinking back about it yesterday, like, "I can't believe I lived in a hotel." It's kind of surreal. It was not nice. It was super lonely and very strange. It already feels so long ago.

I've become much more comfortable in being a doctor, I was a junior when I wrote that book. I'm senior right now and there's a junior under me, so the roles have reversed and I'm overseeing things. Just last night I had a patient who coded on the floor. She had acute respiratory distress. It's crazy comparing myself to my first year versus what it's like now. We called the code blue; we called in anesthesiologists to intubate the patient. Something I realized, because I had a junior under me, is I this isn't about being smart. When you do the same thing and experience it enough again and again, it's crazy how much you actually end up learning.

What was your experience, as a doctor in training, when this started?

It felt very catastrophic, and things were things flipped upside down. I remember thinking, "Oh my God, I cannot believe that this is happening." When we initially started hearing about the COVID cases rising, it was like, "It's happening. It's happening." I remember when the day that the surgeon general recommended stopping all elective surgeries. I've never had that happen, ever. Then the economy dropped and then everything in the hospital changed. It emptied out. At the same time, there was the sense of urgency, just wearing masks everywhere and not being able to see people's faces anymore.

A lot of people I was looking forward to working with, I didn't get to work with because everything shifted. And then, it's so strange that it's still going on. I thought it almost felt like either the world will end or will go back to normal. Being at this end is strange, because this is just normal existence now.

As you write very early on in the book, being where you are in America, there was not the sort of unified response that we had here in New York City. You talk about hospitals having very different procedures and the frustration of that as well.

The hospital down the next county was dealing with things differently. You expect it to be science, right? Science is supposed to be fact. That there was so much fiction in what should have been scientific. To me, that's super frustrating.

I'm curious how you wrote this book. At what point did this move from being something you were writing to anchor yourself in this time to feeling that this was actually a body of work?

It started formulating into a body of work while I was living in the hotel. I was super isolated. There were no other humans except for literally the bellboy. You already feel super disorientated, the anxiety goes up. I didn't know what to do, so I just started putting it together. Obviously, I didn't finish the writing while I was there, but that was the initial point where it started coming together.

But I started writing even before I moved into the hotel that first week, just because it felt so monumental. That Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, I actually started writing right off the bat. It just started off as notes in my cell phone, just for something for me to remember myself. I would actually write in the hospital while walking to a bathroom break, or getting lunch. I would write things in the moment sometimes if I felt them.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

It's hard doing that in real time, because when you're writing about events as they are happening, you don't have that distance from them.

There's this Lit Hub article on writing about an event as it occurs, and how that can either be a huge failure or work out. If you get a feeling intuition of what's going on and things unfold differently, your work kind of collapses. When I was writing about Trump, even though I kept thinking, "I don't think he's going to win and he feels like the past," I knew I was going to have to edit that out if he ends up winning.

You also write a lot about you family and about your relationship to them, about race. What are the boundaries around that? It's so different from the other parts of the book.

I ran through a lot of the stuff that I wrote about my family to them, to make sure they would be okay with it. You don't necessarily know what's going to offend other people or not sometimes. I actually didn't end up editing any of it out, because I have written other stuff in the past and I think my parents and my sisters are used to me writing.

What was the hardest part to write about? Were there parts of this where you thought, "I'm not sure how to tell this story" because you're so deep in it?

For some of the parts, it was starting off and admitting that you're not perfect in the beginning, and that you make mistakes and medicine is super hard.

Doctors aren't encouraged to do that.

Especially because the repercussions are so high. But that's how we learn. That's why we're in training in the first place.

When I started off, I was much more emotionally invested in patients, and that's something that we're not encouraged to do either really. You're told to distance yourself from patients all through med school as well. I did not start off with that emotional distance at all. That's something I've had to work on significantly. I realize how much I have managed to distance myself when I see new interns who are that emotionally invested.

It's such an ethical conundrum for physicians, because you have to figure out your sweet spot of emotional distance and having an emotional investment.

Sometimes I'm glad it's this way rather than it being the other way, that I came in over invested and had to move away rather than having come in super distanced and having to make my way in. I feel like it's harder to do it the other way around.

You've seen so much up close now and experienced so much in a way that goes above and beyond the already incredible rigors of being a resident. How do you think that's going to inform you as a doctor?

First of all, I don't even know when things are going to go back to normal anymore. Is this still going to be the world I start my practice in or become a staff? That uncertainty is very much up in the air.

The public health issue of everything has become much more in the forefront of things. I don't know if it's just the normal intern experience or because it's been heightened by COVID, but all the problems with lack of community, lack of insurance, they're just so in your face. There's a bigger problem than my patient coming in with a migraine. There's a whole social structure behind this patient, which isn't working. And that's a huge problem.

Shares