In the first few weeks after Donald Trump got elected, George Orwell — an author who died in 1950, when Trump was still a child — saw his books rocket to the top of bestseller lists. The gaslighting of an authoritarian figure like Trump renewed the public's interests in Orwell's writings, especially his novel "1984," as a spotlight into the tactics that fascists and other far-right figures use to crush the human spirit.

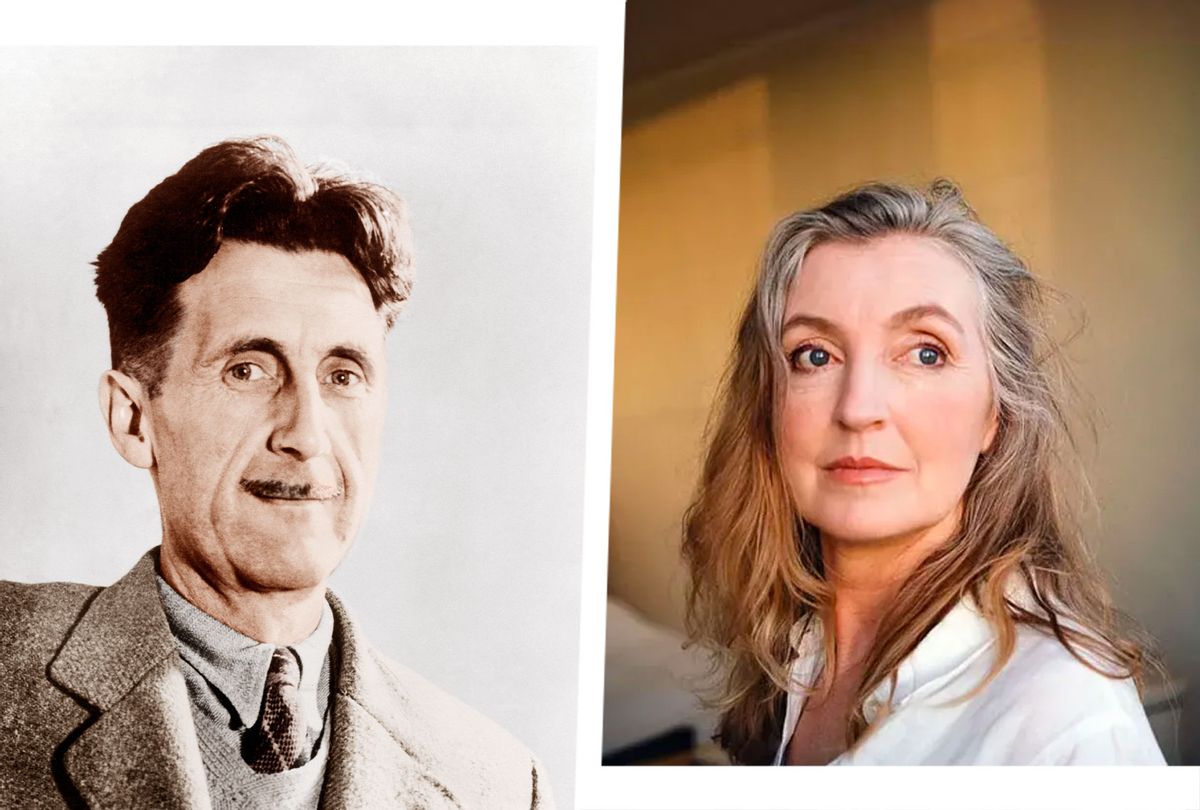

Unfortunately, this revisiting also ended up reinforcing the standard view of Orwell as a stern socialist, too busy fighting the forces of totalitarianism to enjoy the finer things in life. It's this view that author Rebecca Solnit pushes back against in "Orwell's Roses," her unconventional new biography of the author of "1984" and "Animal Farm." Solnit uses Orwell's lifelong love of gardening to ask deeper questions about the value of pleasure in our politics, the human relationship to the natural world, and what the modern left could learn from Orwell and his love of roses.

Solnit spoke with me on "Salon Talks" about her book and why it's good for humans, as they say on the internet, to touch grass once in awhile. Or, as Orwell did, to plant roses. Read or watch my conversation below.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Rebecca, I want to start with talking about George Orwell who is a person who has had a surge of interest after the election of Trump. I think readers have been buying up his book, "1984," in huge numbers. Why do you think it is that he's the author that so many people have turned to in our troubled times?

He, more than anyone, nailed what it looks like to live in a world of national gaslighting, of propaganda, of how much authoritarianism is not just authoritarianism over the economy, the law, human rights, but over consciousness, culture, language, representation. And so he became very relevant when a would be authoritarian who is also a compulsive liar, suddenly takes power in an illegitimate election.

RELATED: "I'm not getting over violence against women": Rebecca Solnit discusses her new anti-memoir

Is that why you were drawn to writing about him during this time, or was it something else?

No, Orwell's been important to me since I was really young. He's one of the handful of non-fiction writers who really kind of gave me a template for what I wanted to do as a writer before I knew what it was and what the words for it were. And I'd gone to him in a lot of other eras. He was certainly very relevant in the early 2000s, in the Bush era, when we even had a website called The Memory Hole for all the lies and facts being kind of slung around in the name of the global war on terror and Bush's hegemonic moment. And he'd been a huge influence on me as a writer as well.

No, it really was, as I recount in the book, that I was on an errand looking for the fruit trees Orwell planted for my dear friend, Sam Green, and found that they had been cut down, but that the roses he planted allegedly were still growing. And it just raised the question for me, "What did this great prophet of totalitarianism, this person renowned for facing unpleasant facts, what the hell was he doing planting roses?" It felt like it allowed me to think about a lot of things beyond Orwell himself, about pleasure, meaning, joy, as they relate to politics, aesthetics versus ethics, those things we need to do that may look trivial, or bourgeois, luxurious that might be essential to doing the really important work we're here to do.

And in a lot of related questions . . . And it was also in Orwell who was deeply engaged with the natural world, which in a time when the natural world was the site of our central climate crisis, made him seem relevant in a different way, and also made him seem like a really different writer than I'd been told. I think everyone has this impression of Orwell as this very grim, stern, pessimistic, austere guy, and to just find out how much he enjoyed himself, how passionately he gardened, how much pleasure he took in his chickens and goats and roses and crops, and grazing those goats on the public common, really gave me a different Orwell than the one I always been told was who he was. And that led me to look at his writing again. The writing had shown that all along, but we hadn't seen it.

As you say, there's this of image of Orwell as this austere socialist, and obviously in "1984," which is his most famous book, it really focuses on Big Brother. Most of the discourse focuses on the Big Brother aspects of his writing, and coinage of terms like double speak and double think, his insights into the constant surveillance. But as you write, "Orwell did believe devoutly in moments of delight and that he included this fascination in '1984'." So tell me more about that and why you think this kind of interest and delight, which the roses represent, it was so crucial to making that book a classic.

I don't think it – I think it went kind of undetected. And I've read "1984" many times, starting with when I was a teenager. I had read it not that long ago in the Bush era and focused on other things. In light of what I learned from Orwell's letters and diaries and the essays, including the one that prompted me to visit the cottage where he planted the roses and the food trees, found traces of this other Orwell who actually enjoyed himself immensely, the kind of "gather ye rosebuds while ye may," carpe diem sensibility.

And so when I went back to read "1984," it felt like a new book, because how does Winston Smith rebel against the regime of big brother? And he does want to topple the regime. He doesn't have a lot of capacity to do it, though he does try to join what he hopes will be the rebellion, but he breaks all the rules. He has a passionate love affair. He wanders off by himself in places he's not supposed to go. He does things, hiding from the omnipresent surveillance of Big Brother. He cultivates memory, emotion, a sense of history, an attempt to establish facts independently.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

So as to create – there's a wonderful line I quote by Hannah Arendt that the ideal subject of totalitarianism is someone for whom the difference between truth and falsehood no longer matters, and I'm paraphrasing roughly. And so someone for whom it does matter a great deal, which is what we should all strive to be and what I think we as nonfiction writers, you and I, try to help people be, is to make a self that can resist, a self that can think independently, a self that's not so manipulable. And so we see Winston doing that. And that's one of the things that's really striking, is that the world of sensory perception is a kind of immediate, empirical reality that can counter the reality of propaganda and lies.

So it actually matters, as well as potentially gives a huge amount of pleasure, and you see that in the book. But what struck me is that the very first thing that happens is Winston Smith pulls out this beautiful book with luscious creamy paper. He bought it at a junk shop in the proletarian district, a junk shop that will become very important, and he starts writing on it. And the sheer pleasure of the texture of the paper, the act of writing, the ink, the subject of introspective, independent thought are all really important. And so this tiny act is essential and a pleasurable act, as well as an act of rebellious, independent, introspective thought. And that's really where the book begins and it's off and running from there, and it describes the golden country that he's dreamed of. And then in a way that reminds us this is not a realist novel, he comes to a real golden country that exactly matches up the ones that he's dreamed of and a woman who actually does this great free central gesture of pulling her clothes off that he's also dreamed of.

And we realized that beauty and nature, and sex and pleasure, and bodily life, and love are all acts of resistance in a sense. And that all brings us to what I think is the climax of the book, the third time Winston looks out the window of that junk shop, where he's renting the bedroom above the shop to continue the love affair, and he sees this stout middle-age proletarian woman singing in a beautiful voice, hanging out diapers. And here comes someone up the stairs, this might be the landlord, but I'll continue for a moment. And I love that moment. First of all, Winston has the sudden realization that the woman is beautiful, and it feels like Orwell himself is seeing women in a way that he and most straight men who write novels usually don't.

Secondly, the whole thing that drives it is a rose metaphor. He thinks why should the rose hip be less beautiful than the rose? And I love it. In the very heart of "1984,",you find a rose metaphor, which is something which reminds me of something I've been harping on for years and in many books, which is that the natural world, the organic world, the animal world, the vegetable world, the spatial world gives us our metaphors, which is how we understand the world, how we relate things by analogy. And so it's this remarkable moment, and Winston has thought over and over, if there's hope, it lies with the proles. A very standard interpretation of "1984" is that because Winston himself is captured, tortured, brainwashed, destroyed psychically, then there is no hope. But if hope lies with the proles, and that extraordinary example of the proles, is this woman singing a song about lost love and memory and yearning while hanging out diapers.

She's committed to the past through the lyrics of the song. She's committed to beauty through being this extraordinary singer, cockney accent, but also exquisite voice. And she's committed to the future with these diapers she's hanging out. And he describes her as a kind of goddess, that she could have been there for a thousand years, just this tremendous sense of power. And to find that at the heart of the book was really exciting and not at all how I had ever interpreted the book before or how I'd ever interpreted myself before.

So yeah, so "1984" changed shape thanks to "Orwell's Roses," which I should add is not only a book in which roses give me some new ways of thinking about Orwell, but Orwell gives me some new ways of thinking about roses, and by extension, flowers, plants, and the natural world. And so it's very much a book about climate change, plants and carbon fixing and carbon sequestering, botany, agriculture, bread and roses, wheat, and lots of scientific discourses and political controversies, and the rest. And yet mysteriously, I think it all fits together.

I think a lot of people who aren't writers have this image of writers as people who live in their heads, especially kind of political writers like Orwell, very in the clouds, not with feet on the ground. But in my experience, I'm a writer, I know a lot of writers like what we do, and they do – they're often foodies, they're often gardeners, they're often people who have hobbies with their hands, like Orwell and his gardening. Why do you think that is, that writers are so – I think they're disproportionately drawn to wanting to do things with their hands when they're not working.

I'm an avid cook and joke that if I didn't have friends and family, I'd have to pull in strangers off the street for dinner. And I love the farmer's market. One of my idyllic experiences over the last 30 something years has been listening to KPFA's country music on the radio on the weekend while preparing food for people who haven't yet arrived. And for me, cooking is the exact opposite of writing. It engages all the senses, it's visual it has flavor, smell, texture, it's hands-on, but also, you know exactly what you're doing. The souffle collapsed, the pie had perfect flaky crust, the soup needed more salt or was delicious. People respond to it immediately, hopefully by eating it, and then you're done.

Whereas you write a book, you don't know what you did. The only people who will get back to you usually are cranky people who disagree with you, want to pick a fight and a few reviewers. It will just float out there in the world like a message in the bottle. And sometimes, almost by accident or someone will take the effort to communicate with you, you'll find out that it had some wonderful impact, but mostly, you don't. And it happens,I wrote this book last year. It's coming out a year after I finished the first, more than a year after I finished the first draft. And maybe in 10 years, it will have some interesting impact on someone that I'll never know. So I think that just the tangible, the direct, the sensory.

Also, I think a lot of writers, and I cannot pronounce the name of the great Japanese novelist who wrote "What We Talk About When We Talk About Running," but I'm a runner. I actually just came in from running on the beach where I got sea birds and a dead shark and a dead cormorant, and the little patterns the wind makes on the sand, and I think that we all need a certain amount of, just ordinary human beings, all human beings, not just writers need some grounding, and writers are not exceptional. But what also interested me with Orwell is, in a way, this book is written against the left, which is something he was doing a lot with his own writing. There's a sense in the left, which I'm often around, grew up among, that every pleasure is somehow an indulgence and needs justification, or is maybe just unjustifiable, that you should be 24/7 fighting for the revolution, and we shouldn't have any nice things until after the revolution or when anybody else is suffering.

And there will always be somebody suffering after the revolution is a fictional space, so it basically says don't enjoy yourself. And I also think a lot of people on the left think somehow their miserable, austere suffering is what they're offering up. And I just don't think anyone starving to death, or in a refugee camp, or being tortured, or under threat from a death squad is like, "Yeah, but some Americans are sitting around being really miserable in solidarity, and that makes me feel awesome." All I really want is for us to actually work for their rights and safety and well-being.

And it's okay if we bake a cake, or go on a nice run, or plant a garden. And Orwell did all that stuff, and it was not just compatible, I think, necessary.

I think that tendency on the left got worse during the pandemic where there was a real sense that any kind of pleasure was somehow not in solidarity with the misery we were all sort of sharing under this pandemic.

God knows I have been chastised for my minor pleasures. I got chastised by some complete stranger in the UK for mentioning buying a pretty shirt in June of 2020, and then going to a George Floyd protest. And she was like, "You're trivializing it." And I was like, "Lady, I was at the Rodney King uprisings. I was at – I've been going to protest my whole life. I will probably be going to anti-racist protests my whole life. Every now and again, I'm also going to buy a shirt, and sometimes, those things will coincide." It's not like the world stopped because there is racism, and that those things can coexist. And then Orwell was such an impeccable example, because he is treated as Mr. manly, austere, committed, et cetera, and there's this funny – Actually, to Sam, I said, "I felt like I was pelting Orwell with sissy flowers." So I felt like if Orwell can do it, we've all got covered.

More stories you might like:

Shares