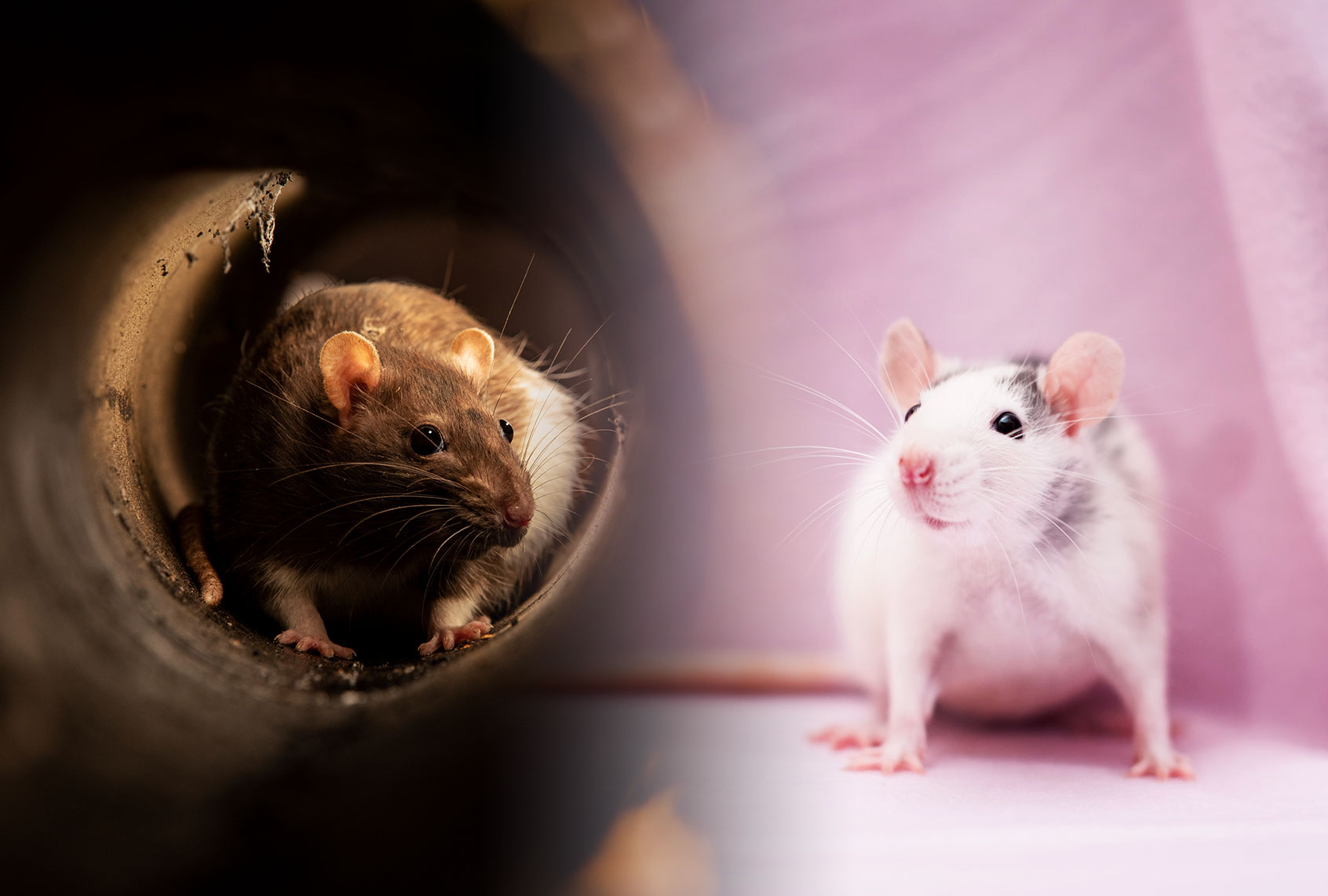

In February of 2020, my family got fancy rats. Our much-loved cat, Clifford, had died a few months earlier and my eldest, then thirteen, enlisted her younger siblings to advocate for a new pet. She made a PowerPoint, interviewed her brother and sister on camera, and knowing a creature of higher order was off the table (“I can only handle something that lives in a cage right now,” I’d told them), came up with various other options. Rabbits, sugar gilders, chinchillas, and hamsters made the list. But the animal she truly championed was a rat.

She narrated from the slide: “Rats love to show affection, to get pet and scratched. They also love to play games like, hide ‘n’ seek, tug-of-war and more! All rats are individual, they each are themselves and even the dumb ones are affectionate too. Rats are good for all ages. They only need one hour of love a day and they are good in spaces of any size. They are non-allergenic pets too! They are good with other rats! They will also eat almost anything!”

So we got two, Snowball and Dill. Soon after, my partner, a rat skeptic if ever there was one, even mused, “If I had known how cute they’d be, I would have signed off a lot sooner.” I also grew quite fond of the pair. Even when their litter smelled. Even when they gnawed through not one, but two cages, and escaped. Even when — contrary to my daughter’s PowerPoint assurance — they did indeed bite.

But at the same time as we were learning to love our pets, we were also being confronted with a new challenge. Street rats. I’d lived in my neighborhood for almost fifteen years and on my block for five. It was clear there were more rats recently. This, we were told, was the result of the newly arrived pandemic. Restaurants were closing and without their garbage, rats were starving and in search of food.

RELATED: Our war against urban rats could be leading to swift evolutionary changes

The pandemic meant that while rats were out and about, we were home. Though we had historically been subway people, we had moved into a place that actually came with both a driveway and a backyard. These were luxuries far beyond any I had before known in the various apartments I had inhabited during my two decades in the city. And so, with a driveway we got a car, a 2003 Camry hand-me-down from my in-laws. We would use it maybe once a week to grocery shop or do errands, or occasionally to get out of town.

But as we sheltered in place, those trips decreased. For months we had no need to drive. We biked and walked and just didn’t go very far. As a result, the car sat more idle than usual. In fact, it had been well over a month since we had driven it when my son fell off his bike, broke his wrist, and in one of the most dire months of the first pandemic wave, had to go to the hospital.

But when I opened the car door to transport him, I was hit by an odd smell. Then a grinding sound emerged as I tried to start the ignition. It was clear that the car was out of commission.

So we took a Lyft.

After returning from the hospital, my partner and I did some exploring and realized that rats were not only racing around our block, but they had also invaded our engine. We went on the attack. We took the car to the first of many mechanics, cleaned out the nest, and tried every home remedy — moth balls, peppermint spray, special spicy rat tape — that YouTube could offer. We called exterminators, set up traps and fortified our fence. We put in high frequency anti-rat alarms, scrubbed the driveway, and floored the gas before driving in order to give any rats inside a chance to escape.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

But this was a battle we continued to lose. Every time we thought we had conquered the situation, telltale rat droppings would appear. Or we would try to start our car and discover that rats had eaten through yet another wire. Or we would pop open the hood, only to have a rat leap out.

Worst was the day I left my house and noticed that the windows of the car were all blacked out. I walked closer and saw that the car was so infested with flies that one could not even see in. Flesh flies, the internet told me. These thrived on the dead. You could tell the breed by their red eyes. I later learned that a rat had died in an air vent and this was the grotesque result.

But it didn’t stop there. The rats were not only intent on destroying our car, they also discovered they could tunnel under the fence of our small backyard and dart across a swatch of patchy clover in a move that would startle the guests we had only slowly begun to socialize with outside.

We doubled down, got rid of the car, tried to block off the driveway, and dug a trench along the back fence into which we sank chicken wire and filled with pea gravel. We conferred with neighbors about the source of the vermin, and called the Department of Health to report an abandoned car, which we blamed, in part, for the infestation. Despite the fact that my own car seemed to be towed every time I was two minutes late returning to a meter, I was told that since the vehicle had valid license plates, and even though it had been there for well over a year accruing a mountain of tickets for failing to move during alternate side parking, it simply could not be removed. “Why don’t you just take off the plates yourself,” a helpful sanitation worker suggested to my partner while writing yet another ticket on the car. He declined. (For the record, it has now been two years. The license plates are no more. Yet the car remains.).

But while we just wished a swift death to our outdoor rats, our indoor rats were living the high life. Snowball and Dill had a four-tier cage, chew toys and hidey holes, treats, exercise balls, and attention. That is until we noticed that Dill looked pregnant. This was surprising since we had been assured at the pet store that both rats were female.

I found an online vet service and got a different diagnosis. A mammary tumor.

The next day I put Snowball in a hamster carrier and took the subway to an animal hospital. Due to Covid restrictions, I sat outside the office on a folding chair in a light drizzle and talked to the vet over the phone.

“I’ll give you the name of an exotic pet surgeon,” she told me. “Now, these tumors do grow back, but she can remove it temporarily.”

“Um, what if I don’t want to do that?” I asked.

“Well, you could try oral antibiotics twice a day in case it gets infected.”

“And if that seems a bit much?”

“You could do a hot compress massage on the tumor for 30 minutes three times a day.”

“And what if I just let her be?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s fine too,” said the vet. “Just bring her back if she stops eating or drinking or playing.”

Eventually, the tumor was almost larger than the rat. She could no longer climb up the ramps in her cage. And soon after, she did, in fact, stop eating and drinking and playing. It was clear Snowball was not in good shape.

I told the three kids that Snowball was too sick to have a happy life and that the vet needed to put her down. There were some tears and tender goodbyes. For my littlest, then five, I pulled out a book I had turned to in previous moments of human and animal death, 1987’s “The Tenth Good Thing About Barney.” This tells the story of a pet cat who dies and then follows the debate between two children about whether the cat was in the ground, as one believes, or in heaven as the other does. We were a blended family, and my kindergartener regularly grappled with the impact of death, wondering who she and her siblings would live with were her parents to die. So it made sense that, despite the existential questions posed by Barney, her biggest concern was not about what the afterlife would bring Snowball, but rather what would happen in the present.

“Won’t Dill be lonely now that Snowball is gone?” she asked. The other children wondered the same thing.

And that was an issue. Rats are social animals and need companionship. The kids just assumed that we would get her a replacement friend. But I imagined something different. A year and a half of battling pandemic rats had taken its toll. Rodents were still a fixture on our block, darting out as we walked by, occasionally appearing flattened in the middle of the street, and leaving repugnant evidence of their presence in the form of droppings and gnawed open trash bags. Sitting in our living room, we had also become attuned to a particular type of scream that indicated the occurrence of a pedestrian / rat encounter.

The thought of continuing to nurture indoor rats, while battling those outside, was becoming too much to consider. So I joined an online group for rat owners and found Dominic. He had eight pet rats already. They only ate organic food and would free roam in his apartment for two to three hours a day. They loved alfalfa and ear scratches. He’d be delighted to adopt Dill.

The day after Snowball’s last trip to the vet, Dominic arrived. He coaxed Dill into the new pink carrier that I had bought for the occasion, made polite small talk, and then headed back out to the train.

As we waved goodbye from our stoop, I heard a telltale scream indicating a sighting. “Oh,” I tried to chuckle, embarrassed to have Dominic note our block’s situation even as he held a rat in his hand, “I’m sure it’s nothing.” Then I hurriedly closed the door to my newly rat-free home and imagined a time when I would not have any street rats to contend with either.

More stories from Salon about rats: