By this point, we know what we’re going to get sitting down to watch a Wes Anderson movie. (That is, if we even know a new Wes Anderson movie is coming out at all.) Audiences will be treated to a richly detailed world, filled with quirk-forward characters and verbose musings about life, love, travel, art, the human condition, fine cuisine and the inevitability of our demise. A handful of recognizable faces will pop up; Bill Murray, Willem Dafoe, maybe one or both of the Wilson brothers. Their dialogue will be unapologetically fast-paced and dryly humorous. The entire affair will be a grab-bag of Anderson’s trademarks, and hopefully, the writer-director will carve out room to find something unique to say amid all of his wheel-spinning.

Anderson’s style wasn’t always so predictable. It used to be that going to see one of his films guaranteed a visual feast that would bring untold narrative delights, threaded throughout any one of his movies, so the story worked in tandem with the filmmaker’s creative signatures. Over the last half-decade or so, the bond between style and story has cracked. Though Anderson’s conceptual scope is as bold and sprawling as ever, his ideas now bear the weight of his visual prowess. No longer the niche filmmaker he once was, Anderson has long since crossed over into the mainstream, buoyed by a culture that has turned esotericism into a commodity. Now, Anderson’s films are picked up and picked apart for moodboards and generative AI prompts. They’re part of a recently announced, homogenous Criterion Collection box set, too uniform to speak to the array of colors and characters in its contents. Why put your whole heart into something if the audience will ignore your intention in a race to associate themselves with an aesthetic?

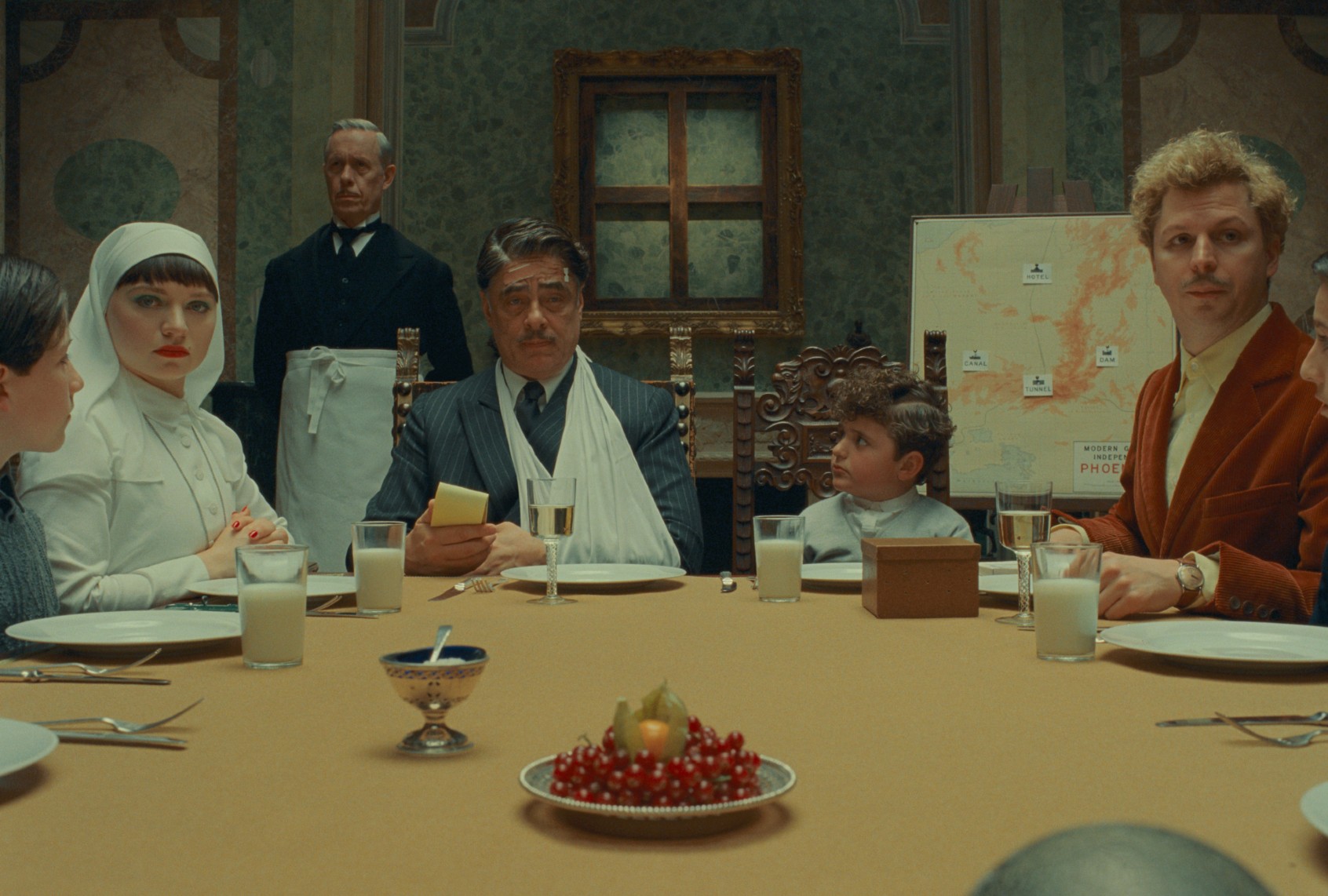

(L to R) Benicio Del Toro as Zsa-Zsa Korda, Michael Cera as Bjorn and Mia Threapleton as Liesl in director Wes Anderson's "The Phoenician Scheme" (Courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features)

(L to R) Benicio Del Toro as Zsa-Zsa Korda, Michael Cera as Bjorn and Mia Threapleton as Liesl in director Wes Anderson's "The Phoenician Scheme" (Courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features)

“The Phoenician Scheme” has Anderson pulled in two different directions, caught between art and business in a time when the two have never been more disparate. The resulting product is just that: a product, with all of the matte pastel appeal of Anderson’s oeuvre, yet little of its memorable charm.

In Anderson’s latest, “The Phoenician Scheme,” the director grapples with being seen as a brand instead of a storyteller. The film follows Benicio Del Toro’s Zsa-zsa Korda, an assiduous businessman hell-bent on developing a fictional version of 1950s Phoenicia into a profitable economic system, from which he and his band of cohorts will reap the rewards. Zsa-zsa ropes his only daughter, a nun named Liesl (Kate Winslet’s daughter, Mia Threapleton), and a brilliant tutor, Bjørn (Michael Cera), into his farce, toting them along for a dangerous journey. The film is wry and beautifully realized, one of Anderson’s best efforts in years. It’s also one of his coldest, with all of the wheeling and dealing of commerce and incessant business jargon seeping into the movie’s bones and leaving the viewer emotionally disconnected. “The Phoenician Scheme” has Anderson pulled in two different directions, caught between art and business in a time when the two have never been more disparate. The resulting product is just that: a product, with all of the matte pastel appeal of Anderson’s oeuvre, yet little of its memorable charm.

Just because Anderson is making glorified Funko Pop! figurines doesn’t mean that “The Phoenician Scheme” is a bad film — or perhaps more accurately, an uninteresting one, given that relegating works like Anderson’s to a term like “bad” is unfairly reductive. In fact, the movie sits miles from uninteresting. Its central trio of acerbic misfits is Anderson’s most fascinating collection of characters in some time, co-conceived alongside his longtime collaborator and friend Roman Coppola, who co-wrote 2021’s “The French Dispatch” and 2023’s “Asteroid City.” Unlike those two films, which played with narrative form in an attempt to shake up the audience’s expectations for an Anderson production, “The Phoenician Scheme” is relatively straightforward. It’s a story told in chronological order, rarely dipping into the director’s so-loved narrative asides, which amiably guides the viewer through a deluge of fast-talking, corporate jargon to keep them in the film’s grasp throughout all 102 minutes. Much like jumping into “Succession” or “Industry” totally blind, if you wait it out, you’ll come to understand what’s happening eventually.

After a suspicious plane crash that ends in another one of Zsa-zsa’s outlandish near-death experiences, the tycoon suspects that the several recent attempts on his life are connected to his plans to develop Phoenicia. To protect the titular scheme already in motion, Zsa-zsa reconnects with Liesl, who is just days from taking her holy vows and spending the rest of her life in a convent as a devoted servant of God. Yet, as much as she rejects the flair of her father’s lifestyle, Liesl can’t help her affection for the glitzy, impious pleasures Zsa-zsa so adores, making Threapleton the coolest nun since a habit-wearing Lindsay Lohan took down conservative cowboys in Robert Rodriguez’s “Machete.”

(L to R) Benicio Del Toro as Zsa-Zsa Korda, Riz Ahmed as Prince Farouk, Michael Cera as Bjorn and Mia Threapleton as Liesl in director Wes Anderson's "The Phoenician Scheme" (Courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features)

(L to R) Benicio Del Toro as Zsa-Zsa Korda, Riz Ahmed as Prince Farouk, Michael Cera as Bjorn and Mia Threapleton as Liesl in director Wes Anderson's "The Phoenician Scheme" (Courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features)

Liesl’s sunglasses-wearing, pipe-smoking, lipstick-stained disaffection is a joy to take in, but Threapleton brings so much more to “The Phoenician Scheme” than devout detachment. Zsa-zsa wants Liesl to be the sole heir to his estate, and she agrees, so long as he’ll help Liesl discover who murdered her mother. (Zsa-zsa repeatedly swears he had nothing to do with her death.) Zsa-zsa’s business exploits may be the film’s primary thrust, but Liesl’s journey to actuality is its most invigorating plotline, carried ably by Threapleton with cutting sarcasm and genuine emotion behind her steely, green-eyed gaze.

The film, unfortunately, needs a character like Liesl to carry it. While Del Toro’s comedic timing has never been better, and Cera’s thick Norwegian accent and dopey peculiarities feel right at home in Anderson’s world, Zsa-zsa and Bjørn would be lost without Liesl. Perhaps that’s the point Anderson is making, that suave business magnates and silly scientists alike will be undone by their inherent, world-conquering machismo. But Cera and Del Toro’s characters are too thinly written for that idea to feel thematically cogent. Amid Zsa-zsa’s enterprising adventures, Anderson loses sight of his protagonist’s initially unmistakable sensitivity, once lurking just beneath the surface. It’s frustrating to get a taste of this intimacy, only to watch it slip through our fingers, especially when each frame of “The Phoenician Scheme” looks so meticulous that one wishes the screenplay itself could match its authors’ eye for physical beauty.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Instead, Anderson and Coppola are preoccupied with the minutiae of trade and commerce. Their determination to write authentic lingo about investment gaps and percentages is admirable enough, but that means little when the average viewer is unconcerned with authenticity, especially in a film so stylized. They eventually move what would otherwise be the film’s centerpiece dynamic — the burgeoning father-daughter connection between Liesl and Zsa-zsa — to the back burner, forgetting about their relationship until flames threaten to consume it. Liesl and Zsa-zsa’s oft-neglected kinship is sweetly tied up in the end. But by then, it’s too late; Anderson’s spent so much time assessing how his characters can mind the financial gap that he’s forgotten to tend to the narrative ones in his screenplay.

It'd be foolish to think that an artist like Anderson wouldn't be chaffed by seeing his style replicated by unimaginative wannabes, typing sentences into AI image generators. Maybe this is Anderson’s way of saying that stealing something beautiful in the name of “innovation” comes at a great cost, not just to the original artist but to the public consuming this bastardized “art.”

It’s hard not to notice that “The Phoenician Scheme” continues the director’s late-period trend of trying to forge resonance where there is little. In his work alongside Coppola, Anderson crafts small pockets of earnest depth amid turbo-accelerated storytelling, which are typically the scenes that have the biggest impact on viewers. (Think: Margot Robbie’s brief balcony scene in “Asteroid City.”) His films have a rhythm to them. They move rapidly and are so bountifully detailed that neither the eye nor the brain can keep up entirely. So, when Anderson slows the pace, the audience understands that it’s time to feel. It’s a trick that works almost every time, but like most clever tricks, seeing it happen enough times will dull the impact, no matter how impressive the construction is.

Director Wes Anderson on the set of "The Phoenician Scheme" (Roger Do Minh/TPS Productions/Focus Features)

Director Wes Anderson on the set of "The Phoenician Scheme" (Roger Do Minh/TPS Productions/Focus Features)

While Anderson’s go-to formula made him a household name, his penchant for idiosyncrasy and fastidious precision has been a double-edged sword. “The Phoenician Scheme” spots a filmmaker writing himself to the edge of a cliff. The stories have gotten colder; the characters are predictable and plucked from a stock of go-to traits. Anderson’s work has become mired by his ambitions to create adult fairy tales so outsized and wondrous that they’re undeniable, no matter how repetitive they are. And now, with his latest film — his third in five years — he’s come back down to Earth. Industrialism has replaced love. Duplication has replaced creativity.

Perhaps this is part of Anderson’s response to those frightening AI prompts that jacked his style. (I’d say it’d be foolish to think that an artist like Anderson, whose work is so scrupulous, wouldn't be chaffed by seeing his style replicated by unimaginative wannabes, typing sentences into AI image generators instead of picking up a camera.) Maybe “The Phoenician Scheme” is Anderson’s way of saying that stealing something beautiful in the name of “innovation” comes at a great cost, not just to the original artist but to the public consuming this bastardized “art.”

That idea isn’t out of the realm of possibility, but if it’s intentional, Anderson never makes it overt enough for viewers to grab onto. Even as he’s faced with people trying to swipe the method he’s spent years perfecting, Anderson’s too good-natured — possibly too content in his legacy — to swipe back. But what once made Anderson’s work so irrefutable was his delight in taking big swings, whether in visual form, narrative writing, or both. And, granted, there are some new, kinetic camera movements and brief experiments with structure in “The Phoenician Scheme” that feel like the seedling of something original, but they aren’t enough to sustain consistent hope. Should he ever swallow his pride and burn his pastel fables to the ground, at least just once, Anderson might be able to forge something new and innately memorable from the ash. Until then, they will remain bright, beautiful and bloodless.

Read more

about Wes Anderson's expansive career