Last Christmas, I was overcome by the sudden urge to watch “Home Alone.” Not the wildest or most unexpected impulse, given the season, but I’d shockingly only seen the classic once before in my life, and needed a healthy dose of ’90s phthalo green nostalgia to kick my holiday into high gear. To my great surprise, I had no memory that John Candy had a stellar bit part in the film as a modest Midwestern polka player. The cameo made the smile that was already stamped across my face grow even wider. Before long, I found myself following “Home Alone” up with “Planes, Trains and Automobiles,” another Candy comedy I hadn’t seen in years. And though I found it less charming than I remembered, I still wept during the unforgettable third act, when Candy’s obnoxious shower ring salesman, Del Griffith, finally stops his relentless chatter to admit just how lonely he is. The confession is a startling moment of humanity, designed to catch the viewer off guard. But it’s also what made Candy so beloved: As funny as he was, he could turn on a dime to remind us that even the grandest personalities are human at their core.

In an industry where phoniness and arrogance are stipulated in the fine print of an actor’s soul-selling contract, Candy remained the genuine article until his untimely death in 1994. Before Candy died of a heart attack at just 43 years old, the Canadian comedian achieved world fame for his deft improvisational skills and joyful presence. His affability was undeniable, largely because Candy was as kindhearted and authentic in real life as he was onscreen. At the start of Colin Hanks’ new Prime Video documentary, “John Candy: I Like Me” — named after another one of Del Griffith’s most moving lines — Candy’s old friend Bill Murray struggles to remember anything juicy he could reveal about Candy’s life. “I hope that what you’re producing here turns up some people who have got some dirt on him,” Murray jokes. After some thinking, Murray recalls a time he and Candy did a stage reading of a play directed by Sydney Pollack, and sighs with relief. “Oh, this is a bad thing to say about him. Good, I’m glad I thought of something.”

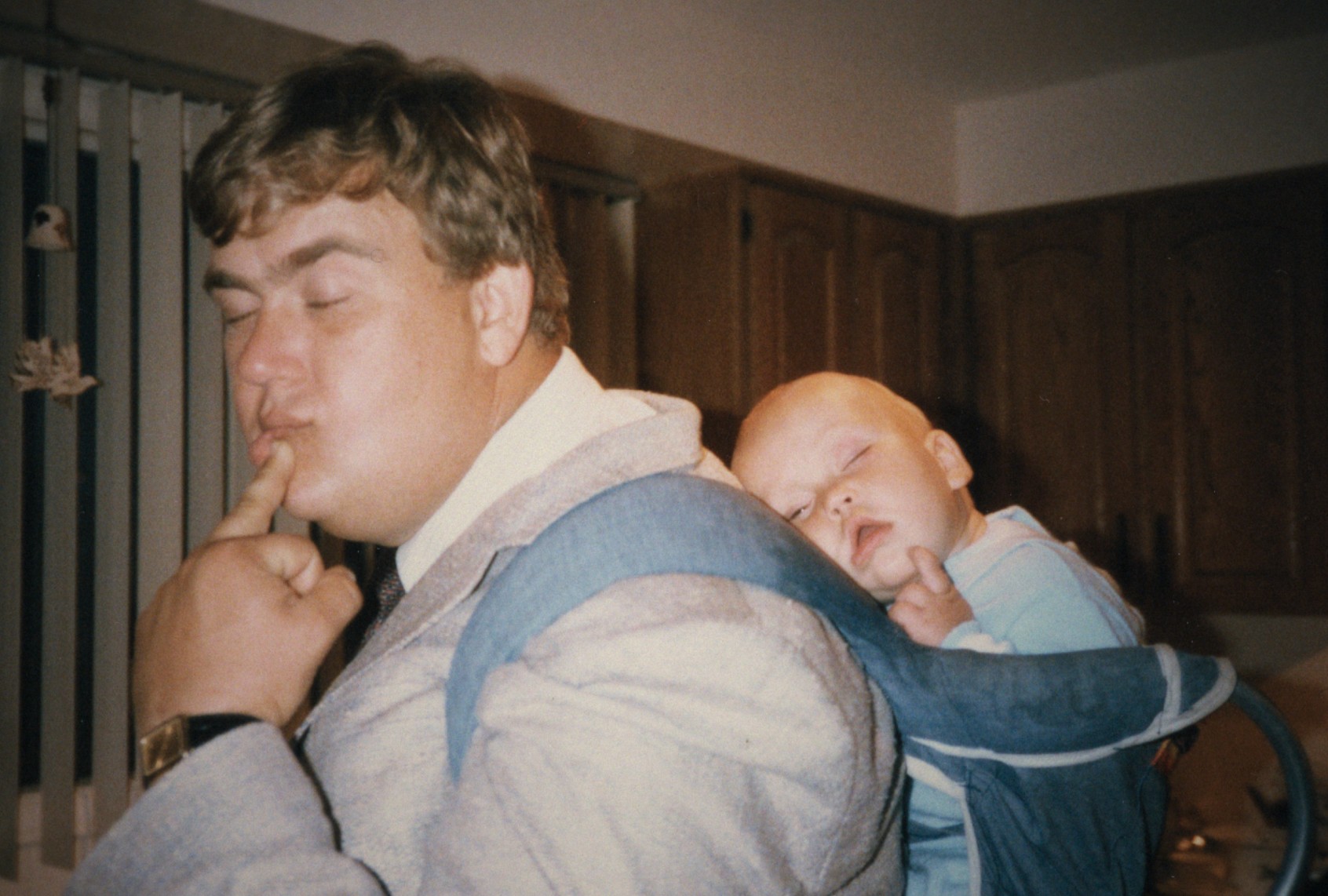

(Prime Video) John Candy, as seen in “John Candy: I Like Me”

It’s funny how just the grainy, washed-out look of videotape can conjure so much melancholy. Now, everything is crisp — too crisp. There’s nothing we don’t miss, no grim detail that isn’t slammed over our heads, and in sharp, digital picture.

As it turns out, Murray’s story doesn’t besmirch Candy’s memory at all. His tale is one among hundreds in the documentary highlighting just how much of a people-pleaser Candy was. One of his few notable flaws was that he cared too much about others, and that he wanted to devote so much of his time and energy to making them happy — occasionally at his expense. Though there are some grim tales in “I Like Me,” none of them point to a hole in Candy’s personal character. There are no shocking revelations of immorality or stories of substance abuse that aren’t already widely known. Instead, the documentary is a star-studded, rose-colored recollection of better days, a look back at an era that didn’t seem so fraught with deception and morbid artificiality. While Hanks opts for a hagiographic approach to his subject, it’s difficult to imagine that, as Murray suggests, there are many other routes to take when discussing the life and legacy of a figure so universally beloved. Rather than root around for scandal, “John Candy: I Like Me” goes all-in on its feel-good mission, stressing that virtue is a quality so timeless that it can stretch far beyond mortal bounds.

With so much fantastic archival footage at Hanks’ disposal, it’s hard not to be stricken by just how much the world has changed in the 30 years since Candy’s death. It’s funny how just the grainy, washed-out look of videotape can conjure so much melancholy. Now, everything is crisp — too crisp. There’s nothing we don’t miss, no grim detail that isn’t slammed over our heads, and in sharp, digital picture. Social media’s predatory algorithms and the monotonous drone of 24/7 news feeds ensure that we are constantly dogged by things we don’t want to see, even if the TikTok “For You” page or Instagram’s “Discover” section convinces us that we do. And good luck if you try to get off the ride. Humans are constantly pulled between the belief that we should stay informed and the desire to stick our heads in the sand. Even a stroll outside in the brisk autumn air can be dampened by the stray glimpse of a red baseball cap.

If you’re anything like me — that is, frequently fraught with fear that humanity’s loss of compassion is not only spiraling out of control, but irreversible — Hanks’ documentary is a godsend antidote to contemporary anxiety, if only for two hours. That does not, however, mean that the entire film is a laugh riot. Keep a box of tissues close by: I was a blubbering mess two minutes in, when Hanks follows Murray’s cold open with one of the eulogies from Candy’s funeral. It may seem like a whiplash decision on paper, but in practice, it’s a fantastic and highly emotional introduction to Candy’s work and legacy, from his beginnings on Canadian staple “SCTV” to his final roles, especially for any viewer who may not already be intimately aware of either. From there, Hanks keeps things largely chronological, but only briefly touches on Candy’s childhood to form the thread that “I Like Me” unspools to its end.

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Just before Candy’s fifth birthday, his father died of complications with heart disease, a sudden event that was largely swept under the rug by Candy’s family during his childhood. Candy’s son, Christopher, and his daughter, Jennifer, partially attribute Candy’s chronic anxiety and health problems to this massive childhood trauma and the startling lack of response to it. Candy’s children convey the impact of losing a parent at a young age, and how deeply unfair it is, especially if no one in the family is willing to talk about it. And though their experience was ultimately different, the cyclical nature of death that plagued Candy was set from a pivotal age. When he recalls the moment he told Candy that John Belushi died in 1981, Candy’s “SCTV” costar Dave Thomas tearfully recalls his friend saying, “Oh God, it’s starting.”

(Prime Video) John Candy, as seen in “John Candy: I Like Me”

Even amongst all of life’s pressures and its difficulties, it’s easy to live with integrity if you keep it by your side at all times. Candy treated everyone, even the children he worked with, as respected equals, a rarity in a business where power and money keep the playing field in constant flux.

But according to his family, friends and colleagues, the knowledge of life’s temporality was also what made Candy the kind, compassionate man he was. Hanks pulls no shortage of favors, calling in a remarkable spate of talking heads, from Canadian comedy cohorts Catherine O’Hara, Eugene Levy and Dan Aykroyd, to Tom Hanks, Macaulay Culkin, Conan O’Brien and even some lively inclusions from the legendary Mel Brooks, who directed Candy in 1987’s “Spaceballs.” Hanks directs with an incisive hand, careful not to overlap too many fawning praises, and instead ensuring that the film is chock-full of personal stories and precious memories that speak to Candy’s character, rather than having the interview subjects relay it plainly through trite, he-was-one-of-a-kind platitudes. Rare outtakes from films like “Home Alone,” unseen footage and home videos round out the film and give it a piercing intimacy. Perhaps it’s because two of Candy’s memorable performances are from films that take place during the holiday season, but just watching “I Like Me” feels warm in the way that a joyful winter holiday does.

There are some less fluffy bits, yes; mentions of Candy’s capacity to hold a grudge and his almost uncharacteristic desire to enlist in the Vietnam War after high school come up. They’re skimmed over, but not in a manner that feels reluctant or incurious. Rather, Hanks seems to suggest that these are as in line with Candy’s morals as any of the stories told by his friends and family, indicators that the actor believed in trying to do what was right, even if he didn’t always take the most clear-minded path.

Candy’s pursuit of goodness comes up repeatedly throughout “I Like Me,” to the point where a viewer can understand that, even amongst all of life’s pressures and its difficulties, it’s easy to live with integrity if you keep it by your side at all times. Candy treated everyone, even the children he worked with, as respected equals, a rarity in a business where power and money keep the playing field in constant flux. But for Candy, fame was seemingly never the goal. He liked to make people smile and feel as grateful for life as he did, and that was the place his massive influence was born. Thirty-one years after his death, that impact is still felt, still worth examining and celebrating. We have to make time for the good as much as we do the bad, allow space for our laughter as much as we do our tears and our terrors. It may be the most overused idiom to ever exist, but life is short; the only way to live it is to try our hardest to like it.

Read more

about documentaries worth your watch