Tim Curry’s new memoir, “Vagabond,” starts with an anecdote that takes place in 1976, when Curry moved to New York — and not just to New York but to an apartment directly behind the Waverly cinema, where midnight showings of “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” had become a surprise hit that drew dedicated crowds weekend after weekend. Curry hadn’t seen the film since it came out years before to a bruising critical and financial response, and was looking forward to it. But when he called the Waverly box office and asked them to set aside a few tickets, he couldn’t convince the woman there that he was, in fact, Tim Curry. When he did attend, though, the audience took notice, and soon enough that same woman tried to bounce Curry from the theater, furious with the giddy mayhem and, I’d guess, chaotic level of horniness his presence generated.

Curry has simply never played a memorable character who was also just a normal, chill guy, and that’s a big part of why he’s so staunchly beloved among ’80s and ’90s kids.

The next bit of the story unfolds as expected: He let the woman rant for a bit before showing her his passport and watching “her haughty expression collapse.” The kicker surprised me at first — the actor, long known to be gracious and humble, refused to accept the apology and instead stalked coldly out of the Waverly. But of course it makes sense: The man behind Dr. Frank-N-Furter, one of cinema’s most flamboyantly indelible villains, can’t just sit back down after a moment of such dramatic comic perfection.

Curry doesn’t describe how the audience reacted to his dramatic flounce from the theater that night, but I’m pretty sure those in attendance dined out for years on the story of “I Was There When Tim Curry Made the Waverly Manager Die of Embarrassment.” (When my friends took me to see “Rocky Horror” at midnight 12 years later, at the same theater, I met a woman in the bathroom wearing a top hat and tap shoes who still hadn’t quite gotten over it.) But the story is the perfect start to a thoughtful — but hardly analytical — book of recollections by an actor who made his name fully committing to the bit, whatever it was.

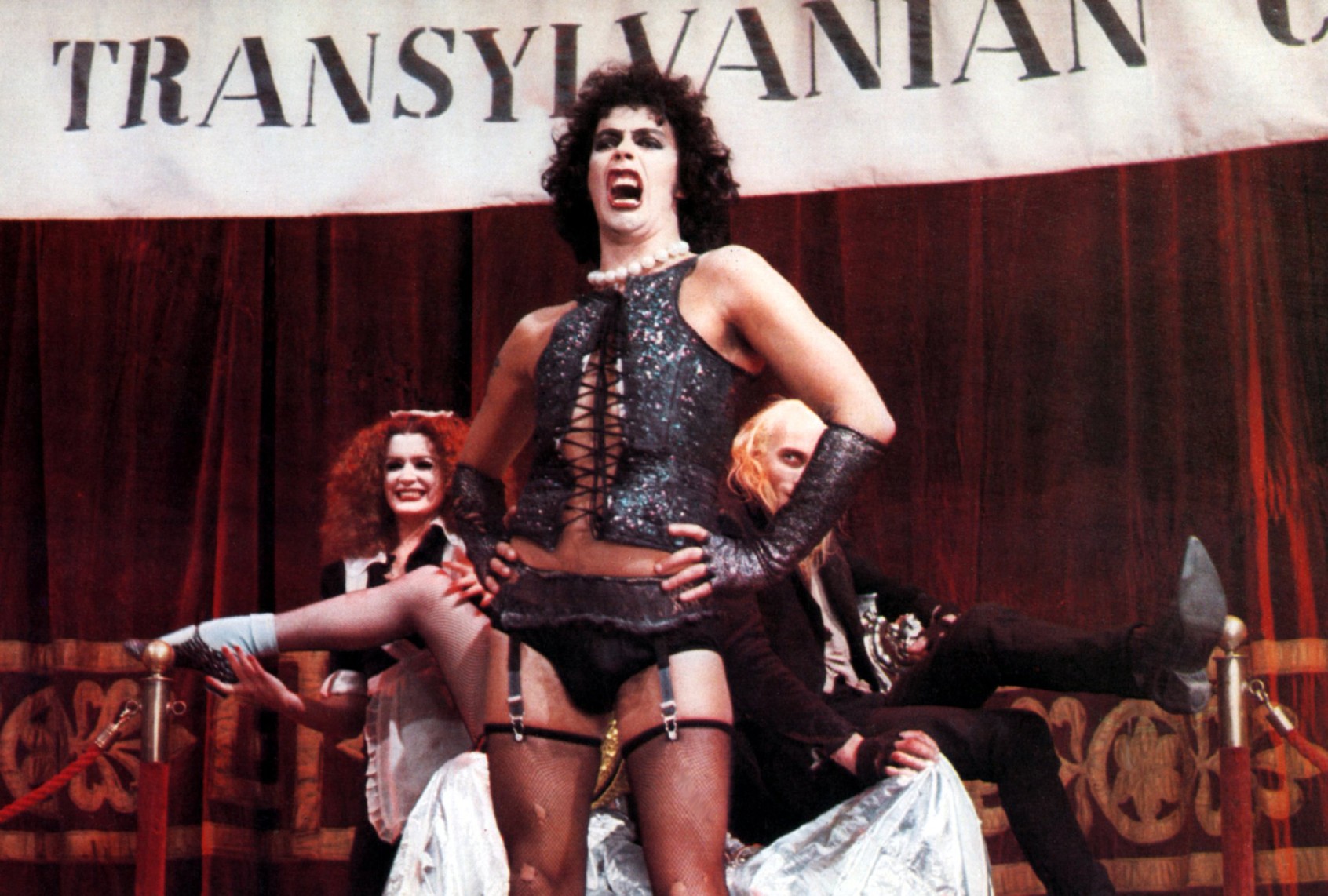

(FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives via Getty Images) Tim Curry as Dr. Frank-N-Furter in “The Rocky Horror Picture Show”

I used to think that a dividing line between Gen X and Millennials was which iconic Curry character they grew up with: For X, it was “Rocky Horror”’s gender-bending mad scientist/sex monster Dr. Frank-N-Furter, terrifying murder clown Pennywise from the original movie of “It” and the manic, secretive butler Wadsworth in “Clue” — each uniquely deceitful and menacingly charming. But the characters that would have introduced Millennials to Curry — the smarmy hotel concierge Mr. Hector in “Home Alone 2: Lost in New York,” Long John Silver in “Muppet Treasure Island,” and the noxious spirit Hexxus in “Fern Gully: The Last Rainforest” — are also deceitful, also charming, also menacing.

Curry has simply never played a memorable character who was also just a normal, chill guy, and that’s a big part of why he’s so staunchly beloved among ’80s and ’90s kids. When I picked up his new memoir, “Vagabond,” I assumed that it would include lengthy sections on some of the inspirations behind this collection of seductive villains. And it did, but not at all in the way I expected. Acting came naturally to Curry without a lot of soul-searching or researching; when John Huston, who directed him in “Annie,” asked what he planned to do with the role of the, yes, deceitful and charming Rooster Hannigan, Curry replied, “Well, I thought I’d show up.” (Side note: Who else had no idea John Huston directed “Annie”?)

But Curry drops the Rosetta Stone within the first two pages of “Vagabond” as he does what all celebrity autobiographies do, taking the reader back to his childhood, introducing his family and, as stated bluntly by the first chapter’s title, setting the scene. When he was a year old, his father’s work as a Navy chaplain took the family to Hong Kong, where, Curry writes, his mother entered a photo of him into a contest called “Most Beautiful Baby in Hong Kong.” It won, something which his mother “later told me, without the slightest uptick in enthusiasm.” By the end of the book’s third chapter — after Curry has traced a lonely childhood moving from place to place until the sudden death of his father — everything comes into focus. It’s not easy to make “I’m like this because of my mother” feel like an original motif, but Curry pulls it off; in his empathetic but unsentimental accounting of a child’s love and affection scorned and spurned, you can practically feel a chill rising off the page.

“Was I able to play Pennywise — the murderous clown of ‘It’ or the malevolent, alluring Cardinal Richelieu of ‘The Three Musketeers’ because of terrifying childhood memories of my mother? Of course not. Did those memories assist in helping me understand and embody those characters? I believe they did,” Curry writes — and, almost as if he can’t help himself from going even further, adds, “And when I was playing Dr. Frank-N-Furter, and emerged from the refrigerator having just murdered Meat Loaf, swinging an ax, was I thinking of her? Well, between us, yes.” Curry’s honesty and humor don’t explain his villains because his villains came to the screen already legible, graspable, not needing backstory to explain them. But it’s an incredibly moving way to give context to those villains, to re-envision them knowing that each one had some wrenching, primal heartbreak at its core.

(Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images) Tim Curry, 1974

It’s not easy to make “I’m like this because of my mother” feel like an original motif, but Curry pulls it off; in his empathetic but unsentimental accounting of a child’s love and affection scorned and spurned, you can practically feel a chill rising off the page.

With “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” celebrating its 50th anniversary and “Clue” its 40th, 2025 has been a landmark year for Curry. But a tension that’s consistent through “Vagabond” is the actor’s desire to express how much the craft of acting means to him, but at the same time, to express horror at the idea that the reader might think that he thinks he’s a big deal. The result is that the book — a tour through his best-known films, favorite stage roles and unexpected delight in the voice work that became his bread and butter in the late 1990s and 2000s — feels buoyant and conversational in sections but palpably remote in others. This might reflect the memory and stamina issues that have plagued Curry in the years since 2012, when he suffered a major stroke that paralyzed one side of his body. Or it might just be that there are roles, events, and parts of his career he’s just not that keen to revisit.

Curry’s understandable insistence on keeping his private life private hasn’t stopped some intriguing tidbits from getting out over the years. There’s his friendship with Freddie Mercury, for instance, who was among the boldfaced names who came to see “Rocky Horror” when it was performed in the small second-floor theater of London’s Royal Court; and his alleged disappointment at not getting a shot at playing Hannibal Lecter in “The Silence of the Lambs.” Neither of these, sadly, is mentioned in the book. On the other hand, his insistence that his relationships and flings are “none of your fu*king business” doesn’t stop him from insinuating that he and Miss Piggy had an affair while filming “Muppets: Treasure Island.” (“[O]ur dalliances never led to any tension with Kermit — I was clever about it.”)

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Which is not to say that “Vagabond” refuses to dish. Curry recalls assessing costars like Tom Cruise, who starred alongside him in “Legend” (“We never had any issues, but I cannot say I felt the appeal”) and Charlie Sheen, from “The Three Musketeers” (“Not the sharpest pencil in the drawer, Charlie”). He also gets in a few affable pokes at Ian McKellan, with whom he had a suitably competitive onstage relationship when they played Mozart and Salieri, respectively, in “Amadeus.” But Curry seems far more comfortable raving about his costars and directors, recounting his delight in working with the likes of Carol Burnett and Madeline Kahn — who did, in case you ever wondered, improvise the “flames on the side of my face” line in “Clue” — and the Muppets. (“I cannot overstate how much I enjoyed working with the Muppets.”)

Still, when “Vagabond” commits to a tale, it’s thorough: Curry makes a reader feel the claustrophobic spin-out brought on by 10 hours in a full-body cast (required to create the prosthetics he wore in “Legend”) and the mortified panic of ceding the upper hand to McKellan by snorting a few lines of cocaine before a performance. And while making very clear that he’s not about the method-acting life and in fact finds it pretty silly, he offers insight into how some of his memorable performances took shape. He struggled with finding the voice for Dr. Frank-N-Furter in the original theatrical run of “Rocky Horror,” cycling through German, American and generically European accents before realizing that the power-hungry mad scientist from a different planet required the performatively posh tones of someone trying to sound like the Queen of England. For the oily grifter Rooster Hannigan, he borrowed the mannerisms of a Broadway stagehand “who fidgeted a lot, in a very New Jersey way.”

Ultimately, “Vagabond” is a portrait of someone who has never stopped feeling lucky for the life he’s gotten to lead, as himself and as his characters. It’s hard for a reader not to wonder what Curry’s career might have looked like with a happier childhood, but it’s nothing he wants to dwell on. “I found work that allowed me to process the fear or isolation I felt as a child, and to put it to sleep. Everybody has a well of hurt and darkness somewhere. Many people never find the means to channel it.”

Read more

about celebrity memoirs