When discussing his work and its long conversation with the American story, Ken Burns often shares a version of a quote long attributed to Mark Twain. “History doesn’t repeat itself,” the maxim maintains, “but it rhymes.”

The filmmaker was careful to specify, when we chatted last summer about “The American Revolution,” that Twain is supposed to have said this. A little digging reveals that no one can find concrete proof that Twain, the father of American literature, said or wrote those words; it’s a captivating yarn, though, and one that’s not only caught on but held tight.

Besides, whether the quote originated with Twain or someone else doesn’t make its sentiment any less accurate.

“What the study of history tells you is that we’ve always been divided,” Burns explained, allowing that every time we’ve arrived at a breaking point, it feels new.

“I borrowed that because people have always said ‘history repeats itself’ – never. ‘There’s nothing new under the sun’ suggests that human nature doesn’t change,” Burns told me. “And what’s interesting about this project on the American Revolution is that you had a moment when human nature changed. Everybody, up to that point, had been a subject. Now, a few people on earth were these things called citizens. That’s a distinct moment.”

Burns is commonly known as America’s storyteller, which means that interviews during the cross-country tour that he embarked on earlier this year contain their own catchy scripts repeating in the lead-up to the debut of “The American Revolution.” Some veer into hyperbole, as when he describes “The American Revolution” as the most important event in world history after the birth of Christ.

But a little of that is understandable in this attention economy-driven age, defined in no small measure by a desire to forget or rewrite vast swaths of America’s history.

(Stephanie Berger) David Schmidt, Sarah Botstein and Ken Burns

Burns’ Seattle visit in July coincided with Congress’ vote, acting on a directive from Donald Trump and a false narrative, to claw back nearly $1.1 billion in federal funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The private, nonprofit corporation provided funding to National Public Radio and the Public Broadcasting Service, but the bulk of its money was funneled to local stations around the country and other grantees. All entities that benefited from CPB support received their final grant payments in September.

Even so, Burns and PBS are supporting teaching resources devoted to connecting students to the many accounts that make up our nation’s origin story. This is in addition to the voluminous effort spanning six nights and 12 hours that reasserts, among many truths, Burns’ dedication to exhuming the rocky facts buried underneath convenient mythmaking.

Burns and his co-directors, Sarah Botstein and David Schmidt, along with writer Geoffrey C. Ward, weave the myriad voices of those who witnessed America’s birth into a tapestry aglow with lofty ideals, hypocrisy, beauty and hideousness.

Throughout its episodes lurk excerpts of dialogue enumerating frustration about the state of the world that could be mistaken for modern complaints. These are drawn from official documents, primarily letters written by the men we call America’s founding fathers, along with thoughts from Enlightenment philosophers, ordinary colonists, Indigenous leaders, free African Americans, formerly enslaved people and many others.

Together, they persuasively built that riveting argument that the American Revolution was not a simple battle between American colonists and British redcoats. It was fought by a coalition of people from many nations, including the French and Spanish, as well as Black and Indigenous people who believed in the nascent country’s message of throwing off British rule to embrace self-government for and by its citizens.

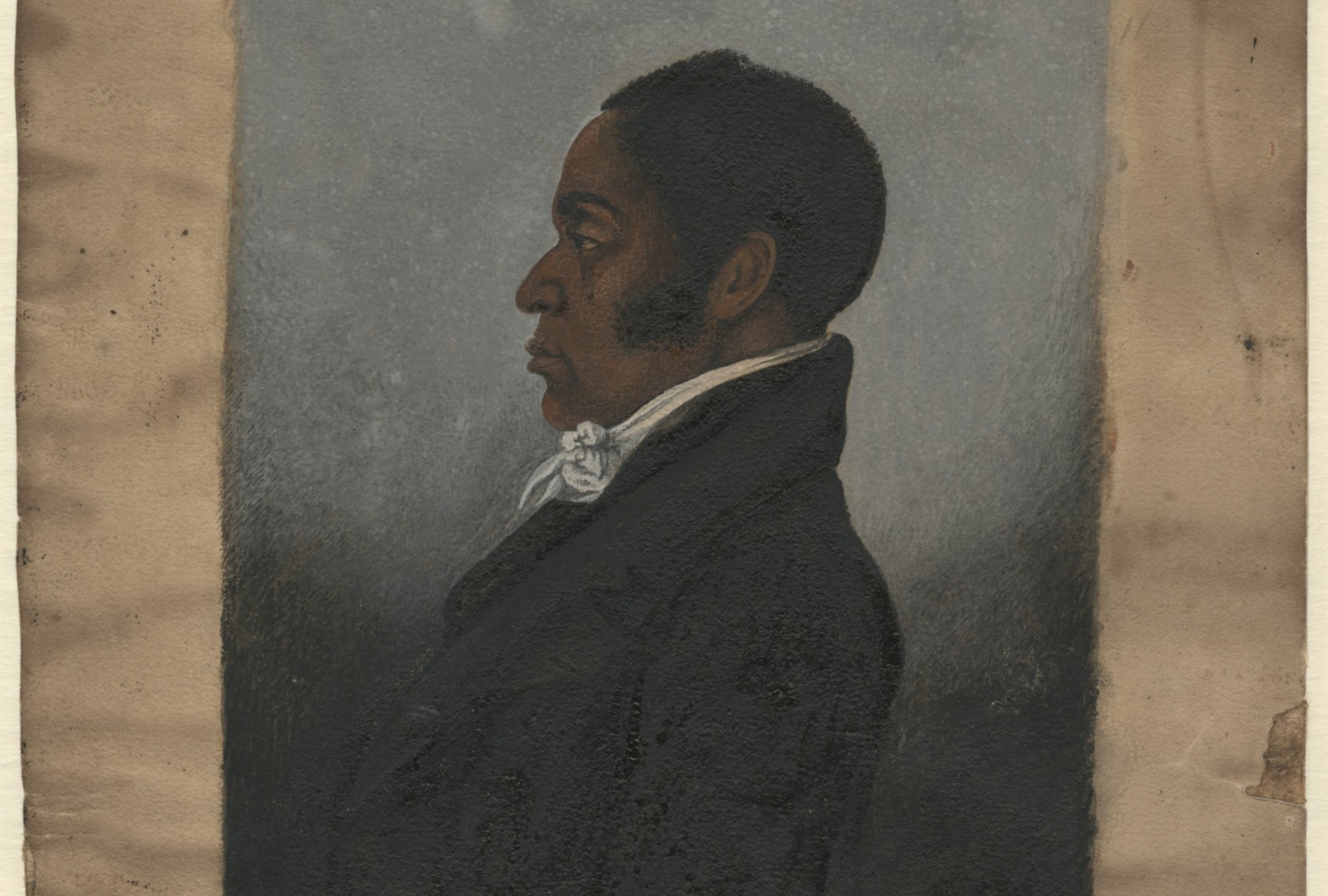

(Collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania) James Forten

And yet, determining who was worthy of citizenship spurred division and bloody conflict off the battlefield. Even at its founding, when our heralded Declaration of Independence insisted the equality of men to be a self-evident truth, the earliest European Americans, including George Washington and the document’s author, Thomas Jefferson, weren’t living up to that dictum.

The documentary meets Burns’ consistent standard of eye-opening storytelling, steadily marching through territory in American history that few, aside from academics and other experts, have traveled.

Members of the 13 colonies had to be persuaded to drop their resentments towards each other. Small towns were riven between people calling themselves Patriots and British Loyalists. Various experts describe the Revolution as a civil war more than once.

Bringing these viewpoints to life is a galaxy of performers contributing voiceovers, including Tom Hanks, Michael Greyeyes, Meryl Streep, Morgan Freeman, Ethan and Maya Hawke, and, in a metatextual wink, Paul Giamatti voicing John Adams, a role he played alongside fellow castmate Laura Linney in HBO’s 2008 miniseries, “John Adams.”

It is classic Burns, narrated by his longtime collaborator Peter Coyote, and similar in tone and solemnity to 1990’s “The Civil War” and 2007’s “The War,” while not quite matching the wrenching poignancy of 2017’s “The Vietnam War.” All that means is the documentary meets Burns’ consistent standard of eye-opening storytelling, steadily marching through territory in American history that few, aside from academics and other experts, have traveled.

We need your help to stay independent

When the current president of the United States is spearheading a whitewashing of American history with the goal of establishing a “patriotic” version, the series’ arrival seems especially timely. Burns doesn’t simply want to tell the most honest story about America’s beginnings, however, but one that shows how complicated, dangerous, grueling and ultimately inspiring that time was.

“Part of the dynamics of change and of the creation of the United States has to do with all of these different elements that are going on in these 13 colonies clinging to the Atlantic, to the eastern seaboard,” he said. “It is just fascinating. And to denude it, to sanitize it, to make it kind of a Madison Avenue thing — already our revolution, because it’s there are no photographs, there’s no newsreel, has been sort of sentimentalized. It’s easier to do that. If it’s just a painting, it can’t be that violent.”

(Yale University Art Gallery) The Declaration of Independence

With America’s 250th anniversary celebrations set to kick off in 2026, and when the nation is dangerously divided, Burns, Botstein and Schmidt’s work reminds us yet again that we have been to the brink before.

To the folks living through these times, Burns asserts, their era felt like the worst time ever. He can say that with plenty of conviction, having made exhaustive documentaries about the Civil War, the Great Depression and World War II. We’re living through America’s fourth great crisis, he said, preceded by those inflection points.

This is not supposed to offer comfort. “What the study of history tells you is that we’ve always been divided,” Burns explained, allowing that every time we’ve arrived at a breaking point, it feels new.

Want more from culture than just the latest trend? The Swell highlights art made to last.

Sign up here

Burns and his collaborators live in their work for years; research for “The American Revolution” began a decade ago, at the end of Barack Obama’s second term. He’s currently working on a project about the Reconstruction.

So when he says that knowing America has seen other bleak times becomes a bit reassuring, one might understand where he’s coming from.

“That’s where I think good stories help us. The binariness of our world right now . . . just doesn’t exist,” he said. “There are no edges, as Leonardo da Vinci would say. But I can’t think of a period that’s free of some sort of overwhelming division, and also a sense among people at the time that this is it, it’s all over.”

Nevertheless, it isn’t out of bounds to notice how uncannily relevant “The American Revolution” feels. Many of Burns’ works do, purely by happenstance. That is the nature of looking closely at what’s come before and telling its tale with clear vision.

“The American Revolution” premieres at 8 p.m. Sunday, November 16, and airs over six consecutive nights on PBS member stations.

Read more

about Ken Burns