For more than 48 hours, the 1959 Chordettes hit “Lollipop” has been stuck in my head. The song was part of a transitional scene in 1986’s “Stand By Me,” where the pop at the end is pantomimed by Corey Feldman and Jerry O’Connell, two of the film’s three surviving leads. It’s not the worst Rob Reiner earworm to have; no doubt someone else out there is plagued by “Big Bottom” or “Hell Hole,” or is simply hearing Bruno Kirby shout “Baby fish mouth! Baby fish mouth!” over and over. We all process grief in our own ways, and in the days following the murder of actor-director Rob Reiner and his wife, Michele Singer Reiner, I keep coming back to the music.

Reiner’s first film was 1982’s heavy-metal mockumentary “This Is Spinal Tap”; his last, released in September, was the long-awaited sequel, “Spinal Tap 2: The End Continues.” (A follow-up, “Spinal Tap at Stonehenge: The Final Finale,” was set to be released in 2026, but is now on hold.) In the most cosmically terrible way, this actually makes sense: “Spinal Tap” doesn’t define Reiner’s work, but it is the most undiluted example of his knack for blending music into antic-yet-poignant scenes like a supporting character.

(Michael Buckner/Variety via Getty Images) Rob Reiner at the “Spinal Tap II: The End Continues” premiere on September 09, 2025 in Los Angeles, California.

“Spinal Tap” debuted in 1984, which was a great year for movies about music only if your name was either Prince or Mozart. By contrast to “Purple Rain” and “Amadaeus,” Reiner’s first feature didn’t rank — “Spinal Tap,” a $2 million film with a box office of less than $4 million, was outperformed by both the Rick Springfield vehicle “Hard to Hold” and the Dolly Parton/Sylvester Stallone clunker “Rhinestone,” just edging past the Talking Heads concert film “Stop Making Sense.”

“Spinal Tap” doesn’t define Reiner’s work, but it is the most undiluted example of his knack for blending music into antic-yet-poignant scenes like a supporting character.

It wasn’t that people didn’t know that the movie was in theaters. Three years after the debut of MTV, rock and pop music’s influence was omnipresent, and a farce about over-the-hill rockers trying and failing to keep up with the times seemed likely to hit with a young, music-savvy audience. Instead, as Reiner would recall throughout the years, audiences gave it a resounding thumbs down: “People didn’t get it . . . [they] came up to me and they said ‘I don’t understand — why would you make a movie about a band nobody’s ever heard of?’” (Among these people: Ozzy Osbourne and, apocryphally, Oasis’s Liam Gallagher, whose brother Noel revealed that the singer didn’t know Tap was fictitious until he went to see them at Carnegie Hall in 2001.)

If it weren’t for the VCR, “Spinal Tap” might never have reached cult status and gone on to become a classic whose verisimilitude apparently brought a few actual rock stars to tears that were not of laughter. But eventually, the movie twigged with kids who were already bingeing Penelope Spheeris’s two-part documentary “The Decline of Western Civilization” and getting a solid primer on grubby British tomfoolery from “The Young Ones,” which MTV began airing in 1985. “Spinal Tap” was the logical next step, a film whose only misfire was that it was just too good at what it did right out of the gate.

Mockumentaries weren’t yet the staple of film and TV they would eventually become; Robert Altman’s “Nashville” and Albert Brooks’ “Real Life” were viewed more as metatext than as outright satire. Almost 25 years later, the New York’s Times’ John Leland recalled the lasting bruise of “Spinal Tap”’s initial reception: “[T]he film’s title has become a punch line waiting to reveal any subject as a joke, the more deadly serious the better.” (The New York Times itself, for the record, gave the movie two separate raves upon its release, with critic Vincent Canby calling it “one of the brightest, funniest American film parodies to come along since ‘Airplane!’”)

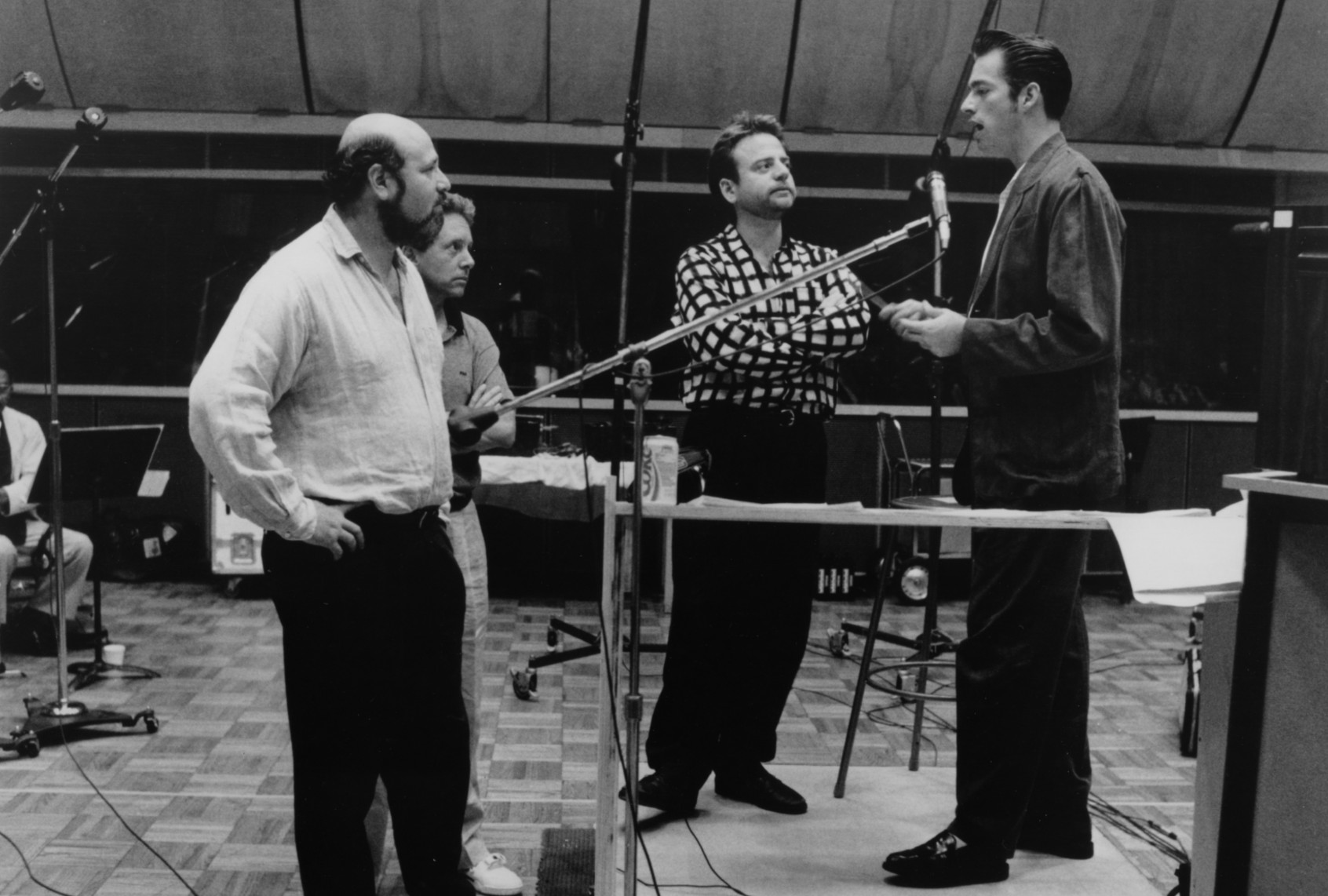

(Columbia Pictures/Getty Images) Jerry O’Connell, River Phoenix, Wil Wheaton and Corey Feldman in a scene from the film “Stand By Me,” 1986.

The movie bombed in theaters, but its soundtrack made the Billboard Hot 200, debuting at No. 131. This would become a pattern: The string of movies that followed “Spinal Tap” — 1986’s “Stand By Me,” 1987’s “The Princess Bride,” and 1989’s “When Harry Met Sally” — have little in common narratively, but bear the imprint of a director for whom story and music were equally important. “People wanted to know, ‘How do you know all this [about music]?’ [But] it was just the world I lived in,” Reiner recalled in a September 2025 appearance on Elvis Mitchell’s KCRW podcast, “The Treatment.”

Reiner was always determined to follow his father, comedy titan Carl Reiner, into show business. But he was already immersed in doo-wop and rock music and, in perhaps the quintessential Boomer origin story, took a short detour through San Francisco’s music-soaked Summer of Love first. His first official gig as a comedy writer was the envelope-pushing CBS variety show “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” which had a politically liberal slant and featured musical guests like The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, and Harry Belafonte; there, Reiner joined peers like Steve Martin in blending Borscht-Belt schtick with Haight-Ashbury headiness.

Want more from culture than just the latest trend? The Swell highlights art made to last.

Sign up here

Debuting at the start of the Vietnam War, the Smothers Brothers’ mix of social justice, political satire and psychedelia drew outrage from the network execs, sponsors, and — in a too-timely-to-ignore twist — even President Lyndon B. Johnson. (Johnson eventually came around, asserting that “It is part of the price of leadership of this great and free nation to be the target of clever satirists.”) Reiner’s stint on the show was brief (it was canceled in 1969), but it solidified an artistic voice that embraced the sincere absurdity of being human and the joy of being moved by music, by idealism, by love — and invited audiences to do the same.

“Stand By Me,” Reiner’s second feature, was adapted from the Stephen King short story “The Body.” Reiner changed the title so the movie sounded less like a horror feature, and decided on Ben E. King’s 1961 hit as the matching track for the film. He loved it, but more than that, he thought it spoke to the bittersweet bonds of preadolescence at the movie’s center, the constant teasing and squabbling and provoking that disappeared when they faced down a foe (hoodlum older brothers, leeches) as a united front. The four boys lived a life almost wholly devoid of parents and authority figures, where their connection to the world came largely via transistor radio. The film’s needle drops — Buddy Holly’s “Everyday,” The Silhouettes’ “Get a Job,” and my current earworm, “Lollipop” — seemed like dreamy sonic buffers easing the abrupt transition from child to teen.

Similarly, “When Harry Met Sally”’s spiffed-up standards, delivered in an anodyne croon by Harry Connick Jr., operate like a dapper Greek chorus that descends on the neurotic will-they-won’t-they chums, periodically affirming that the persistence of romantic hope isn’t as embarrassing as they think.

We need your help to stay independent

“It’s tricky, to satirize the very thing you love,” Reiner told Mitchell on “The Treatment.” He was talking about what makes “Spinal Tap” work, but could have been describing the core of his astonishing run of 1980s films, in which opposing forces — reality and fantasy, childhood and adulthood, friendship and enmity, timidity and bombast — all have their chance to shine. The “Spinal Tap” movies are famously scriptless; the dialogue is all improvised, with Reiner, as documentarian Marty DiBergi, the straight man silently “yes, and”-ing his costars to preposterous pinnacles. But that comedic generosity is visible in his other early films as well. Reiner frequently likened comic dialogue to jazz, where everyone knows what they’re doing; they spin into solos and then come back together in the pocket. “Someone lays down a rhythm track,” he told Mitchell, “and people fall right in.”

“When Harry Met Sally”‘s spiffed-up standards, delivered in an anodyne croon by Harry Connick Jr., operate like a dapper Greek chorus that descends on the neurotic will-they-won’t-they chums, periodically affirming that the persistence of romantic hope isn’t as embarrassing as they think.

People still are. In the days since his death, clips of Reiner keep surfacing as reminders of music’s meaning to his work. There he is in 1993, playing a director in the video for Reba McEntire’s 1993 hit “Does He Love You.” That’s him singing the Everly Brothers’ “Dream” on the set of “Spinal Tap 2” with Harry Shearer and Michael McKean. Here he is harmonizing gorgeously with “New Girl’s” Zooey Deschanel — Reiner memorably guest-starred on the show as Jess Day’s father — on the Christmas carol “Angels We Have Heard on High” and, as the same character, singing Tal Bachman’s romantic-comedy staple “She’s So High.” Meanwhile, Blue Öyster Cult dedicated a recent performance of “Don’t Fear the Reaper to the director, and, at their annual Hanukkah show at New York’s Bowery Ballroom, and Yo La Tengo broke into a shambling rendition of “Gimme Some Money,” the skiffle hit originally recorded by the fictional pre–”Spinal Tap” band The Thamesmen.

Rob Reiner was, I can only assume, constantly approached by fans blurting out “These go to 11!” and “I’ll have what she’s having,” yet never seemed to get tired of talking about his era-defining films as new generations found them. His life was taken horribly — but what a life. In that last interview with Mitchell, Reiner admitted that he thought of “Spinal Tap 2” as a romantic comedy rather than a mockumentary: Despite a fractious history, David St. Hubbins and Nigel Tufnel always came back together. “No matter what happens, whether there’s fights, there’s arguments, there’s disruptions in the relationship. They come back together because they’re bound together by the music.”

Read more

about rockumentaries