When I about 10 years old, I went through a phase where I believed that if I didn't say a specific and complex string of prayers every night, something terrible would happen to my mother — and it would be my fault. Within months, though, I no longer felt that urgency, and I soon forgot I'd ever even had it. I only remembered decades later, when the same thing came for my younger daughter. And what I didn't understand at first was that for her, it wasn't so simply resolved.

For my daughter, it started with what she called her "bad thoughts" and her terror that they meant she was a bad person. I took her to the social worker we'd seen as a family during my cancer treatment, but the sessions didn't seem to have any effect. Then she started watching "Scrubs" on Hulu with her big sister. She took a particular interest in Michael J. Fox's guest arc as a brilliant, troubled doctor hiding a secret mental disorder. "Do you know what OCD is?" she asked one evening at the dinner table. "Because I think that's what I have. Like the man on 'Scrubs.'" She was 11.

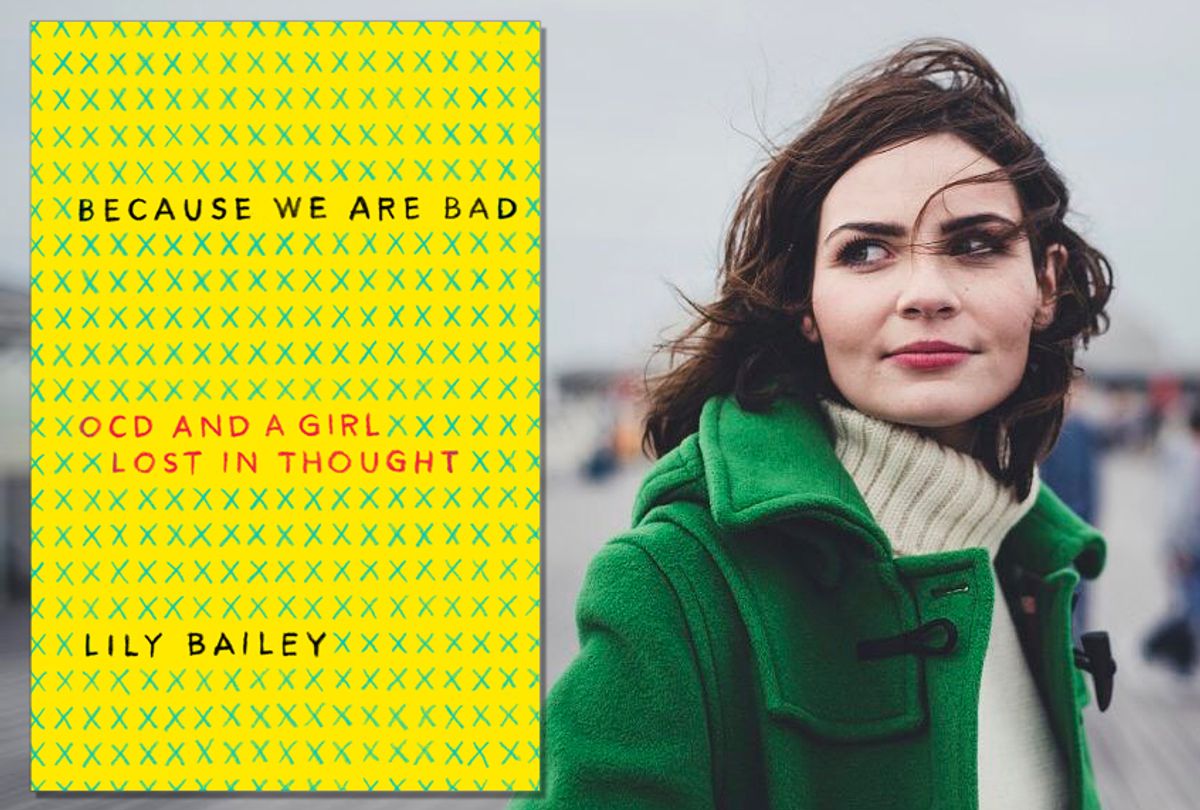

"I recognize that lightbulb moment," says author Lily Bailey. The 24-year-old English journalist's memoir of her own dance with the disorder, "Because We Are Bad: OCD and a Girl Lost In Thought," will be a bracingly familiar tale to those with firsthand experience with OCD and a much-needed educational tool for those who don't. Like my daughter, Bailey began manifesting symptoms as a child, which for her included list-making and intrusive thoughts but also manifested as a distinct voice in her mind. (And like me, Bailey's sister experienced some mild OCD symptoms she eventually outgrew.)

"When I saw my psychiatrist, she explained to me. It's about having obsessions and having compulsion," says Bailey. "Before I felt, am I just mad? Am I just nuts? Or am I a criminal? That [diagnosis] was very validating and reassuring, and then there was actually a lot of anger. That it did have a name, that it was so obvious. That I lived so long not knowing that's what it was. Then, there was real resistance. There was she, the voice in my head being like, 'No you don't. This is just us and how dare someone try put a label on it and say it's a medical condition?'"

I didn't understand any of this at first either. I thought OCD was Jack Nicholson in "As Good as It Gets" or Tony Shalhoub in "Monk." I didn't comprehend the importance of that "O" in OCD, the intense emotional suffering that intrusive thoughts impose on the person living with them. My daughter wasn't overly fastidious or concerned about germs. She was popular and friendly. And yes, it turns out she does have OCD, with a side of a mild tic disorder. There's no definitive known cause for the condition, though there seems to be a genetic component as well as environmental factors.

We were lucky. My daughter was eligible for a research trial and received an official diagnosis and started doing a treatment as cognitive behavioral therapy within a month of that dinnertime announcement.

"CBT is different from classic talking therapies," Bailey explains. "It's less about looking at the past and wondering why and how. One thing that we do in CBT for OCD is exposure therapy. The premise is that you expose yourself to the thing that you find fearful that triggers your obsessions, but without doing the compulsion. By practicing over time, that becomes a normal behavior, rather than instantly responding with the compulsion — which I definitely think CBT should be the first line of treatment response therapy always for people with OCD. CBT is very effective. I think it's something like 80 percent of people who have CBT will not necessarily recover, but they will really improve."

CBT was effective for Bailey, as it was for my daughter, though the first few months were intense and stressful. But once you have the toolkit in your arsenal and know how to use CBT, the ground shifts a bit, and you have to look to other long term strategies. Today, my daughter takes Prozac and she sees a therapist weekly to monitor her medication and mood. It is a big decision to opt for SSRIs for anyone, but especially a kid, and not a choice our family made lightly. It can also make a life-changing world of difference. And when I see my daughter undistracted and singing with her chorus or playing softball with her team, I'm exceedingly grateful.

For Bailey, it's been a similar path. After CBT, she says, "I then started doing a different type of talking therapy, with a therapist who had a more psychodynamic approach and was interested in talking about the past. We got in quite deep into feelings and difficult emotions, that kind of thing. It’s really, really helpful. I came off medication, but then when things got bad again, I went back on it."

The past few years have been an education for my family. They've also been, fortunately, a golden new age for awareness and for more accurate depictions of the condition in popular culture. On "Lady Dynamite," Maria Bamford, playing herself, does a standup routine in which she asks, "Have you ever had a creepy thought? Like, what if I licked a urinal? Oh god, I can't believe I just thought that. I should probably do a complicated dance step and clench my fists at odd intervals in case I fell over and accidentally licked it. That's a type of OCD!"

In John Green's lovely "Turtles All the Way Down," teenage Aza is a funny, clever girl whose OCD often puts her at odds with herself. "Please let me go,” she tells her own mind. “I’ll do anything. I’ll stand down." Green himself lives with the disorder, describing it as "'an invasive weed' inside his mind."

It's heartening that people living with OCD, like Bamford and Green, are creating new narratives to replace the "quirky neat freak" tropes that in the past gave us novelty items like OCD branded hand sanitizer. (Ugh.) Yet I get where some of those longstanding misconceptions come from. We're a culture that values neatness and cleanliness. In that light, OCD seems somehow like the "good" kind of mental disorder. Yet OCD often has zero to do with being tidy. It's just that you don't see a lot of "What If I'm Going to Do Something Terrible?" branded products.

"I think that the reason a lot of stereotypes exist comes from a place of ignorance. There's a whole aspect of it that isn't spoken about very openly," says Bailey. "I've had people say, 'Oh, do you really like everything that you see be neat? Are you really tidy?' I'm like, 'no, I have thoughts that I might abuse my sister,' and it's a real conversation ender."

In her book, Bailey eloquently explains what she's learned from her own therapists, that people with OCD actually tend to have very strong morals. That's part of why they're so disturbed by their intrusive thoughts. "They tend to be at the opposite end of scale to psychopaths, emotionally and relationally," she says, "[People with] narcissistic personality disorders or sociopathic disorders don't care if they're having those thoughts. It doesn't register at all with them. That's a really important distinction to make, and that really helped me."

What isn't necessarily helpful, Bailey says, is the well-intentioned impulse to equate mental issues with physical ones. "People are really passionate about making the comparison," she says. "Saying, 'If I had a broken leg, you would — dot dot dot. It's just the same.' I think that can sometimes be unhelpful to campaign so vehemently for mental health and physical health conditions to be seen as really equal in every way, because they're not. I think the nature of mental health is so complex and so wedded to stuff that isn't entirely physical. We don't really understand it fully."

OCD has no known permanent cure. My daughter has tough days and setbacks, and sometimes she has to take a teacher or instructor aside and tell them that. But Bailey says, encouragingly, "It's really important for people to know that help is out there and that mental health conditions are not a death sentence. The message needs to be somewhere between, 'This can get better' and 'This will be fixed.' I remember going to a support group and having someone come in who is really lovely, but her message was very much from her own place of, 'I've gotten better. My life is so brilliant, everything is going to be great. You can do it too!' In some ways that did really help me. But then in another way I remember thinking, 'I don't think that's ever going to be me, and if I can't do that, then is that a failure?'"

"People are always saying to me, 'Can you get better? Yes or no?' Well," she says, "some people do. And some people don’t."

She adds, "It doesn’t mean everyone has OCD, but everyone has weird unwanted thoughts, and some of the most caring and compassionate people are troubled by it. For me, just the knowledge of that was an amazing moment. That relief of realizing that you are not a terrible person. You don't have to live your life in this prison where you just think 'I'm bad, I'm bad, I'm bad.'"

Shares