Tracy Clark-Flory was, in many ways, the prototypical millennial feminist. During her early career years as a writer for Salon and later Jezebel, Clark-Flory carved out a name and a reliable beat as a curious, candid chronicler of modern sex culture. The Tracy I knew then was the Tracy who appeared in her frank, refreshingly non-judgmental columns, a woman who could write descriptively about a one night stand with a porn star or the realities of a "friends with benefits" arrangement.

The trolls, naturally, howled over her unapologetic daring. What they didn't seem to notice was a human being who was never flippant or cynical, who could also speak eloquently on the illness and eventual devastating loss of a parent. One who has kept her trademark sense of wonder through her new adventures of love, marriage and motherhood.

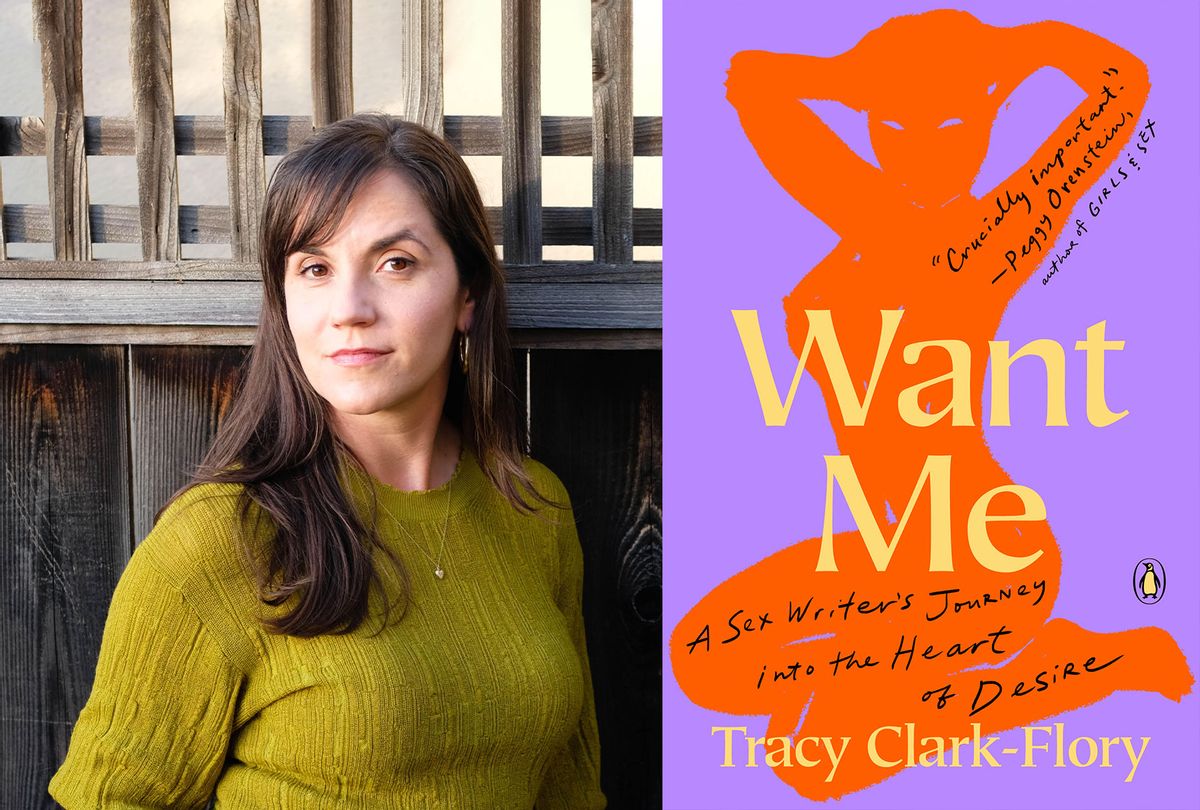

Now, in her debut memoir "Want Me," Clark-Flory widens her scope to look back on the person she was and has become, how she defined her sex life and her sex life defined her. It's rare for an author to approach her younger self with both unflinching candor and genuine self-compassion, but Clark-Flory does just that, as she grapples with the nuanced complexities of feminist ideals and the messiness of real, boots on the ground intimacy. I spoke to Tracy recently via phone about love, grief and faking orgasms.

The best place to start would probably be with the commenters, right? You've lived such a public life, and that has opened you up to a great deal of BS from trolls over the years.

It's actually improved dramatically. Back when I was first at Salon, that was really my initiation into writing about myself online and having anonymous strangers on the internet react to it in very violent and sometimes aggressive and hateful ways. Especially while writing for Broadsheet [Salon's female-centric former vertical], we had our resident anti-feminist trolls. At the time, I was in my early twenties and just having my writing published, period, was quite an experience. But then having my writing published and to have such vitriol in response was remarkable.

The way that I coped with it at the time was I tried to laugh about it. I would print out the very worst of the troll comments calling me the worst imaginable names, and I would post them on my fridge like, "Well, this is hilarious. There are these hateful people out there in the world who are so riled up about me making very simple, straightforward arguments about women being equal to men."

But there was also an undercurrent. As the years went on, I came to appreciate how not funny it was, and how much that harassment can have very real world implications. The conversation around online commenting and moderation has really changed since then, and so my experience right now is that I've learned to not read the comments. I have fully internalized that lesson and very rarely poke into any comment threads nowadays. I've also found that there's better moderation. But now of course there's Twitter, which is not so fun.

Do you still get lunatics coming at you?

Much less often. There have been times when I've written about figures in the manosphere, and them trying to engage with me on Twitter, that sort of thing. I ignore them and then it goes away. It's actually surprising how it seems to have really quieted down more recently. The thing that's surprising is, with Twitter, you can go viral and create backlash when you least expect it. I got so used to bracing for reaction writing about very controversial things, and then somehow it seems that when you least expect it, when you're not anticipating something to be controversial at all, that's when it blows up in your face.

When you talk in the book about putting the troll stuff on your refrigerator, it feels very consciously part of that larger story of you trying to figure out how to gird yourself from getting hurt. It's "Nothing can hurt me. Go ahead, bring it on."

It wasn't just the troll comments on the fridge, it was a general disposition or way carrying myself. Especially with my interactions with men. It wasn't just these anonymous men online that I was interacting with in this way. It was also the men that I interacted with in my personal life too. It was this protective outlook, a way of wearing my armor.

You talk about the dynamics of male porn stars expressing, "Wait, this isn't what I want; this is just what people expect of me." They don't feel a lot of agency. Similarly, your way of giving yourself agency was by really pushing back, by saying, "Nothing bothers me, nothing gets to me." And getting into some situations that in hindsight you can see were potentially dangerous. Do you think that's uncommon?

I don't think that's uncommon at all. I had in my early twenties this very defensive posture of, 'I'm down for whatever," which I realize now in retrospect is very protective. In my casual encounters with men, the possibility of assault, for example, did not feel front of mind. Yet because of the realities of being a woman in this world, it was present for me. I think that unconsciously I developed this defensive posture of basically, "I'm down for everything, so nothing can be done against my will." That was my way of protecting myself.

In writing this book and reading a lot of more contemporary feminist research, I've realized how much my experiences are really reflective of this neoliberal feminist mentality that emerged in the nineties that puts the emphasis on personal responsibility. It gives women permission to be sexual and avoid some of the usual judgments, as long as they do it with the impression of being in control and going after what they want. That is a terrible setup. It's a setup that, given the current state of things, given the fact of an incomplete sexual revolution, essentially asked women to perform, to act, to play the part of the sexually liberated.

It's a trope, but it's very real. The "cool girl" speech from "Gone Girl" touched a nerve because it's about women going along with something that's kind of crappy, that's supposedly "empowering."

It comes down to the fact that women often seek power through men, through being wanted by men, through being desired by them, through being married to them. The same thing happens with sexual desire. Very early on, girls learn that their sexuality is a liability. The developmental psychologist Deborah Tolman has this theory of the dilemma of desire, where young girls come up against their bodily feeling, their sexual feeling, and the real-world material dangers that are associated with their sexuality.

As a result, a lot of girls and women become disconnected from their own bodily experience, their own desires, their own wants. It's a very socially acceptable thing to reroute those desires through men, to be wanted by men. That happens in the realm of sex, but also in terms of navigating the world at large, that we hand over our desires to men, that we find satisfaction, that we find power, through being pleasing to men.

The thread that weaves through this whole book is you and the faked orgasm. That is not something that women admit, because it's considered such a failure. There are two aspects of that: There's you as a woman being settling for that, and there's that a lot of men don't seem to care.

I do often wonder about that. Looking back, there was no time when any man was like, "Was that real? Was that authentic?" Or, "Did that feel good?" There was literally never a time, except for maybe later on, in a longer term relationship where there was commitment and real emotional engagement. Aside from that, there was never a time where a man seemed to want to ask any questions about it at all. This does raise the question for me of how much awareness any of these men might have had about authenticity that was present, and whether it was easier, more pleasant, to buy it, to believe it.

There's a statistic you cite in the book about the percent of women who fake it and percent of men who think that a woman's had an orgasm.

Half of women report having faked it, and some research actually puts that number higher. There was a study that found that 95% of straight men reported usually or always having an orgasm when sexually intimate, compared to 65% of hetero women. That's a pretty substantial gap. When you look at straight women versus lesbian women, you see that there isn't the same phenomenon happening. There is something particular to the heterosexual dynamic here.

There was a study of thousands of young women in college who are having casual sexual encounters. The researchers concluded that if it was possible — and I love that they said "if it was possible" — to get young men to care more about women's pleasure, and for young women to feel more entitled to sexual pleasure, then that orgasm gap might be closed. I love it was, "if it was possible," as though it some great feat.

A lot of that does come from porn and the ubiquity of porn. Many of us as feminists struggle with, "What are we supposed to feel about porn?" I notice over the past several years, porn has gotten so much more brutal. Tracy, what's up with that?

It's really tricky. I do relate to that sense of, if you were to log into Pornhub, for example, and just go browsing around, what you would generally see would be very different from what you would see if you had logged in the early 2000s to vivid.com. At the same time, there have been studies that have analyzed these things and have said, "Oh no, porn is not getting rougher." I think often in these conversations, there is research, which is pretty scant, and then there's individual experiences like, "This seems so much more extreme."

When I started watching Tube sites in my twenties, my assumption was, "This is a very clear reflection of what straight men most want." That was my engagement with it. Over the years, writing about it, I've come to view it much more as an industry. You can take the example of Netflix. Netflix wants you to keep watching, Netflix wants to keep you engaged. It's not necessarily a pure reflection of what people want. I think that has an impact on the content that you see in porn.

I also think the advent of Tube sites, which totally decimated the industry, which totally decimated performers pay, has had a huge impact as well. I've talked to a lot of people in industry who reported how things have shifted, where performance have to move into more, quote unquote, extreme acts, much sooner in their careers that you have to do more for less. There's a lot that's happened to the industry through piracy that has changed the content.

It reminds me the performer you talk to in the book who says something like, "Anal is like a first date now." It feels like both men and women have to do more before they're ready, or if they're ever ready. Whether or not it feels good is almost irrelevant. It makes it harder for people to figure out what they really are into and what feels good.

There's this great example that the performer of Vex Ashley actually made in a scholarly article in the porn studies journal. She was saying, with Hollywood actions films, we might watch a crazy car chase, but then we have the real-world experience of driving around and seeing other human beings driving down the street and not jumping off the freeway. With sex, we might have our own personal individual experiences that fail to meet up to the fantasy realm. But because sex is so rarely talked about, because it's so shrouded in secrecy and taboo, we don't have the firsthand example of other people's experience to compared to our own.

The fantastical realm of porn is uniquely unchecked in the real world. The only thing that we can check it against is our own private experience.

I've always said that trying to learn about sex from watching porn is like trying to learn to drive from watching "The Fast and the Furious."

Our culture is totally ignorant around the realm of sexual fantasy. There's this real lack of appreciation and understanding of what sexual fantasies mean, what they don't mean, how they serve us. I think that they're often interpreted fairly literally. There's a real failure to appreciate the world of sexual fantasy is a magical place of pretend and illusion that can address some of our deepest fears and dreams.

You are now in a different stage in life. What do you want now for your life going forward into the next phase? What do you think is possible for women right now?

It's all been about this journey from that sense of "Want me," to more of a sense of, "What do I want?" And so moving towards a more embodied place of being in touch with my own desires, not just sexually, but broadly. There's a lot that happening with this book that speaks to what I want, which is being able to be a mom, being able to be in a married monogamous relationship, and also publish a book like this and to stand by this as this is part of who I am. To be that fully incorporated person who doesn't have to pick one category or the other, and doesn't have to live in with the fractured self, but can have a a more incorporated experience itself.

There's this rising generation of girls and boys coming up behind you, who are part of a different world. Do you think they have an easier time, the same time, a worse time navigating their sexuality in this world right now?

I think that in a lot of ways, things are better. The acceptance and around sexuality, the nuances around identity, the conversations that are happening right now are, without a doubt, major progress. The evolution around attitudes towards sex work, although slow, younger generations are so much further ahead in terms of figuring that stuff out than even my generation. And that's incredibly positive.

One thing that is concerning to me is the fact that this neoliberal feminist narrative that I mentioned has really pushed feminism away from this collective struggle into one of individualistic gain, a "lean in" style feminism tha in the realm of sexual empowerment is really discouraging.

I think about young women coming up and continuing to be encouraged to pursue sexual empowerment as though it were an individual job, as though, if you do not feel totally sexually empowered, it is your own fault as opposed to the cultural backdrop. One of the main struggles for me was coming up with that narrative of sexual empowerment. I believed that I could get it right on my own, as opposed to looking at the broader backdrop.

One of the greatest lessons from all of the time that I spent writing about sex at Salon, because I so often was interviewing individual people about their sex lives, was how much people keep hidden and how hungry people are for more of a sense of a collective engagement around these topics.

It's so easy to feel like, "It's just me." Any time I'm interviewing people about their sex lives, everyone's concerned that they're not normal. Everyone is so exceedingly normal in that sense. We're all so concerned that we're little weirdos, and we're all little weirdos. And how wonderful is that?

Shares