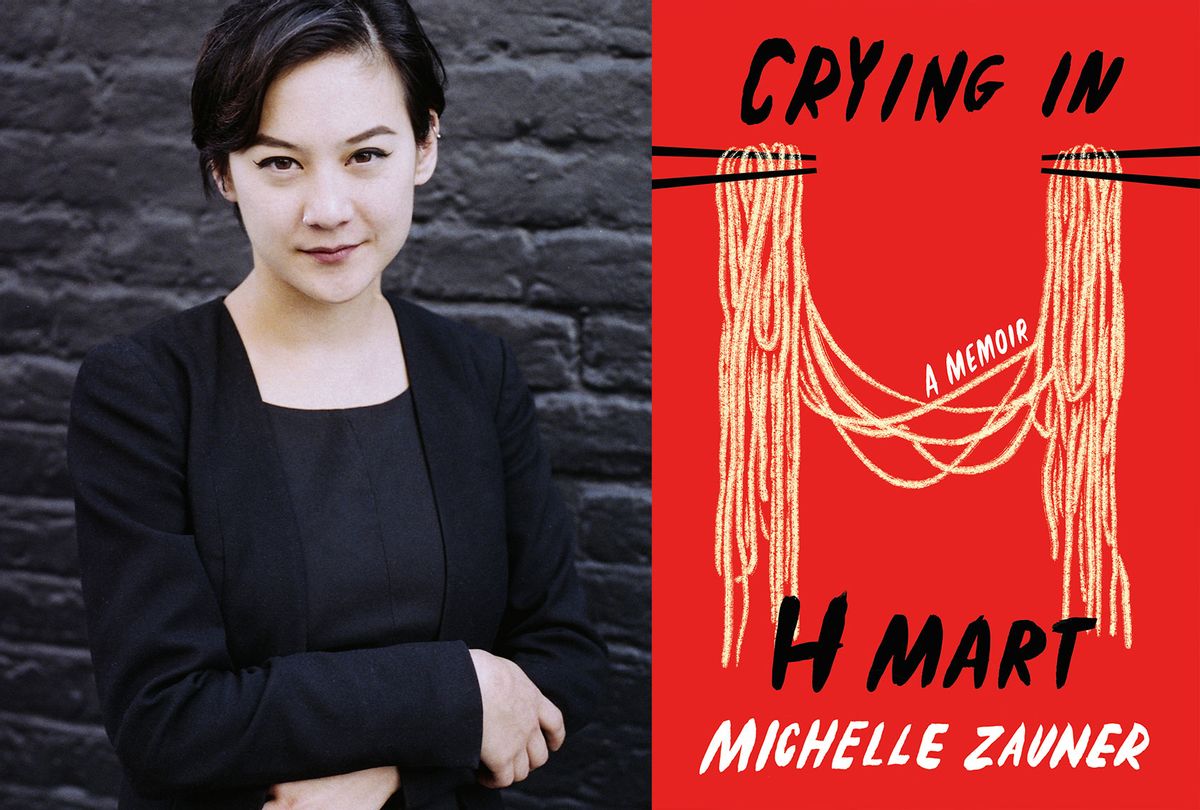

The genre of food memoir is notoriously white, with restaurateur Eddie Huang's "Fresh off the Boat" standing out for using Chinese cuisine to explore questions of Chinese-American identity and assimilation. But it's the specificity of Korean-ness that matters in Michelle Zauner's memoir, "Crying in H-Mart" (Knopf, April 20), which expands on her viral 2018 New Yorker essay of the same title. Even as the much-fêted film, "Minari," has opened conversations about the unique contours of the Korean-American experience, Zauner's intensely personal writing examines the role of food memories in the construction of selfhood when only one parent is Korean.

Exploring mixed-race identity, food culture, and maternal loss, Zauner's memoir opens with her explaining that she finds herself crying in H-Mart – the wildly successful Korean-American grocery chain that specializes in Asian foods – because it reminds her of her mother.

You'll likely find me crying by the banchan refrigerators, remembering the taste of my mom's soy-sauce eggs and cold radish soup. Or in the freezer section, holding a stack of dumpling skins, thinking of all the hours that Mom and I spent at the kitchen table folding minced pork and chives into the thin dough. Sobbing near the dry goods, asking myself, Am I even Korean anymore if there's no one left to all and ask myself which brand of seaweed we used to buy?

For Zauner, H-Mart is both mecca and memory palace, composed of cubby after cubby of a personal history evoked through taste, laying out a universal history of mothers and daughters evoked through the mundane rituals of meal-making. The result is a kind of literary bibimbap: so painfully delicious, it will make your eyes water.

But, it is also in H-Mart that she finds herself to be someone more than her mother's daughter — and more, too, than her musical identity as the solo indie artist known as Japanese Breakfast. She'd chosen this name for herself because "Japanese" was default for "Asian" when she was growing up in Eugene, Oregon. That name aptly condenses the primary collisions in her life: the ways others perceive her as a body and a being; and the intimate, life-affirming rituals she claims for herself. Both are lifetime projects.

Recently, Salon was able to chat with Zauner about her memoir.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Your memoir is so important because it lets Korean parents know, "Hey, it's okay if your kid wants to follow a creative path! It's not certain doom!" You're probably currently best known as a singer-songwriter, but did you start by envisioning yourself as a writer?

English was always my favorite subject in middle school and high school. I did quite well in those courses, and thought the most realistic path for me was as a journalist. Then, in high school, I had a kind of mental breakdown; I didn't want to go to school anymore. It felt pointless. It was around the same time that I became really interested in music. It was really important to my mom that I go to college; and when I did end up going, she kind of gave up a bit on the worrying — telling herself, you know, "She's in school, she's okay." At Bryn Mawr, I ended up taking creative writing classes with Daniel Torday and film classes with Homay King, both of whom ended up being extraordinary mentors. This became my way of being able to direct a short film and writing stories, and we called it "creative production." It seems incredibly impractical, but this is what I do with my life now. I was always interested in being a writer. Yet, at the time, it somehow seemed more unfeasible to be a writer than a musician.

Okay, I apologize for laughing but that's hilarious.

There's this thing where Asian parents force you to play an instrument at an early age, but god forbid you like it and want to pursue it professionally! But, as a kid, I never did choir, and didn't sing.

For Koreans, singing in church, singing in restaurants, singing in general is pretty common.

In Korea, we did norebang [karaoke] and things like that. But I didn't sing in church. My mom was the only one in the family that shirked religion. In retrospect, I think that makes my mom a courageous person. It kept her apart from the rest of the Korean community [in Eugene], which was already tremendously small, but she really didn't like being told what to think. In her way, she was a very individualist thinker. When my aunt got remarried, though, my mom made me learn this Korean song — a hymn, I think –and I remember being mortified because I used to think I had the worst voice in the world.

And here you are now, a famous indie singer. You write your own songs . . .

. . . I do!

How would you compare the two processes — writing songs, writing a book?

I think they're connected processes in that they draw from a similar pool of memories. It certainly took a much longer amount of time to write a book, and it was more of an analytical process. I feel like writing music is more intuitive. But, there are lots of references in the book to my music – shared titles and quoted lyrics, things like that. One of the things I put in "Jubilee" [her forthcoming album] was a line about fermentation and fermenting; and there's an entire chapter in the memoir about that. I really loved hiding Easter eggs like that in the pages.

The way you described yourself as a teen . . . you were a real handful! I really felt for your mom.

I think a lot of it was just having a really independent spirit, and feeling like I was being quashed by my mother's concerns and strictness. It was really confusing to have an immigrant parent from another culture to go up against. I was lashing out. I had all of this creative energy that I didn't know how to channel, and that she couldn't understand. But I also couldn't understand the way that she was. That was our major point of contention. I was just a tremendously sensitive kid and didn't know what to do with all those feelings. I calmed down a lot as soon as I left the house, honestly.

For the sake of my memoir-writing colleagues, I am compelled to ask: what literary influences played a role as you set about writing your book?

Ruth Reichl's "Tender at the Bone"; Nora Ephron's "Heartburn"; Chang-Rae Lee's "Native Speaker"; Joan Didion's "Year of Magical Thinking"; Alison Bechdel's "Fun Home"; Anthony Bourdain's "A Cook's Tour" . . . I read a lot of food memoirs, mother-daughter memoirs, and musician's memoirs in preparation to write my own.

In addition to tracing the arc of your relationship with your mother, your memoir might also be read as a document of the changing perception of Korea itself, corresponding with the rise of all things Korean — Korean food, K-drama, K-pop — in global popular culture.

In the book, a big question for me was "Where do I belong?" It's about staking out your own sense of belonging in the things that you create for yourself. I honestly feel that being "half" and not fully anything is a huge part of my identity; something that I feel very deeply is this place of unbelonging. Turning to the arts was a way to create a sort of home for myself. In writing this book, I discovered that I identify most strongly as artist, not as a Korean person or an American person.

How to do you see yourself and your art inside this expanded global frame?

We're in an interesting time. People are hungry for stories by marginalized voices and recognizing the universality in them. I hope to be always creating personal art.

Shares